Tesla’s Hot Summer Looks Like the Fracking Boom

Both share a revolutionary story, shaky profits and regular capital-raising. That didn’t end well for frackers.

by Liam DenningThe end of summer was like some Hollywood take on the end of the oil age. Except these things actually happened:

- Exxon Mobil Corp., Big Oil’s unofficial figurehead, was booted from the Dow Industrials after nearly a century in the index;

- Following a long decline, the energy sector finally became the smallest component in the S&P 500 for the first time ever (as my colleague Nathaniel Bullard tweeted here);

- Tesla Inc., Big Oil’s unofficial nemesis, surged past $400 billion in market value, a level last seen by Exxon in 2014 (its own market cap is currently at $155 billion, a level last seen by Tesla in … June).

So it’s all based on a true story. But it’s worth fleshing out the full story. Even in the energy transition, some things don’t change.

Exxon’s removal, heavy with symbolism, merely cut the Dow's energy weighting to more like the S&P 500’s (Chevron Corp. is the Dow’s sole remaining oil major). But Exxon's exit and energy's low status in the index both come down to a loss of faith.

Until recently, Exxon toughed out the oil crash with big spending; the proverbial zigging as others zagged, preparing for the next oil bounce. Covid-19 rather undercut that story, but it was a tough sell even before the pandemic. Climate change and peak oil demand have become mainstream topics of conversation. Perhaps more importantly, the past decade’s shale miracle did wonders for drivers, oil executives and “energy dominance” fantasies, but not for investors. It isn’t a coincidence the hit to Exxon’s credibility is rooted in the same thing that turned investors off the sector in general: an expensive pivot to shale.

Tesla, meanwhile, appears free from such constraints. Consider three numbers. In its latest quarterly results, the company reported its fourth net profit in a row, bringing total GAAP earnings for the trailing four quarters to $368 million. Meanwhile, sales of regulatory credits over the same period generated revenue of $1.05 billion. Such revenue essentially falls straight to the bottom line, so Tesla’s novel run in the black owes everything (and then some) to these subsidies. Now here’s the third number: $248 billion. That’s how much Tesla’s market cap rose in the year leading up to those results. It works out to 675 times the trailing GAAP profit.

Thus encouraged, Tesla did the natural thing: sold more stock. The $7.3 billion offloaded this year is more than all of Tesla’s prior offerings over the past decade put together. It also happens to be more than the entire U.S. exploration and production sector issued over the past three years.

I have argued for a long (so very long) time that Tesla’s valuation makes no sense but also that this very same thing should terrify rather than amuse oil executives. At the least, they should recognize the parallels with the phenomenon that disrupted their own business: shale.

Shale operators today are a “show me” story. Any E&P company with a hope of surviving now trumpets its commitment to generating real profits and paying them out. Having been burned so badly over the past decade, though, investors demand evidence of real change before they even think about buying back in.

But shale used to be what Tesla is today: A “tell me” story. Tell me all about your cool technological breakthroughs. Tell me how big the growth opportunity is. Tell me how an isolated example of this or that project represents the company’s performance overall. Tell me how all this spending will ultimately lead to huge profits and the perpetual motion of self-funding. Tell me and then sell me more stock so I can get in on this.

It’s worth remembering that the biggest year for equity issuance by the E&P sector wasn’t when oil averaged $100 or more — the years leading up to 2014 — but 2016, when oil plunged below $30. The narrative — of shale’s resilience, of oil’s inevitable rebound, of growth, of OPEC’s omnipotence — persuaded investors to look past the carnage of the oil crash and the copious red ink. In the absence of earnings, E&P stocks were borne aloft on higher multiples. Only in the past couple of years have investors seemed to wise up, responding to falling oil prices with falling multiples. In other words, they’re not buying the rebound story until they see hard (and thus far elusive) evidence of it.

Leaving aside whatever SoftBank Group Corp. may have been doing, Tesla’s recent price spike had everything to do with narratives both real and imagined. A stock split generated a frenzy despite the fact it makes no difference to intrinsic value. The important thing was that enough folks maybe thought there were maybe enough folks who believed someone would be gullible enough to think otherwise. Meanwhile, Tesla’s four consecutive profits, however miniscule or squishy, stoked expectations of entry to the S&P 500.

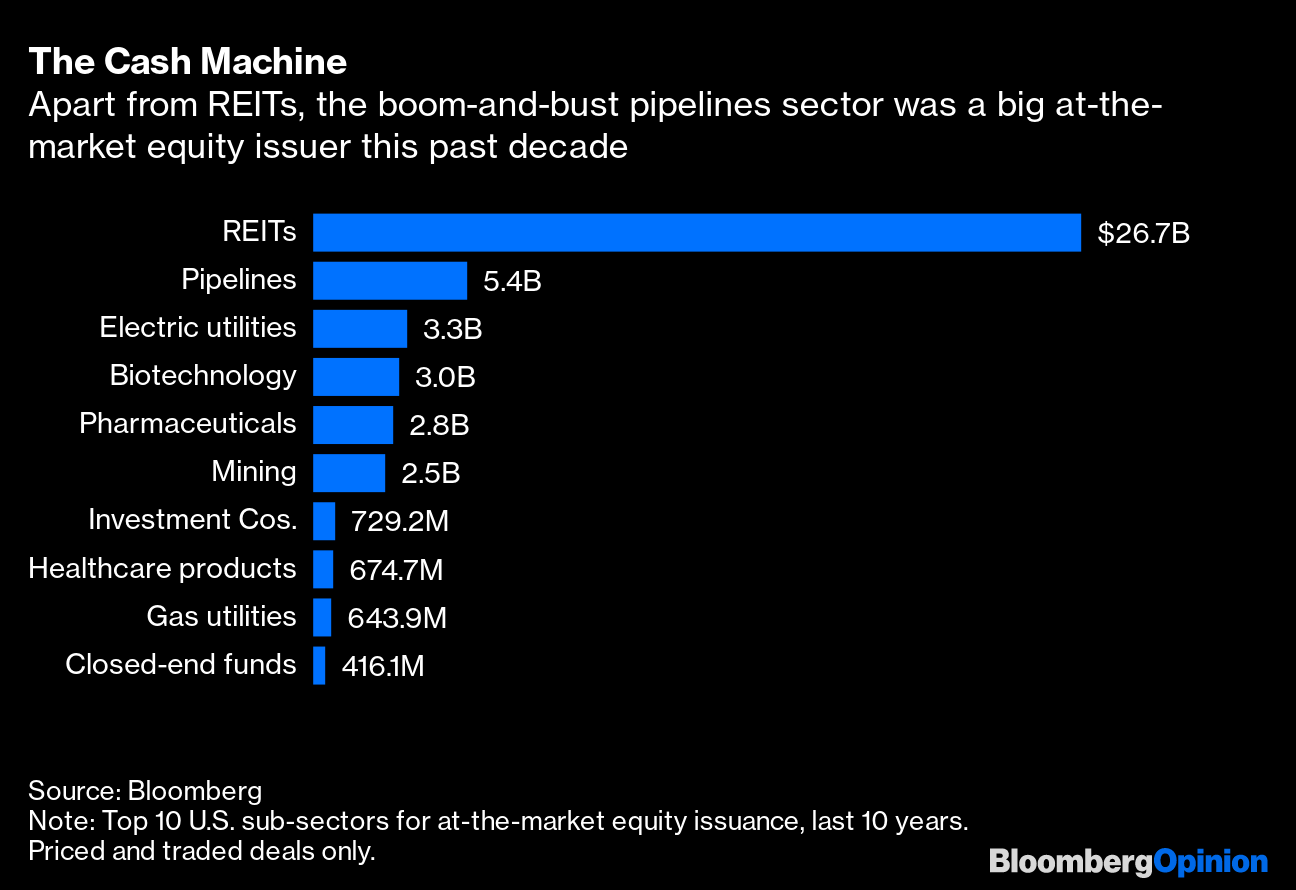

That the index took a pass disappointed such hopes. The inconvenient question left hanging is why an index would steer clear of a notionally profitable $400 billion-plus autos behemoth? That Tesla announced and executed a $5 billion at-the-market, or ATM, stock offering just ahead of the bad news should also jar with the narrative. Why is a company that listed a decade ago, regularly touts its bank balance, underspends on capex and has said for years it is on the cusp of self-funding raising $5 billion more — and via an ATM offering, more often the preserve of small, speculative companies in areas like biotech, to boot?

It’s worth noting that, apart from real-estate investment trusts, the biggest ATM issuers of the past decade were pipeline companies, a sector once beloved of retail investors and which was long on shale-inspired spending plans but woefully short on governance standards or sustainable business models. That ended badly.

Tesla’s important edge is that it sits on the right side of the climate-change challenge now posing a structural impediment to energy stocks. But it also displays the characteristics — a revolutionary story, weak governance, low or negative profits, regular resort to new capital — that enabled so many frackers to also upend the existing energy order while somehow failing to build sustainable, self-funding businesses. The scripts are wildly different, but when the tell-me base gives way to the show-me skeptics, the endings are similar.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

To contact the author of this story:

Liam Denning at ldenning1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story:

Mark Gongloff at mgongloff1@bloomberg.net