There's No Easy Fix to OPEC's Whack-A-Mole Problem

The oil cartel’s 60th anniversary is marred not only by Covid, but a failure to keep its diverse members disciplined in meeting their output targets.

by Julian LeeThe Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries turns 60 tomorrow, and the oil producer group is putting a brave face on its Covid-curtailed Diamond Jubilee. But rifts within the cartel are resurfacing as de facto leader Saudi Arabia struggles to maintain discipline among members itching to pump more crude.

The birthday celebrations, due to be held in Baghdad’s Al-Shaab Hall where OPEC came into being, have been postponed as a result of the coronavirus pandemic. That may be a blessing as the OPEC family gathering would have been “a lot more like the Simpsons and a lot less like the Waltons,” to misquote former U.S. President George H. W. Bush.

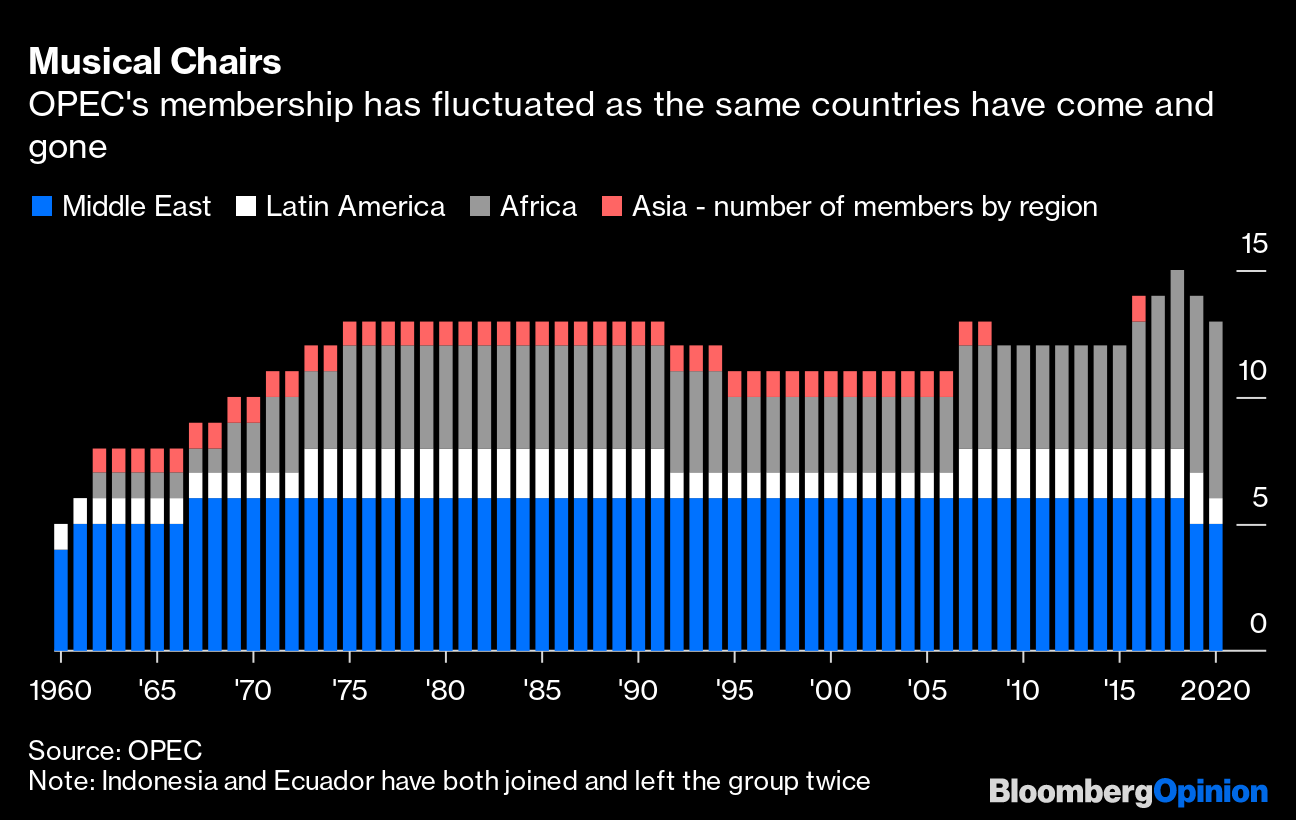

Rifts have always existed among a membership that for most of the group’s life has ranged between 12 and 15 very different countries, whose only unifying characteristic has been an economic over-dependence on oil exports.

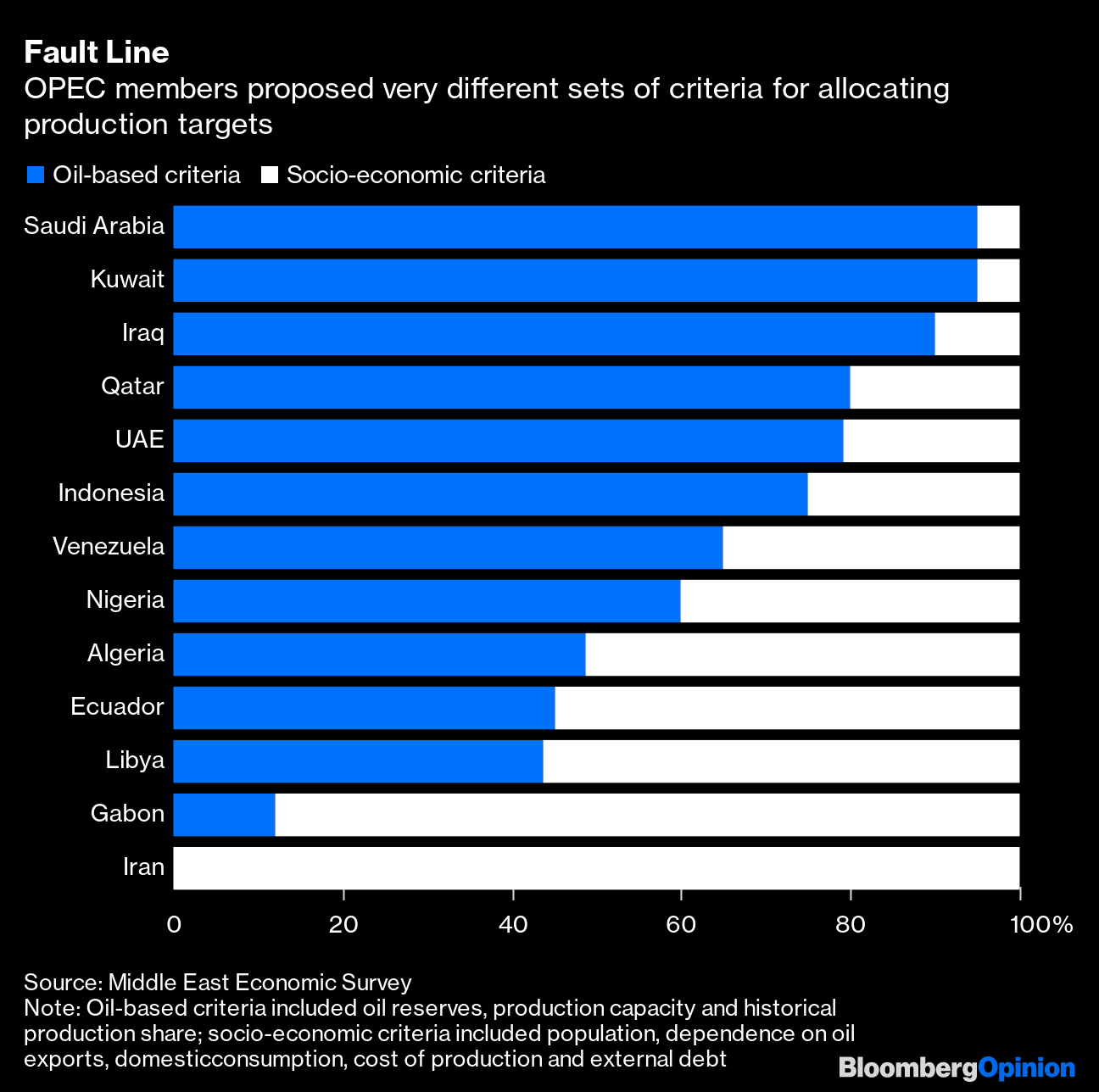

The differences at the heart of OPEC have never been more obvious than they were in the mid-1980s, when it embarked on an ill-fated attempt to create a rules-based mechanism for allocating oil production targets.

Members submitted preferred criteria for setting quotas, along with their suggestions for weighting them. Not surprisingly, the Arabian countries of the Persian Gulf, with tiny populations and huge amounts of crude, favored criteria based on their wealth of oil reserves. By contrast, countries with large populations and limited oil reserves favored socio-economic considerations, such as population size or the level of external debt.

The whole initiative was eventually allowed to wither away, having done little more than expose the deep fault line that cut right through the group.

That existential schism is the backdrop for OPEC’s perennial problem: Getting members to stick to the production targets they agree to. The cartel has never found an effective way to overcome this free-rider problem.

The Arabian Peninsula’s high reserves/low population countries have, in general, been much better at sticking to their output targets than the rest. The recent exception being Iraq, which was exempt from quotas from 1990 to 2017 due to war, sanctions and the need to rebuild its shattered economy.

Recently, it looked as though Saudi Arabia’s new oil minister Prince Abdulaziz Bin Salman had hit on a solution. Rather than turning a blind eye to cheating and shouldering a disproportionate share of the burden of balancing supply and demand, he has publicly shamed the “cheats” and demanded they make up for their initial failures to cut as much as they had promised.

It was never going to be easy to overturn a situation that had persisted for decades, yet the prince has been nothing if not persistent and his determination is bearing fruit.

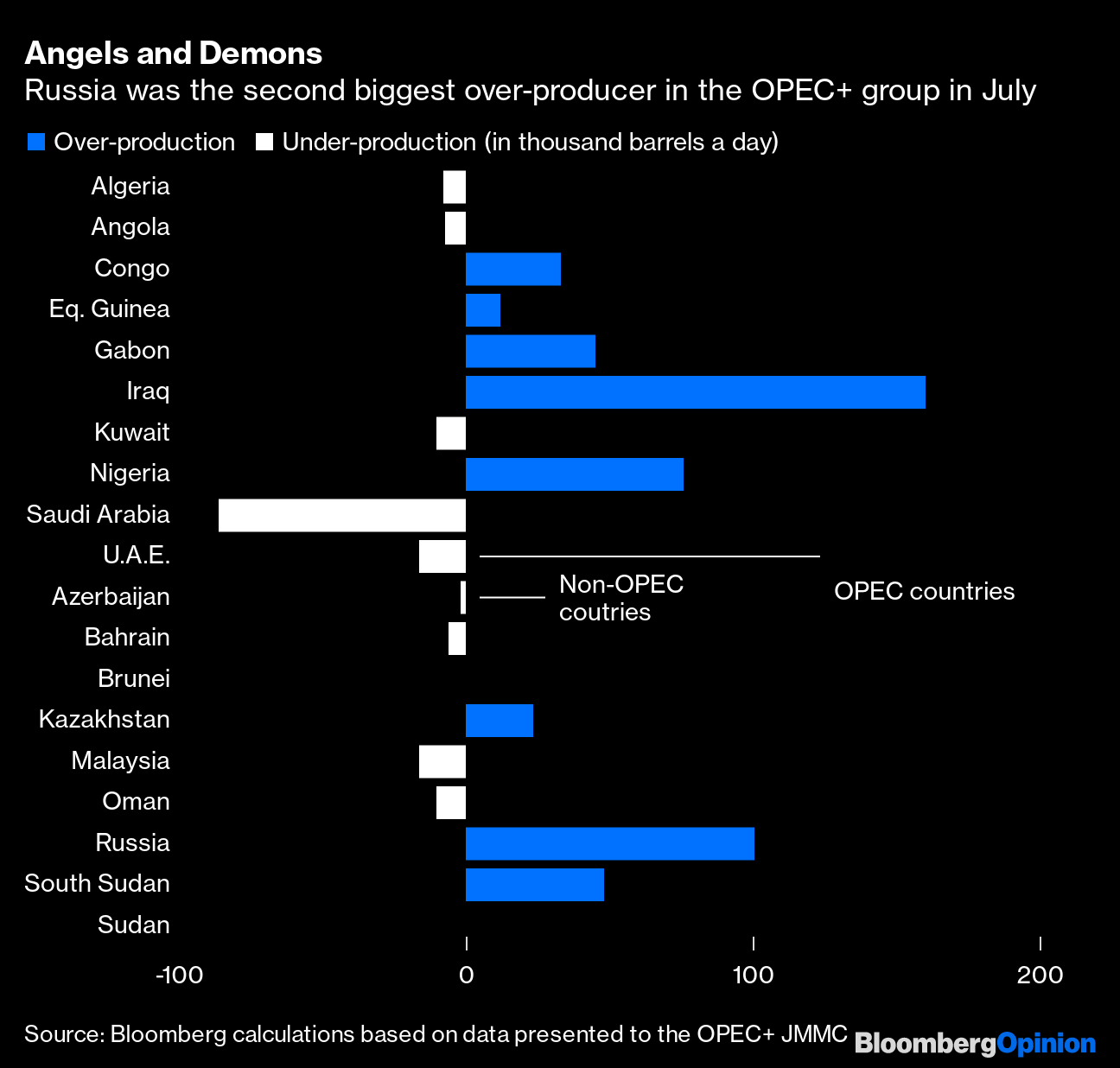

But it’s turning into a frustrating game of Whack-A-Mole. No sooner has one cheat been brought to book than another pops up. The two biggest culprits, Iraq and Nigeria, have both promised deeper cuts and even appear to be trying to implement them. But that’s highlighted the shortcomings of others, notably Russia, the non-OPEC counterweight to Saudi Arabia in the enlarged almost-four-year-old OPEC+ alliance so crucial to making any difference in a pandemic-plagued world.

Russia has implemented about 95% of the output cut it pledged in April, according to figures presented to the OPEC+ group’s Joint Ministerial Monitoring Committee (JMMC). That’s a lot better than during the alliance’s first agreement that ran from the start of 2017 until the end of March. But its production is still about 100,000 barrels a day above its target, making it the second-biggest over-producer in July in volume terms.

And yet no one, not even ABS as the Saudi oil minister is commonly known, is calling the country out.

Why has Russia been given a free pass? Perhaps there’s a sense the country has implemented deeper cuts than many expected after it walked away from the previous OPEC+ deal. Or perhaps the Saudis feel it’s unwise to antagonize such an important partner, especially one that’s historically been treated with suspicion by OPEC.

The next problem to pop up may be even more embarrassing for Saudi Arabia: compliance questions concerning the United Arab Emirates, the kingdom’s long-time ally. By its own admission, the UAE has pumped about 100,000 barrels a day more than it should have in August due to peak summer electricity demand, putting its compliance at 82%. But that may be an understatement, according to the so-called secondary sources OPEC relies on to monitor its deal.

This spells the potential for more unwanted friction when the JMMC meets later this week. It’s a really bad sign that one of the more disciplined members is now changing its tune. It will make it more difficult to convince other producers to continue to toe the line. It’s a real shame, coming just as the group would prefer to celebrate its successes rather than dwell on its challenges.

And there have been successes, a major one being the record 9.7 million barrels a day cut from global supply thanks to the current OPEC+ arrangement with 10 non-OPEC allies that Saudi Arabia is trying to hold together.

I remain convinced that, despite the group’s very obvious shortcomings, oil markets have been a lot less volatile because of its existence over the past 60 years. A world without OPEC, or some similar group, would be far from paradise.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

To contact the author of this story:

Julian Lee at jlee1627@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story:

Melissa Pozsgay at mpozsgay@bloomberg.net