Volodymyr Dianchenko

Private data gone public: Razer leaks 100,000+ gamers’ personal info

No need to breach any systems when the vendor gives the data away for free.

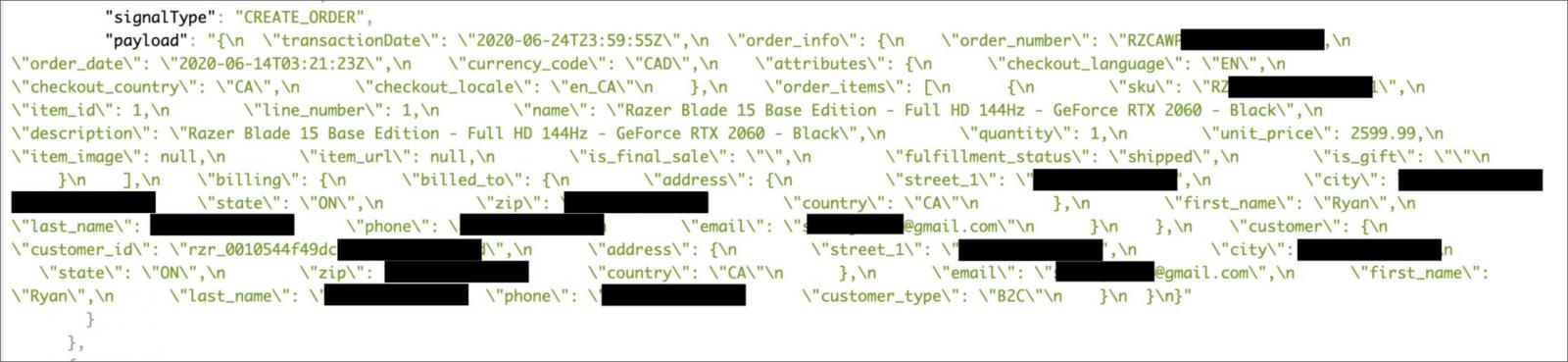

by Jim SalterIn August, security researcher Volodymyr Diachenko discovered a misconfigured Elasticsearch cluster, owned by gaming hardware vendor Razer, exposing customers' PII (Personal Identifiable Information).

The cluster contained records of customer orders and included information such as item purchased, customer email, customer (physical) address, phone number, and so forth—basically, everything you'd expect to see from a credit card transaction, although not the credit card numbers themselves. The Elasticseach cluster was not only exposed to the public, it was indexed by public search engines.

Diachenko reported the misconfigured cluster—which contained roughly 100,000 users' data—to Razer immediately, but the report bounced from support rep to support rep for over three weeks before being fixed.

Razer offered the following public statement concerning the leak:

We were made aware by Mr. Volodymyr of a server misconfiguration that potentially exposed order details, customer and shipping information. No other sensitive data such as credit card numbers or passwords was exposed.

The server misconfiguration has been fixed on 9 Sept, prior to the lapse being made public.

We would like to thank you, sincerely apologize for the lapse and have taken all necessary steps to fix the issue as well as conduct a thorough review of our IT security and systems. We remain committed to ensure the digital safety and security of all our customers.

We also reached out to Razer for comment. Shortly after this article published, a Razer representative confirmed the already published statement, and added that concerned customers may send questions to DPO@razer.com.

Razer and the cloud

Razer

One of the things Razer is well-known for—aside from their hardware itself—is requiring a cloud login for just about anything related to that hardware. The company offers a unified configuration program, Synapse, which uses one interface to control all of a user's Razer gear.

Until last year, Synapse would not function—and users could not configure their Razer gear, for example change mouse resolution or keyboard backlighting—without logging in to a cloud account. Current versions of Synapse allow locally stored profiles for off-Internet use and what the company refers to as "Guest mode" to bypass the cloud login.

Many gamers are annoyed by the insistence on a cloud account for hardware configuration that doesn't seem to really be enhanced by its presence. Their pique is understandable, because the pervasive cloud functionality comes with cloud vulnerabilities. Over the last year, Razer awarded a single HackerOne user, s3cr3tsdn, 28 separate bounties.

We applaud Razer for offering and paying bug bounties, of course, but it's difficult to forget that those vulnerabilities wouldn't have been there (and globally exploitable), if Razer hadn't tied their device functionality so thoroughly to the cloud in the first place.

Why leaks like this matter

It's easy to respond dismissively to data leaks like this. The information exposed by Razer's misconfigured Elastisearch cluster is private—but unlike similar data exposed in the Ashley Madison breach five years ago, the purchases involved are probably not going to end anyone's marriage. There are no passwords in the transaction data leaked, either.

But leaks like this do matter. Attackers can and do use data like that leaked here to heighten the effectiveness of phishing scams. Armed with accurate details of customers' recent orders and physical and email addresses, attackers have a good shot at impersonating Razer employees and social engineering those customers into giving up passwords and/or credit card details.

In addition to the usual email phishing scenario—a message that looks like official communication from Razer, along with a link to a fake login page—attackers might cherry-pick the leaked database for high-value transactions and call those customers by phone. "Hello, $your_name, I'm calling from Razer. You ordered a Razer Blade 15 Base Edition at $2,599.99 on $order_date..." is an effective lead-in to fraudulently getting the customer's actual credit card number on the same call.

Leaks and breaches aren't going away

Identity Theft Resource Center

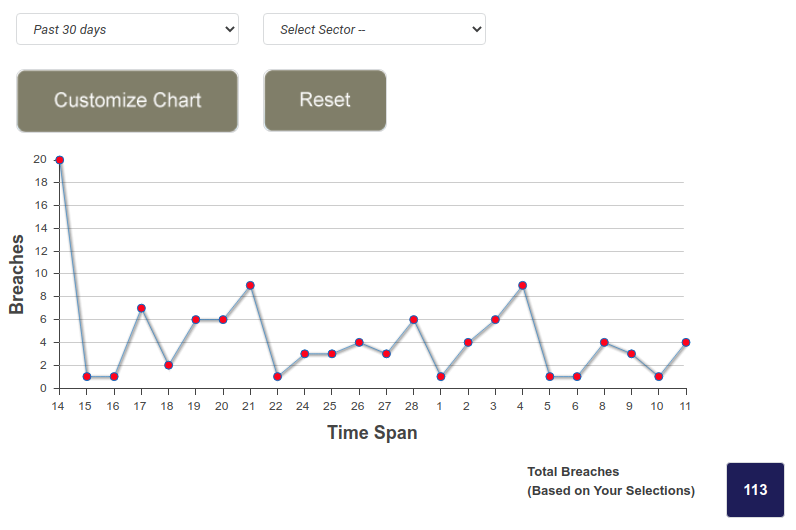

According to the Identity Theft Resource Center, publicly reported data breaches and leaks are down thirty-three percent so far, year over year. (IDTRC somewhat misleadingly classifies leaks like Razer's as breaches "caused by human or system error.") This sounds like good news—until you realize that still means several breaches per day, every day.

While the number of breaches is down this year—most likely, according to IDTRC, due to security hyper-vigilance by companies suddenly faced with remote work needs at unprecedented scale—the number of scams are not. Attackers reuse breached or leaked data for semi-targeted phishing and credential stuffing attacks for years after the actual compromise.

Minimizing your threat profile

As a consumer, there is unfortunately little you can do about companies losing control of your data once they have it. Instead, you should focus on minimizing how much of your data companies have in the first place— for example, no one company should have a password that can be used with your name or email address to log in to an account at another company. You might also strongly consider whether you really need to create new, cloud-based accounts containing personally identifiable information in the first place.

Finally, be aware of how phishing and social engineering attacks work and how to guard against them. Avoid clicking links in email, particularly links that demand that you log in. Be aware of where those links go—most email clients, whether programs or Web-based, will allow you to see where a URL goes by hovering over it without clicking. Similarly, keep an eye on the address bar in your browser—a login page to MyFictitiousBank, however legitimate-seeming, is bad news if the URL in the address bar is DougsDogWashing.biz.

Listing image by Jim Salter