Flaws in Georgia’s Election System Let 1,000 People Vote Twice

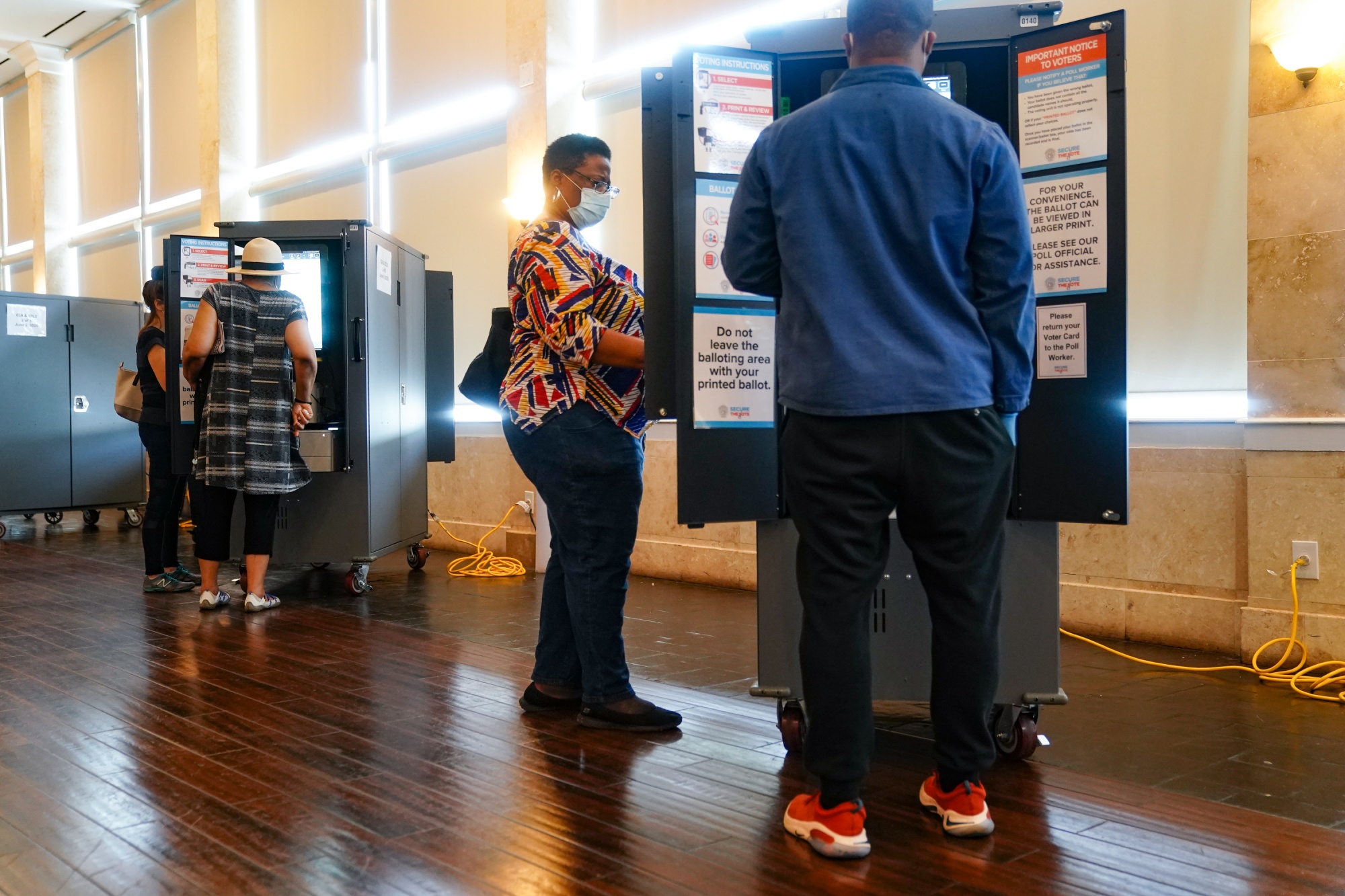

A double-voting fiasco—a combination of glitchy technology and human error—doesn’t bode well for November.

by Kartikay MehrotraLynn Elander, a semi-retired marketing executive in Atlanta, voted twice in Georgia’s presidential and U.S. Senate primary races this year. She didn’t mean to, she says. But Georgia’s election system let her do it.

Elander voted first in March, in advance of the state’s March 24 presidential primary, and then again in late May, after coronavirus fears delayed the original primary twice. She went to the polls the second time to vote on down-ballot races that hadn’t appeared on the March ballot. But when she inserted her ballot card into the machine, it pulled up all the races, including those she had already voted on. She assumed her earlier ballot had been discarded and cast her vote again.

Elander is now part of a double-voting scandal in Georgia that flared up less than a week after President Donald Trump advised Americans to try to vote twice, which is illegal. Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger announced on Sept. 8 that 1,000 Georgians cast double ballots in the primary. Sixty percent of them were Democrats, he said. These facts quickly—and erroneously—gave oxygen to claims that mail-in voting invites Democratic election fraud, including from Fox News’s Sean Hannity. On Sept. 12, Twitter put a warning label on a Trump tweet that encouraged North Carolina voters to vote by mail but then to go to the polls and vote again if they thought their first ballot hadn’t been counted.

But mail-in voting isn’t the culprit in Georgia’s double-voting fiasco (which did not change the outcome of any race, Raffensperger said). To blame were an overwhelmed, understaffed state election system and sign-in voting computers that failed to detect who had already voted. Although only a tiny fraction of Georgia’s electorate is implicated, the problems could preview similar election woes this fall in Georgia and other battleground states, where the presidential race could come down to a small number of contested votes.

Raffensperger has threatened to prosecute alleged offenders, and the names of two have been made public. The first is Elander; the second is Hamilton Evans, a 73-year-old from Long County, who brought his wife to the polls on June 9 after voting early himself. A poll worker asked for his ID while he was waiting, and he says he handed it over to see what would happen. She gave him a ballot card. He used it—again, to see what would happen, he says—and then immediately headed to the local sheriff’s office.

“I went to report it,” Evans says. “I thought, ‘This isn’t right. There’s something wrong with the system. It needs to be fixed.’” It was Evans' double vote that indirectly kicked off Raffensperger's investigation statewide. “Don't know yet,” Evan says when asked if he’s in criminal trouble.

Election controversies are nothing new in Georgia. The state has aggressively culled voter rolls and, until this year, it used what critics called the most insecure voting machinery in the U.S. Last year, it replaced its voting technology. The June 9 primary was the statewide debut of new, computerized ballot-marker voting machines supplied by Dominion Voting Systems. On primary day, however, in-person voters had to wait hours in line after delays involving some of these machines, which are now the subject of a lawsuit.

Georgia utilizes electronic poll books for voter check-in—supplied by St. Louis-based KnowInk—and scanners to count provisional ballots. Like many states, it uses iPads with proprietary software to verify that voters are eligible to receive a ballot. But dangling from those iPads are readers to scan voter barcodes from paper and program them onto ATM-like ballot cards, which voters then feed into touchscreen machines. For voters who have received an absentee ballot but want to vote on Election Day, poll workers must manually punch the voter’s details into the iPad to program the ATM card.

In June, some of the poll pads failed to start up or to connect to Georgia’s central elections database. A preset login password—the same across all devices in the state—sometimes didn’t work, according to court filings in longstanding litigation over the state’s voting practices, led by a group called the Coalition for Good Governance. Crucially, as the public learned last week, the pads were unable in many cases to distinguish between someone who’d already cast a ballot and someone who had not. According to the state, the data that would have allowed that hadn’t reliably been keyed in.

Malfunctions spanned the new voting system, according to the Coalition for Good Governance’s lawsuit. Cybersecurity experts argue that any election under this system is flawed, and the system lacks the transparency needed to verify outcomes. It should be gutted before November, say the plaintiffs in the litigation. Georgia’s state election officials contend that the June debacle had more to do with conducting an election in the Covid-19 pandemic era than any systemwide gaps in its voting technology.

Although the state has yet to offer a breakdown of how its 1,000 double voters cast their ballots, most are likely to have voted absentee first—either by mail or via early, in-person voting—and on Election Day second, according to Gabriel Sterling, Georgia’s voting system implementation manager. Sterling says the state’s voting technology works fine, and “Covid was the biggest driver” behind the double voting.

A state investigation is ongoing, but Sterling says he suspects that untrained, stressed-out poll workers who failed to follow proper procedures were a chief reason for the double votes. The primary was short on experienced poll workers and polling places, due to fears over Covid-19. In the state’s biggest county, Fulton, local election officials had to hire more than 200 poll workers the weekend before the June 9 primary.

According to Sterling, the main problem with early, in-person voting was that poll workers failed to manually input data in real time on who was voting, so a backlog built up. This meant that electronic poll books on Election Day wouldn’t show that a person had already voted. Likewise, voters who requested a mail-in ballot but didn’t use it are supposed to bring it to the polls to have it canceled before voting in person. If they didn’t bring it, poll workers could determine electronically only that they had requested a ballot—not whether they had cast it. And poll workers had to cancel the early ballot over the phone with an election official, a time-consuming step that Sterling says may have been skipped by poll workers facing long lines.

When voters decided to ditch their absentee ballots for in-person voting, the check-in machines provided some resistance. But it was easily circumvented by poll workers with the press of a single button. Less than two months away from election day, the state is still mulling the addition of a passcode, which may prompt volunteers to double-check the voter's status.

In an Aug. 19 declaration to the court, a local election official in Cherokee County confirmed that the pads “can issue an unlimited number of voter access cards to same voter, with no override pass-code or anything required from the election office.” To critics of Georgia elections, including the plaintiffs in the lawsuit—which has been meandering through state courts since 2017—the failure of poll books to prevent double voting is evidence that Georgia’s new voting system should be ditched for hand-marked paper ballots scanned and tabulated by industrial scanners.

“If Georgia’s poll-pad system has been set to permit unlimited issuance of voter access cards for a single voter, this would constitute a high risk and non-standard election process,” Hari Hursti, a cybersecurity and election security expert, said in a legal declaration supporting plaintiffs' argument.

The dearth of trained poll workers and polling places was aggravated, Sterling says, by third-party groups—including advocacy groups and both major political parties—texting and emailing warnings that early or absentee votes might not have counted and urging people to go to the polls. “And now, in this case, we have the president of the United States doing it,” he says of Trump’s recent calls to vote twice.

Lynn Elander is waiting to see what happens next. When she arrived to vote early a second time in late May, Elander recalls, the poll books wouldn’t spit out her voting card. A poll worker intervened and produced one manually, which didn’t appear to be a big deal. “No one articulated this, but it seemed like this was a usual occurrence,” she says. “The poll workers treated it as though this was a problem they’d already had many times before.” Now, she’s worried about felony charges.

(Updated in the 7th paragraph with litigation involving the June 9th Georgia primary)