Disinformation in a time of Covid-19: Weekly Trends in South Africa

by Thandi Smith and William BirdWeek14: Complaints at Crossroads – the complications and challenges of combined digital offences.

A crisis such as the Covid-19 pandemic creates a perfect opportunity for those who wish to cause confusion, chaos and public harm, and mis- and disinformation enable them to do just that. This week we look at how complaints can often blur lines between disinformation and incitement and or hateful speech.

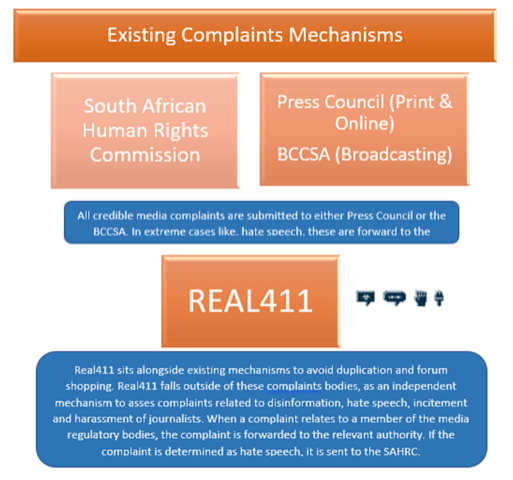

Through the Real411 platform, Media Monitoring Africa has been tracking disinformation trends on digital platforms since the end of March 2020. Using the Real411 platform we have analysed disinformation trends which have largely focused on Covid-19. To date, the platform has received 681 complaints, of which 657 have been assessed and action taken. As outlined in the graphic below, only 36% of the complaints have been assessed as disinformation, with many other complaints containing other digital offences.

Before the launch of the new and improved Real411 platform, and after extensive consultation with a wide variety of stakeholders, we knew that we needed to create a platform that would cater to multiple digital offences. As a result, the digital offence categories on Real411 include Disinformation, Hate Speech, Incitement to Violence, and Harassment of Journalists Online. What we did not anticipate, was how often these categories would cross over – in other words, how the content submitted would have elements of multiple categories.

An example of this is when disinformation has connotations of incitement to violence, or when disinformation has elements of hate speech.

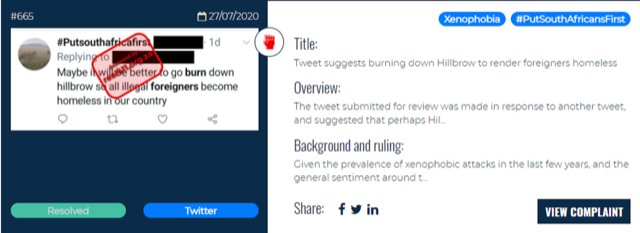

Complaint 665 (detailed below) for example, deals with elements of hate speech (which does not fulfil the legal definition of hate speech) as well as incitement, and xenophobia. Content such as this creates a challenge because it does not meet the test for hate speech, yet it is still incredibly problematic, offensive, and harmful.

Running real411 has been useful in testing not just the systems but the criteria used. While the criteria are all rooted in our existing laws and Constitution, the system is showing how challenging it is to travail the balancing of freedom of expression against the digital evils. While there are some examples of content that is clearly disinformation, the lines are often blurred. When it comes to hate speech and incitement, for example, the challenge is even greater.

In the case of hate speech, we are hoping for some clarity, after the Jon Qwelane matter has been heard, as to not only the status of sections of our existing law, but also on the criteria as to what actually constitutes hate speech. In South Africa, we have multiple relevant authoritative bodies that deal with hate speech, racist speech, and criminal offences. But what happens when it’s not as clear and defined as it needs to be in order to refer a valid complaint to say, the South African Human Rights Commission, or the Equality Court? The graphic below explains how the Real411 platform complements the existing regulatory environment within which we currently operate.

Racism was in the spotlight in early September, largely as a result of a racist advert by Clicks. Given the hurt, anger and pain caused by racism, it’s hardly surprising that together with the racism and responses to it, we also saw content that mixed racism and incitement.

This complaint 735 was about content that was released on the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) Facebook page, about a call that was made to Marshall Dlamini, Secretary-General of the EFF. The purpose of the call seems to have been to threaten Dlamini’s life. The caller, in making the threats, also frequently uses the “K” word and refers to all black people as baboons. It is an absolutely revolting tirade, sickening, demeaning and grotesque. Mr Dlamini deserves huge credit for his largely dignified response to the caller.

We thought it would be useful to look at the elements that constitute incitement. Three separate criteria need to be met for content to be considered incitement to violence. In order to move to the next criteria, each must be met. In broad terms the criteria are:

- There has been conduct, speech or publication of words.

- It might reasonably be expected that the natural and probable consequences of this act, conduct, speech or publication would, under the circumstances, be the commission of public violence.

- The public violence would be committed by members of the public generally or by persons in whose presence the act or conduct took place or to whom the speech or publication was addressed.

On the first test, we know from the call that there has indeed been conduct, speech and words with overt threats to kill. On the second test, two possible elements arise. It could be argued that any black person who hears the call might be so angered that they themselves become violent. The problem with this is that while it is a possibility, it is not a natural or probable consequence that on hearing the speech people would commit public violence.

Certainly, there is no suggestion in the response from Mr Dlamini that that should be the response to the threat. Alternatively, it can be argued that the threat itself might lead to the commission of public violence. This is unlikely, given that the call was made not on a platform but in the form of a one-on-one phone call – and only became public when posted to Facebook by the EFF on its official page – and the person making the threats was the one threatening to carry them out. While also likely illegal, the caller is not calling on other people to assault all black people.

The third test will therefore fall away because the second test’s criteria haven’t been met. But even if it’s assumed the second test had been met, it hardly seems reasonable that another person who heard the words would be incited to commit public violence. Indeed, in listening to the call there is nothing that would have incited a rational, reasonable person to commit violence or follow through on the threats made.

While the call is therefore deeply offensive and riddled with the crassest racism, and despite the threats to Mr Dlamini, it doesn’t in our view constitute incitement to violence. This is not to suggest that Mr Dlamini may not have legal avenues of recourse available to him.

If we return to 665, it is clear how in that case, in context, the public tweet was part of the xenophobic #putsouthafricafirst and can be seen as incitement. While it doesn’t clearly ask people to burn things down, it does suggest that maybe if people do so, then foreigners would be homeless. Grossly irresponsible to make that assertion, as if arson in a highly built-up area would not be extremely dangerous.

We hope this week we have offered some insight, not just into the Real411 workings but also into how often elements of digital evils, like disinformation, hate speech and incitement go hand in hand. Previously we have covered how disinformation tends to work on our fears and anxieties. What seems to be emerging is that where there are elements of hate speech, of incitement to violence, or disinformation, they should be seen as flags warning to be deeply sceptical of any similar content. Again, the easiest way of helping prevent the spread of these digital evils is not to share them and to share kindness and compassion instead. DM

William Bird is director of Media Monitoring Africa. Thandi Smith is head of programmes at Media Monitoring Africa.

Thandi Smith and William Bird

Comments - share your knowledge and experience

Please note you must be a Maverick Insider to comment. Sign up here or sign in if you are already an Insider.

Everybody has an opinion but not everyone has the knowledge and the experience to contribute meaningfully to a discussion. That’s what we want from our members. Help us learn with your expertise and insights on articles that we publish. We encourage different, respectful viewpoints to further our understanding of the world. View our comments policy here.

MAVERICK INSIDERS CAN COMMENT. BECOME AN INSIDER

No Comments, yet