The Cross-Country Runner Fed Up With the NCAA’s Racist Exploitation

“I don’t feel comfortable continuing to support this disgustingly racist institution.”

by Jacob RosenbergLet our journalists help you make sense of the noise: Subscribe to the Mother Jones Daily newsletter and get a recap of news that matters.

We asked people who have quit since January 2020 how and why they did it. You can read more about the project and find every story here. Got your own quitting tale? Send us an email.

Andrew Cooper, 23

Position: Cross-country runner, Washington State University and the University of California, Berkeley

Started: August 2016

Quit: August 2020

Salary: $0

As told to Jacob Rosenberg

I actually haven’t gotten a lot of questions about my personal labor withholding. I’m a cross-country runner, you know? [Laughs]

I made the decision when we published the Players’ Tribune piece to opt out. I made my statement, right then and there. I made my announcement on social media.

You know, I had a few teammates who were frustrated that I didn’t talk to them first before making the decision, which is fair. I sent a long message to our team. I just said, you guys know how passionately I feel about these racial injustices, especially with everything happening. You know me personally. I don’t feel comfortable continuing to support this disgustingly racist institution, as a white male. I sent a long message to the team. Then I screenshotted that. I sent it to my coach. And he never responded. Honestly, I haven’t talked to him since, which is a shame. Because I love Bobby Lockhart. He’s a great coach. I believe that Bobby Lockhart will be one of the greatest coaches in cross country here in the next 10 to 15 years. But Bobby’s also got a job to protect. I don’t know that talking to me exactly fits in that description.

I’ve been running for the last 14 years of my life, essentially. Your sport really becomes a central component of your identity and existence. Everyone’s aware that it ends. I’ve heard other athletes describe it as grief, like something has died. You just feel so empty and lost when it’s gone. Winning in that sport fuels your existence as a college athlete. This feeling of being left behind is common. And that’s how I felt. I was completely unsure of how I would make money—well, I’m still pretty unsure of how I’m going to make money. I think so many college athletes struggle to see how their skills, their work ethic, their identities as athletes translate to life after sport.

This has always been my biggest frustration with this system of exploitation. Bottom line: Every single college athlete must sacrifice elements of their education to be college athletes. It fundamentally goes against the rhetoric the NCAA spits—we’re compensating you with an education, and that’s “priceless.” But you’re not even giving us a real education. Like, a real education. You can’t join clubs. You miss school. How can you say school is more important if you miss school for sports? Oftentimes you don’t have control or choice over what you study—particularly in football and basketball. Athletes who are wholly unprepared for college end up at prestigious universities.

I’m a graduate tutor. I’ve had to teach athletes how to write sentences. Like, I’ve had to teach athletes what commas are. I’ll say that Berkeley has the best tutoring system that exists in the country, because it’s external to the athletic department. To give you a little insight into how tutoring works: Everywhere else the tutors are paid by the athletic department. It’s ludicrous. If your job is on the line and someone’s boss is saying, “Look, this guy’s got to stay eligible, I don’t really care what you do,” and then you’re looking over and the kid’s not doing anything—you know you’re gonna just do the homework for them. The academic fraud that persisted at UNC, I think, is not far from the reality of many of these institutions. That’s the shame. That’s the disgusting shame that is not even remotely public. The reality is that every college athlete has to sacrifice their education.

There was actually a paper published today, an economics paper that has really confirmed what Dr. Derek Van Rheenen and I and many others have been yelling for a long time: College sports disproportionately exploits Black football and basketball players from predominantly low-income socioeconomic households, while benefiting predominantly white athletes from higher-income socioeconomic backgrounds. The racial divide in college sports can’t be ignored. But the lack of educational opportunities afforded to college athletes is, to me, the most sickening element of all of this.

So I made the decision to opt out in protest of the racial injustices of the country and specifically in protest of college sports, where predominantly young, Black football and basketball players are recruited and exploited for their athletic labor. That’s what my decision revolved around.

In 2016, when I was at Washington State, I had the opportunity to travel to San Francisco to participate in the Pac-12 Student-Athlete Advisory Committee. This was during the Black Lives Matter movement and Colin Kaepernick kneeling. We had really honest and powerful conversations around this topic. In all honesty, that was the first time I even learned that racism exists. I was very privileged to grow up in an affluent, suburban community. That privilege afforded me a phenomenal education and the opportunity to compete in such a leisurely activity at such a high level.

Following that conference, I was left shell-shocked by the realization that I was a white male benefiting tremendously from this privilege. I was completely clueless to the racial injustices of our country due to the whitewashed education I’d received, and I was asking my peers, “What can I do? What should I do?” And they just told me listen and use your platform of privilege to enact change. And I said, “OK, noted.”

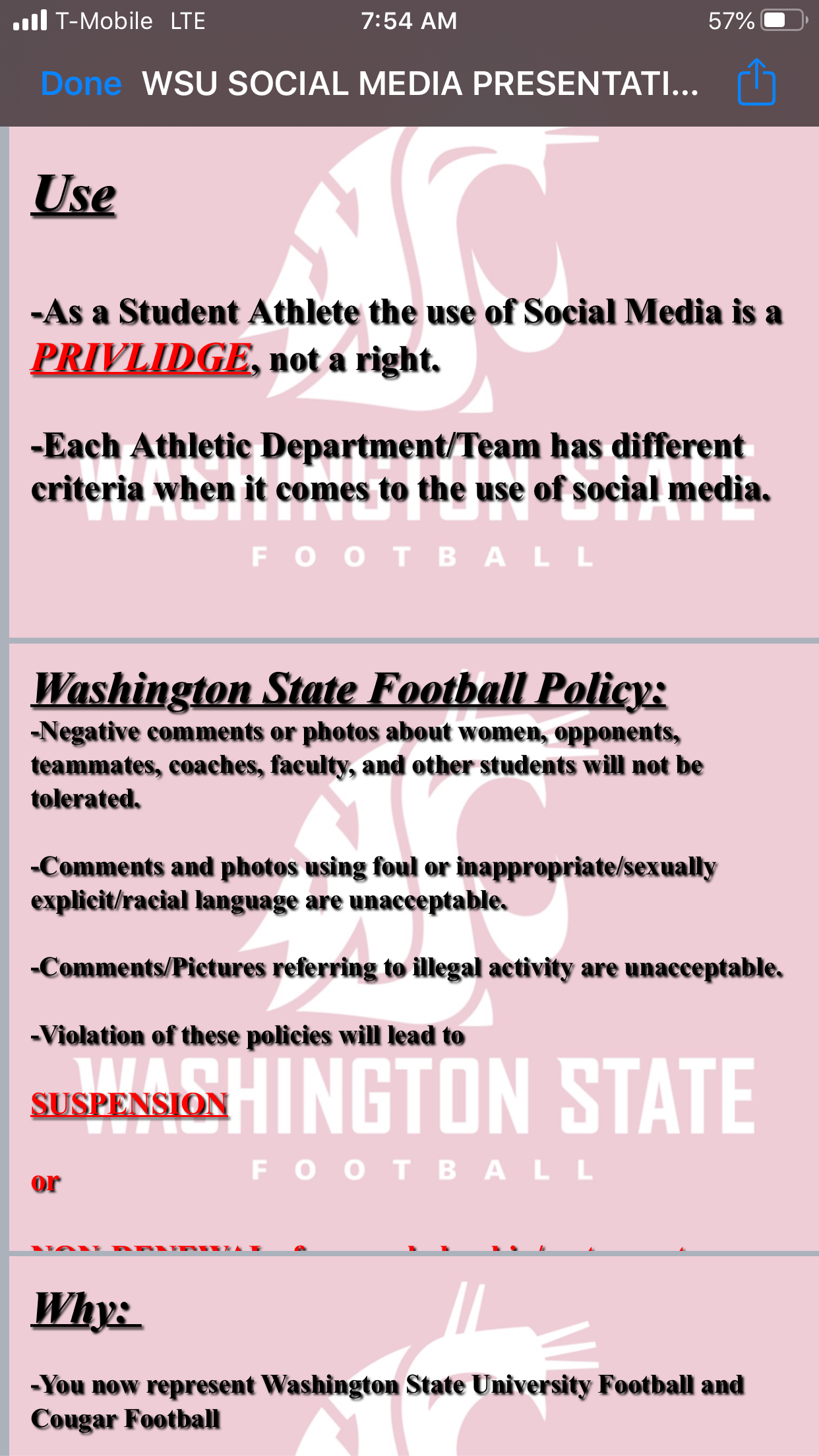

When I came back to campus, our university president, Kirk Schulz, tweeted something like “Going to the Pac-12 council meeting, anything you guys want me to talk about?” I went to my email, and I typed in his email address, and then I sent him an email essentially saying: “Hey, can you please discuss racism. I know on our campus specifically, people do not feel—people of color, students of color, Black students—don’t feel safe or comfortable at this predominantly white institution.” That was in part due to a Republican student group building a brick wall in the middle of campus and spray-painting “TRUMP” on it. White students just spit hateful messages at the rest of our community. And the president did nothing. He just said we can’t do anything because freedom of speech. Ironically, this same institution, when they sit athletes down and show them compliance sideshows, says social media use is a privilege not a right. And they even misspell “privilege.”

Anyway, after that we had a conversation. I pretty much told them what I think they should do. They should start surveying campus to understand where we’re at, where Black students are at, with how they feel about the efforts and partner with the University of Washington on their racial injustice and equity effort. They said great. And then I never followed up, and I don’t think he did anything. Talking to other students of color on campus and leaders of student groups, they told me that they had lots of meetings with him, and it just felt like he never listened. To me, it felt like he did really listen. And it seemed like he almost had a change of heart. It made me realize that was probably the first time a white student had said something like that to him. That’s when I really became aware of the power of white privilege, and then as I started learning more.

I became SAAC president after that at Washington State. I started to understand why this institution has been able to exploit our athletic labor for so long. It started to make sense and really come together. I applied to Berkeley and Stanford with the idea that I would write my thesis on the systemic inequities of college sports to better understand how we can address them. I was admitted to Berkeley. After, I was on the phone with one of my favorite professors at Washington State—Scott Jedlicka, who taught sport ethics course that was quite enlightening—and we were just talking about Northwestern and why the union drive failed. I started to suggest, “What if there was some sort of, you know, not a real union, but a fake union or a showing of solidarity.” Just the idea of athletes coming together to talk to each other seemed really powerful to me—standing up for something that they believed in.

Once I started studying labor law intently and working with other professors and just really just learning as much as I could from as many people as I could, it became abundantly clear just how flimsy and really antiquated this institution of amateurism is—and both how simple and how difficult it would be to dismantle. Simple in the sense that if you just got every player to realize, “Oh, we have all the power, we can just sit out, we can get whatever we want.” That’s it. Change happens that simply, as we saw when the Milwaukee Bucks chose to sit out. College athletes have that same power. But at the same time, there are a tremendous number of systemic inequities that enable the exploitation to continue and persist. That’s the hill we’re climbing.

At Cal, I was offered the opportunity to represent every athlete at the Pac-12 council meeting, or SALT, as they’ll call it—the Student Athlete Leadership Team. SALT representatives are chosen by their respective institutions. They’re the voices of college athletes in the actual decision-making process. At the Pac-12 council meeting, presidents of universities, athletic directors, faculty athletic representatives, and senior administrators convene to discuss all these issues. When I went for Washington State—in Phoenix, at this luxurious resort with waterslides and margaritas upon check-in—Kate Fagan was talking about Madison Holleran dying by suicide, and what it meant to her. All the athletes were practically crying, and I was looking around and saw a bunch of the athletic directors, and they were not actually paying attention. That’s when it really became apparent to me that this is not changing from within.

When I got an offer to go to SALT for Cal, this came from Bobby Thompson, who is the director of student–athlete development. Later he called me into his office. He said, “Yeah, the leadership team decided not to send you.” This was their reasoning: They had sent a hammer thrower previously—they didn’t want to, quote–unquote, send another track athlete. He then told me, “They have never even cared who I chose.” I was like, “Well, who made this decision?” He said the SALT leadership team—which is the athletic director, university president, and others. So, it became clear to me that the athletic director, Jim Knowlton, essentially made the decision to veto my spot.

I wasn’t even surprised that it happened. Jim Knowlton knows who I am. He knows where I stand on these issues. I’ve been in these meetings with him. He knows that I will say the truth.

On July 1, I got a text intro to Valentino Daltoso. I got on a call with Val and Jake Cuhran, and they told me they were frustrated with how COVID was being handled on their campus and other campuses and they wanted to release a statement in the Players’ Tribune within a few days calling for change. That day I saw a bunch of tweets from football players saying we deserve to get paid, essentially. I told Daltso and Cuhran, look, you’ve got three distinct issues here. You have COVID. You have the racial injustices. And you have economic injustices. The solution to COVID is for the government to act appropriately. The solution to the racial injustices is to be as loud as possible. The solution to the economic injustices is to organize athletes behind a work stoppage. I think we made that pretty clear in our demands. I never made any decisions throughout this whole process. It was always the football players. There wasn’t ever a leader.

Two or three days later, we had a Zoom meeting with two to three leaders from every school, just to talk about how we’re feeling about everything. We had like 35 people on it. And it was probably the most powerful Zoom of this entire movement because everyone felt the same way about—I don’t want to say issues because there are so many issues—but everyone felt voiceless and felt that something needed to change.

I presented to them essentially what I’ve been working on for the last year. I made the PowerPoint in like 15 minutes, essentially saying: Here’s the historical context of how the NCAA has been exploiting your athletic labor through amateurism; here are the systemic inequities that have been preventing us from obtaining these economic rights; here’s what I think the solution is. And then we just started organizing. There’s no doubt in my mind—that was a historical Zoom call in and of itself. That Zoom alone was already further than anyone had ever gotten.

I would have liked to known what my last race of college would have been. I think I ended up going out on a 1,500. I’m a distance runner, so I shouldn’t even be running 1,500s. Yeah, I think I went out finishing last place in a 1,500. It was the day after I broke up with my girlfriend. I didn’t anticipate that being my last race ever. It just wasn’t an important race to begin with. But it was kind of like, that’s it.

References

- Cooper ran at Washington State University for two years. In 2019, he ran for the University of California, Berkeley, where he is now finishing his master’s degree.

- On August 2, the Players’ Tribune published #WeAreUnited, a list of demands from hundreds of Pac-12 athletes who’d been galvanized by the NCAA’s handling of the coronavirus pandemic to more thoroughly oppose the ways in which “NCAA sports exploit college athletes physically, economically and academically, and also disproportionately harm Black college athletes.” Athletes demanded to be paid, to form a union, and to end racial injustice, among other things. Cooper was a signee and involved in planning the letter.

- For years, athletes at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill were steered by academic advisers to classes that required little work beyond the completion of a single paper at the end of the semester. In 2014, academic adviser Mary Willingham published research—which the university has disputed—saying that many athletes could not read or write beyond an eighth-grade level. Willingham resigned, sued the university for creating a hostile work environment, and settled for over $300,000. The NCAA did not punish UNC, saying that because the “paper classes” were open to all, and not just athletes, the scandal was an academic one over which the governing body did not have jurisdiction.

- The NCAA has Student-Athlete Advisory Committees at multiple levels: campus, conference, and national. These allow for students to “have a voice” on rules and regulations. But they do not have authority on protocols for athletes.

- In 2014, the Northwestern football team attempted to unionize. Led by starting quarterback and star Kain Colter and backed by the United Steelworkers, players signed union authorization cards. Ultimately, their bid to unionize was rejected by the National Labor Relations Board, which punted on the fundamental question of whether college athletes should be considered employee.

- Fagan wrote the book What Made Maddie Run, which told the story of college runner [Madison Holleran](http://www.espn.com/espn/feature/story/_/id/12833146/instagram-account-university-pennsylvania-runner-showed-only-part-story). Holleran committed suicide at the age of 19.

- In a statement, a University of California, Berkeley, spokesperson called this a “misunderstanding”: “To the best of our knowledge, no offer to attend a Pac-12 SALT conference was rescinded to Andrew or any other student-athlete.” Cooper disputes this. He told Mother Jones he was disinvited in person. Afterward, when he asked for email confirmation, he was refused. Cooper also shared with Mother Jones text messages showing administrators asking him to attend SALT before the invitation was rescinded.

- Daltoso and Cuhran were leaders of the #WeAreUnited campaign and both football players for the University of California, Berkeley.