Lie detectors are creeping into UK policing and they still don’t work

Data obtained using the Freedom of Information Act reveals the opaque and inconsistent use of the polygraph machine by police forces across England and Wales. However, their use is expanding

by Amit Katwala

Until recently, the most famous application of the polygraph machine in the United Kingdom was probably the Jeremy Kyle Show. Unlike in the United States, where there are an estimated three million tests a year, the so-called ‘lie detector’ has never really caught on in Britain. But that’s starting to change.

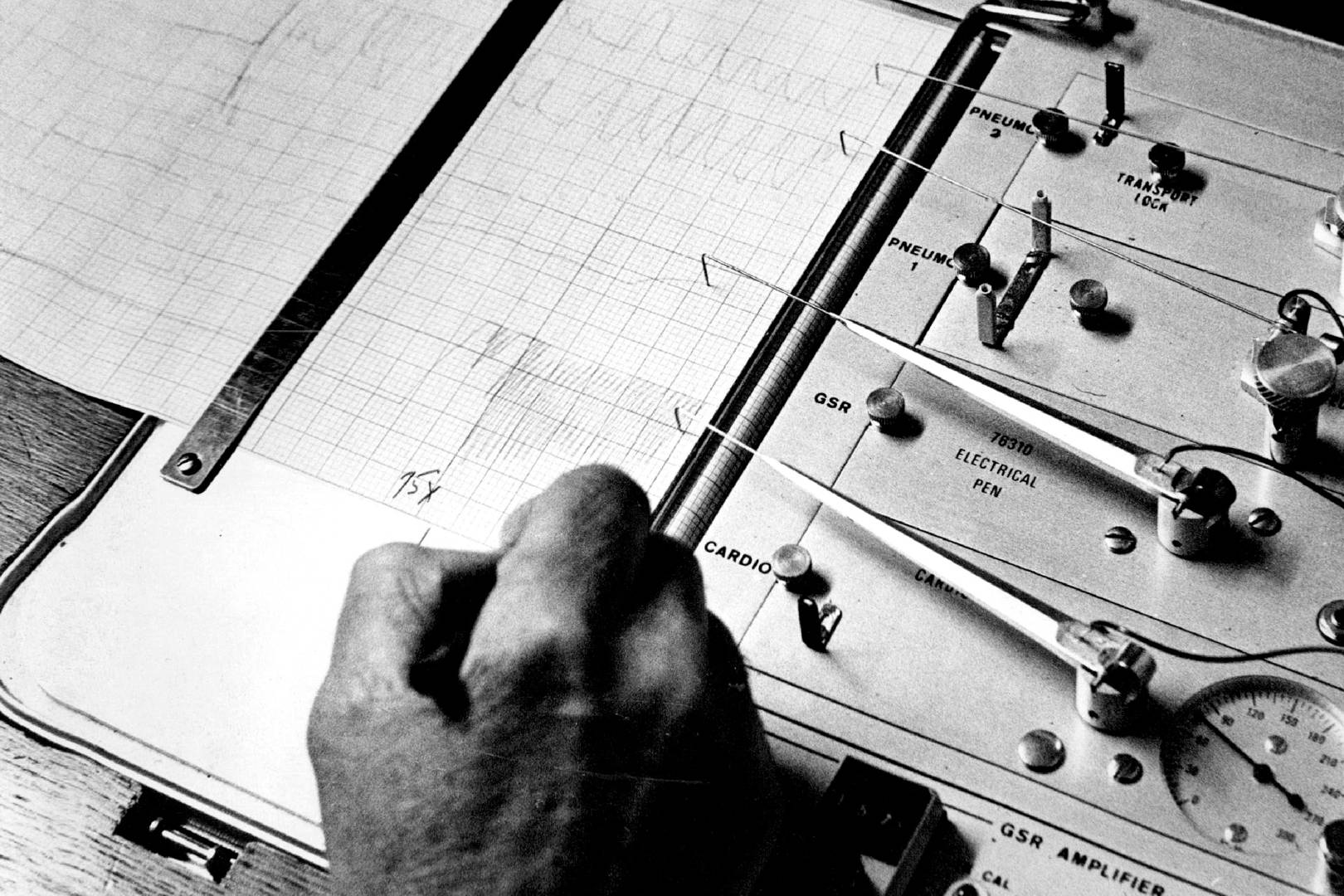

The machine – which measures breathing, heart rate, blood pressure and sweat in an attempt to detect deception – is slowly creeping into British policing. Since 2007, it’s been used with sex offenders to assess whether they are likely to reoffend if released. Now, two bills working their way through Parliament are set to expand the use of the polygraph further.

The first targets domestic abusers deemed at high-risk of causing serious harm. The Domestic Abuse Bill makes provisions for a three-year pilot study during which 300 offenders will take a lie detector test three months after release, and then every six months after that. They won’t be jailed for failing the test – but could be if they refuse to take it, or if they try to trick it, according to the Home Office, or if the test shows their risk has escalated.

The second is the Counter Terrorism Bill, which will impose mandatory polygraph examinations on high risk offenders who have previously been convicted of terror-related offences. Introducing polygraph tests in these situations is one of 50 recommendations made in response to the 2019 London Bridge attack perpetrated by Usman Khan, who was out on licence when he killed two people and injured three others.

But there’s a big lack of transparency around the extent to which the polygraph is already being used by police forces and probation services in this country, according to the authors of a new piece of research.

Marion Oswald and Kyriakos Kotsoglou of Northumbria Law School sent Freedom of Information Act requests to all UK police forces asking if and how they were using the polygraph. They were largely reluctant to provide details. Of the 46 replies, 37 issued a ‘neither confirm not deny’ response – an option open to public bodies if they believe that releasing the information would be exempt under the transparency law. Exemptions can be used if releasing information could pose a potential operation or security risk.

After requests for the initial decisions to be reviewed, some forces stated that they do not use the polygraph in an ‘overt’ capacity, although they did not explain what they meant by that term. The researchers say this means police forces could be using polygraphs in “investigatory work or in some covert context”.

Only five forces – Gwent Police, Merseyside Police, Police Scotland, Wiltshire Police and The Port of Dover Police – denied the use of polygraphs entirely. “I don’t think we can tell exactly how police forces are using the polygraph, and that’s a concern,” says Oswald.

The direction of travel is clear, however. Although a 2014 statement from the Association of Chief Police Officers (now the National Police Chief’s Council) strongly discourages its use, and the polygraph is not admissible as evidence in court, there is no legal framework to stop police forces attempting to use it during interrogations or as part of an evidence gathering process in the UK. It has, for example, been trialled with individuals suspected (but not convicted) of committing an online sexual offence.

During their research, Oswald and Kotsoglou also discovered that Hertfordshire Police was using a polygraph as a bail condition in association with a non-custodial sentence as part of its C2 rehabilitation programme. “There is no legislation that covers the use of the polygraph in that way,” says Oswald. At the time of writing Hertfordshire Police had not responded to a request for comment on their use of the system.

The reason Oswald, Kotsoglou and others are so concerned about the proliferation of the polygraph is that the research shows that it doesn’t work, and that the justifications for the use of the test are undermined by how it’s actually been used in practice.

Polygraph tests have been repeatedly debunked in independent studies dating back decades. “We cannot stress enough that ever since the first deployment of the polygraph, appellate courts, scientific organisations, and last but not least academic discourse have continuously and nearly unanimously criticised, and rejected this method as unscientific,” write Oswald and Kotsoglou.

Although they can help coerce suspected criminals into making confessions – and indeed the use of the polygraph with sex offenders has led to an increase in information disclosed during interviews – there’s often no way of testing whether those confessions are actually accurate. It has been criticised as a tool of psychological torture. “If you put pressure on people, they will tell you whatever they think you want them to tell you,” says Kotsoglou. “This destroys the evidential value of the statement.”

The machine is also relatively easy to beat with a little training and organisation, which raises questions over its efficacy with suspected terrorists in particular. “Deciding whether to release an offender into the community is difficult, and this looks like a solution which gives you some certainty,” says Kotsoglou. “But it’s based completely on a false premise.”

There appears to be little consistency in how the tests are applied and conducted in different areas, according to the researchers. Some forces are using their own officers, while others are outsourcing the tests to external examiners. The Home Office claims its examiners are highly trained and carefully scrutinised – but in truth, most police forces are using the guidelines and training set down by the American Polygraph Association. “There is no independent objective measure,” says Oswald. It is, she argues, the equivalent of the polygraph industry marking its own homework.

Other concerns include the danger that polygraph tests could shift from being used to corroborate other forms of evidence into a way to pressure the defendant into giving up information, which could be used to obtain a search warrant and secure evidence in a non-objective manner already influenced by a flawed test result, says Kotsoglou.

The government knows all this. The drawbacks of polygraphs have been debated in parliament as far back as the 1980s. But the lie detector is a convenient measure for governments to turn to when they need to look tough on crime and want easy PR wins – it’s no coincidence that sex offenders, domestic abusers and terrorists are the three groups at the forefront of polygraph use in this country. The SNP sparked tabloid fury recently for daring to raise concerns.

There are some cases where the polygraph may be useful – in determining whether a rehabilitation programme is working, for example. “The challenges posed in monitoring terrorist offenders are such that polygraph testing is a sensible additional tool,” the UK’s Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation recently said in response to the government’s planned changes. But its slow creep into policing is alarming, and using it as a means to detect whether a terror suspect is telling the truth is deeply problematic.

In their paper, Oswald and Kotsoglou argue for an urgent halt on any further use of the polygraph, along with an independent, public investigation into its current use – with regulation, independent oversight and scrutiny.

“We are already on the slippery slope with regards to the polygraph,” says Kotsoglou. He calls it zombie forensics, and agues that the polygraph will give society a false sense of security based on an unscientific method. “This becomes a threat in terrorism,” he says. “A false sense of security could have literally fatal consequences.”

Amit Katwala is WIRED's culture editor. He tweets from @amitkatwala

More great stories from WIRED

🐾 A liver disease is putting the Skye Terrier’s existence at risk. Doggy DNA banks could help save it

🔞 As AI technology gets cheaper and easier to use, deepfake porn is going mainstream

🏡 Back at work? So are burglars. Here’s the tech you need to keep your home safe

🔊 Listen to The WIRED Podcast, the week in science, technology and culture, delivered every Friday