Alien life

Scientists find gas linked to life in atmosphere of Venus

Phosphine, released by microbes in oxygen-starved environments, was present in quantities larger than expected

by Ian SampleTraces of a pungent gas that waft through the clouds of Venus may be emanations from aerial organisms – microbial life, but not as we know it.

Astronomers detected phosphine 30 miles up in the planet’s atmosphere and have failed to identify a process other than life that could account for its presence.

The discovery raises the possibility that life gained a foothold on Earth’s inner neighbour and remnants clung on – or floated on, at least – as Venus suffered runaway global warming that made the planet hellish.

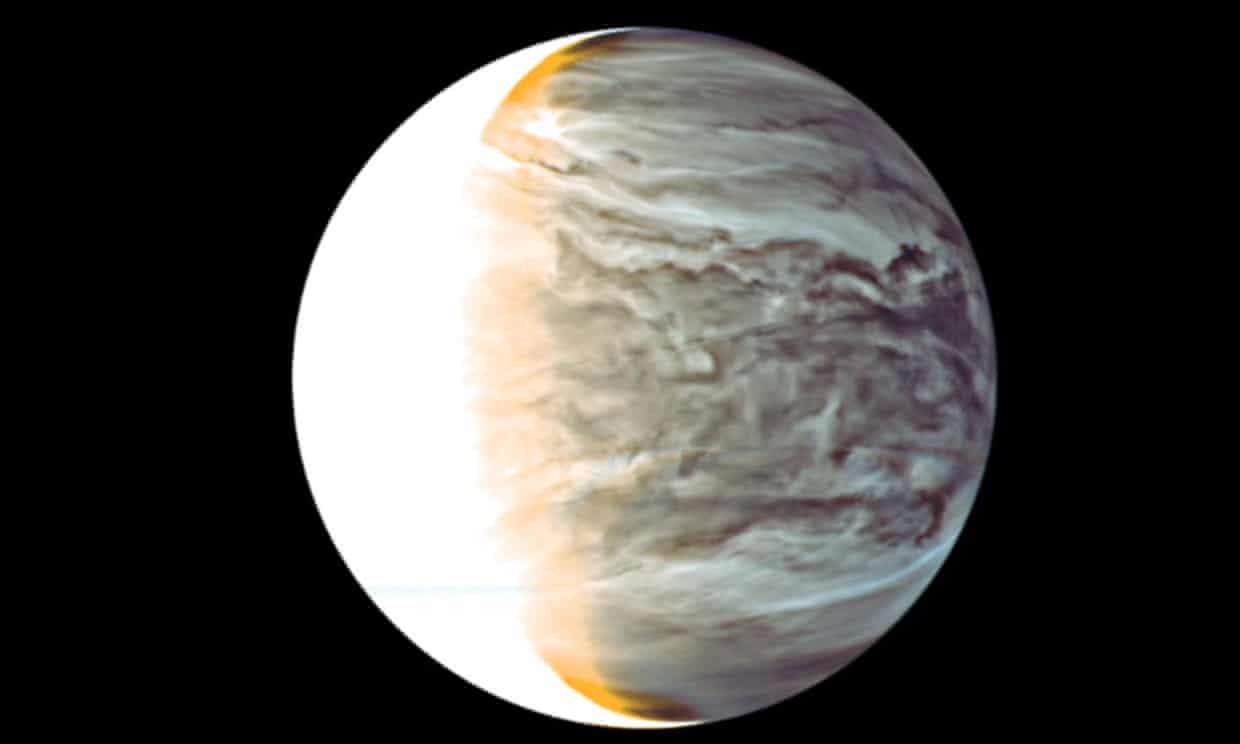

For 2bn years, Venus was temperate and harboured an ocean. But today, a dense carbon dioxide atmosphere blankets a near-waterless surface where temperatures top 450C. The clouds in the sky are hardly inviting, containing droplets of 90% sulphuric acid.

The conditions on Venus are so deeply unpleasant that many scientists believe the planet is dead. Rather than coming from floating Venusians, they suspect phosphine arises from more mundane processes.

“It’s completely startling to say life could survive surrounded by so much sulphuric acid,” said Prof Jane Greaves, an astronomer at Cardiff University, leader of the team who made the discovery. “But all the geological and photochemical routes we can think of are far too underproductive to make the phosphine we see.”

On Earth, phosphine gas is released by microbes in oxygen-starved environments, such as lake sediments and animals’ innards. Other production routes are so extreme – the bellies of Jupiter and Saturn – that on rocky planets, phosphine is considered a marker for life.

As a test-run for searching for life beyond Earth, Greaves observed Venus in 2017 with the James Clerk Maxwell telescope in Hawaii, and in 2019 with the Alma telescope in Chile. Both revealed the signature of phosphine in the upper cloud deck of Venus.

Greaves first spotted the phosphine signal late one day in December 2018 as she was about to leave work. “There wasn’t anyone to talk to and I remember thinking the best way to celebrate was to make a curry, so I drove off to Sainsbury’s,” she said.

The observations point to trace levels of phosphine, about 20 molecules per billion, at least 30 miles high in the Venusian sky. Most appears at the mid-latitudes with none detected at the poles, the scientists report in Nature Astronomy.

While the phosphine may come from a mysterious new source, the researchers’ calculations rule out known chemistry and show that volcanoes, lightning and micrometeorites would all create too little. “The rates of production are so small, and the rates of destruction great enough, that you’d have 1,000 times too little,” said Paul Rimmer, an astrochemist on the team at the University of Cambridge.

To generate the amount of phosphine observed, Earth microbes would need to work at only 10% of their maximum productivity, the scientists say.

Sara Seager, a planetary scientist on the study at MIT in the US, called the finding “mind-boggling”. She hypothesises a lifecycle for Venusian microbes that rain down, dry out and are swept back up to more temperate altitudes by currents in the atmosphere.

Charles Cockell, an astrobiologist at the University of Edinburgh, said that, rather than hinting at life on Venus, the work raises questions about phosphine as a “biomarker”.

“A biological explanation should always be the explanation of last resort and there are good reasons to think the Venusian clouds are dead. The concentrations of sulphuric acid in those clouds are more extreme than any known habitat on Earth,” he said.

Lewis Dartnell, an astrobiologist at the University of Westminster, said the findings would spur more work. “This is a huge opportunity for follow-on observations from Earth-based telescopes, and ideally to scrutinise these droplets in the Venusian atmosphere with a balloon probe drifting through the acidic clouds.”