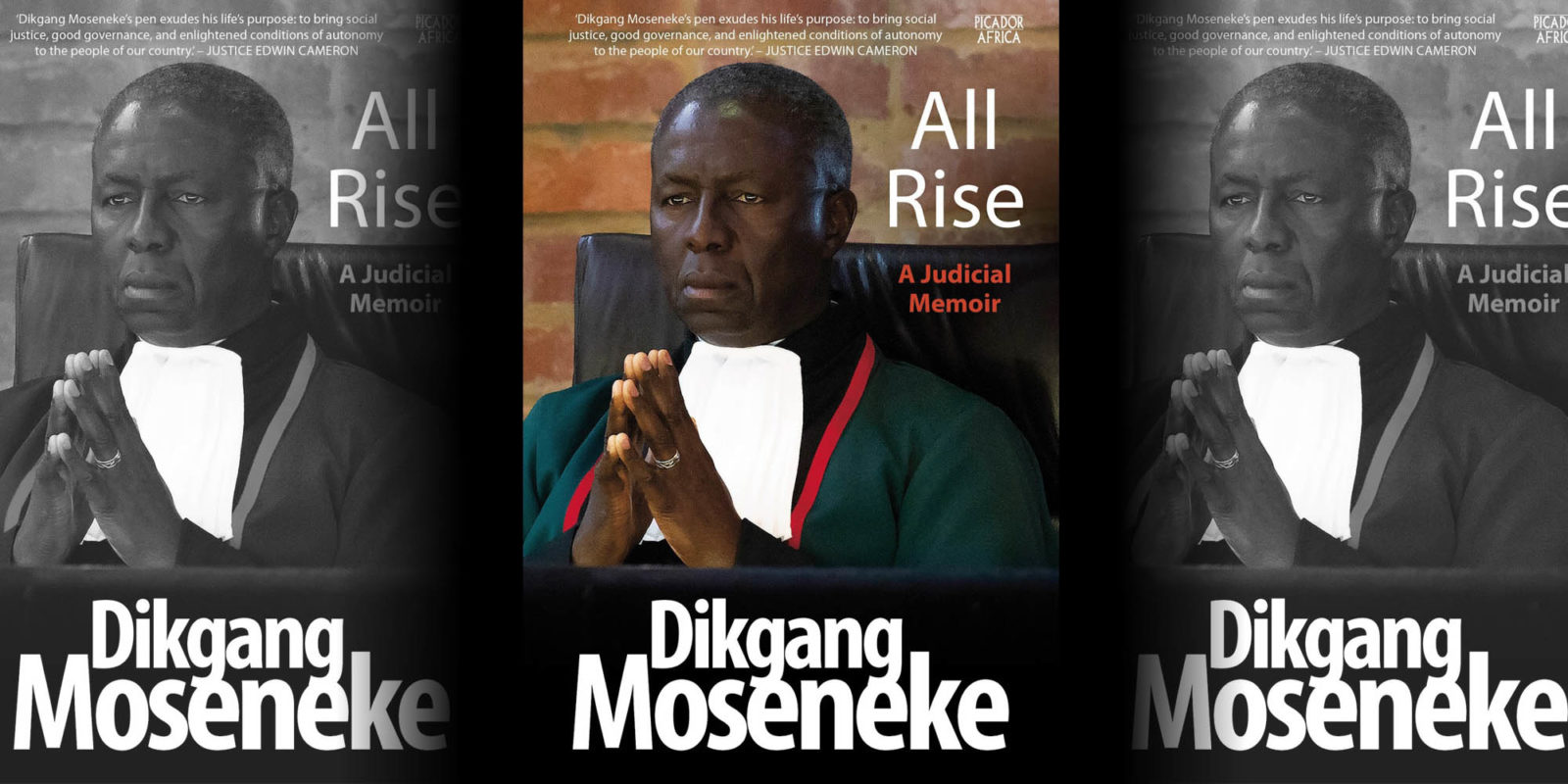

All Rise: Dikgang Moseneke gives a bird’s-eye view of constitutional issues in South Africa

by Anton KatzIn his latest book, All Rise, Dikgang Moseneke – who has a rich eye for what makes a better society for all – reveals how the Constitutional Court often sailed through stormy seas. The book gives a bird’s-eye view of the constitutional issues of the time.

On 13 November 2016 I gave Justice Dikgang Moseneke’s personal memoir, My Own Liberator five out five stars on the amazon.com website. I wrote “his memoir was not only an important contribution to the library of books dealing with the harshness, stupidity (silliness) and sheer criminality of apartheid race discrimination, but also a delightful description of the courageous journey of a 15-year-old boy jailed for 10 years solely for standing up to that criminality. Moseneke demonstrates that hard work and education are important tools for a successful and rewarding life. Diligence and industry are necessary to pursue social justice on every level. What a special book.”

Moseneke’s second book, his judicial memoir, is also special. But in distinctive ways. The Justice reminds us that judicial memoirs are popular in the United States, and that he had to summon much energy to produce his. But for all South African lawyers, and indeed anyone with a passing interest in the first two decades of post-apartheid South African politics, All Rise is fascinating on many levels. Moseneke’s industry and energy in producing it are welcome.

The book makes a serious and positive contribution to South Africans’ knowledge and insight into many interesting issues. All Rise shines an important light on key aspects of governance in South Africa in the first decades of the existence of the Constitutional Court. And the shining of that light is a marker, as Justice Moseneke would have it, of the hygiene of South Africa’s democratic project.

Unlike many of the US judicial memoirs Moseneke referred to in his book, he does not spill the beans on how some of the more difficult Constitutional Court cases were decided. In many multiple-judge panels, horse trading over particular aspects of the result and the reasoning in the case is common. So, one judge might give his concurrence and create a majority in an unfair dismissal matter if that judge is promised help in obtaining a majority in a difficult case about mining rights.

In the US Supreme Court, the fractious debates over abortion rights and the death penalty often created alliances and the swapping of voting favours. Moseneke, true to his reputation for absolute integrity, does not tell us about any of those internal judicial debates. But what he does do is convey a high-level picture of how the Constitutional Court often had to, and did, sail through stormy (political) seas. The book gives a bird’s-eye view of the constitutional issues of the time.

…despite its serious tone, All Rise has occasional humour and cheer. A story involving the author of this review demonstrates Moseneke’s ability, even in a limited way, to laugh at himself.

There is a special emphasis on the Court’s relationship with some of Moseneke’s colleagues in the anti-apartheid struggle who had sought and obtained political power. Aside from the broad insights into the role of the Constitutional Court under the leadership of Arthur Chaskalson, Pius Langa, Sandile Ngcobo and Mogoeng Mogoeng – and his relationship with each of the four Chief Justices – he tells some great stories. For example, the disbanding of the Scorpions, Justice Khampepe and his report on the illegality of Robert Mugabe’s success in the 2002 Zimbabwe election sent to President Mbeki, the Hlophe affair, the unlawful attempt by President Zuma to extend the term of office of Chief Justice Ngcobo and Moseneke’s chairing of the Judicial Services Commission’s interview of Mogoeng for the position of Chief Justice are all featured.

Two spoilers suffice for purposes of this review. First was an interaction with then president Jacob Zuma. Many judicial battles had ended up or were destined to end in the Constitutional Court after Schabir Shaik and Zuma had been charged with crimes arising from the so-called Arms Deal.

During this time, one of Chief Justice Langa’s last important tasks was to arrange a national judge’s conference in June 2009. President Zuma, in his second month as president, was invited to deliver the opening address. After the president’s blue light brigade arrived, Moseneke, who was the Deputy Chief Justice, was assigned to keep the president company in a holding room while Langa attended to the opening of the plenary. Moseneke and Zuma had been young men and had come to know each other “very, very well and were close comrades” when they served their 10-year sentences of imprisonment on Robben Island.

That closeness was reflected in that after Moseneke married, he and his bride went on honeymoon to Durban. It was Jacob Zuma who met the newly-weds at the Durban airport and showed them around. Now, so many years later in the holding room, they affectionately embraced. Zuma’s court battles were well on their way. One of the liberation fighters had risen to the pinnacle of political power and become the President of South Africa. The other liberator was the Deputy Chief Justice. Moseneke assured Zuma that he recognised and respected his rise to the presidency. An “eerie silence crept in” until the president commented: “… the job of a judge is difficult.” Jacob Zuma added, “I understand your predicament.”

Zuma then told the story about Gaddafi and judges. Gaddafi had told Zuma, on the sidelines of an African Union summit, that he thought Libya and South Africa together could rule the entire African continent. Zuma giggled and asked about the judges in Libya. Gaddafi responded: “What judges?” Zuma then told Moseneke that he told Gaddafi: “in my country the judges will never allow me, the president, to do what you say we do if it is not in the Constitution. Wherever you turn to, the judges are all over you,” and Zuma chortled at some length.

Second, despite its serious tone, All Rise has occasional humour and cheer. A story involving the author of this review demonstrates Moseneke’s ability, even in a limited way, to laugh at himself.

In his 14 years as a Constitutional Court Justice, Moseneke was part of the decision-making in 411 written judgments, of which 273 were unanimous judgments. He wrote more than 50 substantive judgments, 15 of which were dissenting judgments, and participated and co-decided many thousands of applications.

A case involving a Russian dancer, Ms Tatiana Malachi, who had been unlawfully arrested and detained, came before the Constitutional Court. Justice Moseneke recalls she had “considerable dancing skills and a body and face to match the part.” During my argument on behalf of Ms Malachi, Moseneke probed me on some difficult legal aspects of the case. He then out of the blue asked me: ” Mr Katz, is the applicant, Ms Tatiana, in court?”

After the hearing, his female colleagues on the bench were not amused. Why should she be here, they queried? Moseneke explains that he had no valid defence, except that he must have been overcome by a “boyish instinct to set [his] eyes on the fairytale Russian dancer who was at the centre of the controversy.” Now that the Constitutional Court hearings are featured on YouTube and Zoom, Moseneke’s “Tatiana misstep” couldn’t occur.

May I end by offering some advice. In giving it, I can do a bit of silly bragging. Most, but not all my clients follow my counsel. When they follow my advice, they often, but not always, succeed in their case. If they reject my advice and take an opposite path, they more often than not lose their case. So, my advice and counsel is: buy and read Justice Moseneke’s judicial memoir, All Rise. It will definitely be well worth the money and time spent. Although it deals with some daunting features of South African life, it is an easy read. Reading All Rise will enrich your insights into many aspects of personal and power relations of the public faces of the South African judiciary over the past 20 years.

In his 14 years as a Constitutional Court Justice, Moseneke was part of the decision-making in 411 written judgments, of which 273 were unanimous judgments. He wrote more than 50 substantive judgments, 15 of which were dissenting judgments, and participated and co-decided many thousands of applications.

Interestingly, in his description of the many cases he was a part of, there is one on which he acknowledges he might have “voted differently” if he’d had another opportunity.

That case was Volks v Robinson. The majority of the Constitutional Court, of which Moseneke was a part, effectively held that the Constitution permitted laws that differentiated between married different-sex partners and those different-sex couples who enjoyed a stable permanent relationship akin to a marriage relationship.

The majority of the Constitutional Court rejected the notion of a “common law marriage” giving rise to rights and obligations. Justice Moseneke is probably correct to reflect that he might have been on the wrong side in Volks.

I trust Justice Moseneke will not mind if I capture the commencement of the last case he sat on in the Constitutional Court on 12 May 2016. I represented Ms Kunjana, whose house had been unlawfully raided in a police search for illegal narcotics. Advocate Andrew Breitenbach SC appeared for the police. Justice Moseneke was presiding as Deputy Chief Justice.

The case was called by the chief clerk. Breitenbach stood up and chimed: “I appear for the applicant, the Minister of Police.” Moseneke DCJ said: “Thank you, Mr Bredenkamp.” I caught Deputy Chief Justice Moseneke’s eye and mouthed to him “Breitenbach!!!” Moseneke DCJ took a couple of seconds, then said: “Oops, I’m sorry Mr Breitenbach. Thank you.” I then stood up and said: “I appear for the respondent, Ms Kunjana.” Quick as a flash, Deputy Chief Justice Moseneke responded: “Thank you Mr Levy. Oops, I’m sorry! Thank you, Mr Katz.”

Justice Dikgang Moseneke was and is a brilliant jurist and human being. He has a rich eye for what makes a better society for all. And he has a great sense of occasion, as his judicial memoir so keenly demonstrates. The conclusion of Justice Edwin Cameron’s foreword to All Rise is apt. He says the book is important and memorable. It soberly gives readers the incontestable facts and invites them to make their own assessments. DM

Advocate Anton Katz SC has appeared on multiple occasions before Justice Moseneke in the Constitutional Court.

- Constitutional Court

- Edwin Cameron

- Jacob Zuma

- Pius Langa

- Schabir Shaik

- TAGS Dikgang Moseneke

- Volks v Robinson

Anton Katz

Comments - share your knowledge and experience

Please note you must be a Maverick Insider to comment. Sign up here or sign in if you are already an Insider.

Everybody has an opinion but not everyone has the knowledge and the experience to contribute meaningfully to a discussion. That’s what we want from our members. Help us learn with your expertise and insights on articles that we publish. We encourage different, respectful viewpoints to further our understanding of the world. View our comments policy here.

MAVERICK INSIDERS CAN COMMENT. BECOME AN INSIDER

No Comments, yet