The Observer

‘Why I’m putting the faces of black British heroes on grocery shelves’

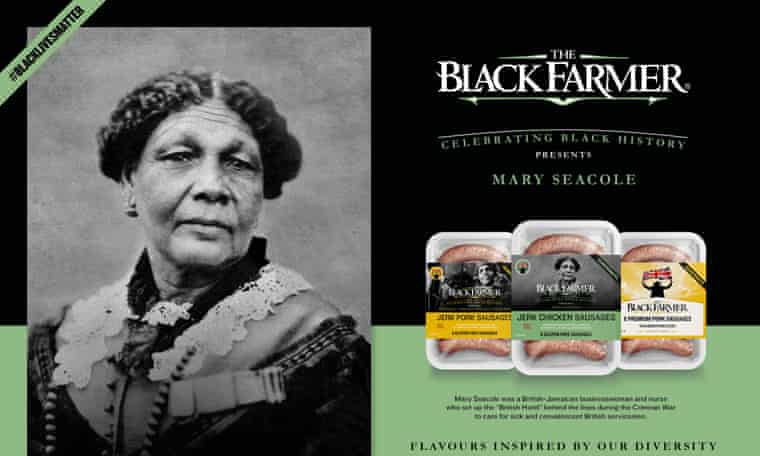

British farmer Wilfred Emmanuel-Jones says supermarkets will now sell his new range of sausages featuring the faces of Mary Seacole and others during Black History Month

by James TapperFrom Robertson’s marmalade to Uncle Ben’s rice, the history of images of black people on British products is long and inglorious.

That is set to change next month when Mary Seacole, the British-Jamaican nurse who cared for soldiers during the Crimean war, will become one of three black heroes from British history to be featured on supermarket shelves.

The Black Farmer brand – created by Wilfred Emmanuel-Jones, who believes he is Britain’s only black farmer – will launch a range of sausages featuring the faces of Seacole as well as George Arthur Roberts, a first world war veteran and civil rights campaigner, and Lincoln Orville Lynch, an RAF air gunner decorated for his distinguished service in the second world war.

In what Emmanuel-Jones says is another first, every major supermarket will devote end-of-aisle promotional space to the brands in support of Black History Month, with all proceeds going to support two black charities, the Black Cultural Archives and the Mary Seacole Trust.

“With the Black Lives Matter movement, I felt I had a responsibility,” he told the Observer. “I’m the only person of colour around that is in a position to challenge all the big retailers in the food industry. When I go into a head office, I can guarantee you that I’m going to be the only person of colour. That is unacceptable. People in my industry need to be made accountable, not just about profits for shareholders but also the people of colour who are buying their products.”

Emmanuel-Jones, 63, arrived in Britain aged three from Jamaica as part of the Windrush generation and grew up in Birmingham. After a career in food marketing, he bought a small farm – “it’s not until you own land that you really belong,” he said – and launched the Black Farmer brand.

When the Black Lives Matter protests seemed to be forcing some changes in the US and in Britain, Emmanuel-Jones wrote to the chief executives of all the supermarket chains calling on them to act. British firms have a poor record on celebrating Black History Month, unlike in America, he said.

He has managed to persuade Marks & Spencer, Tesco, Sainsbury’s, Asda, Morrisons, Co-op, Aldi, Lidl, Waitrose, Budgen’s and Ocado to devote in-store promotional space to the month-long campaign for the pork jerk and chicken jerk sausages.

“It was a fight,” he said. “Co-op and Sainsbury’s were the first to say ‘actually we want to support that’. Others came through begrudgingly and others refused initially. I went back to them and I was quite vicious. I told them ‘this is about the greater good, actually for once in your life prioritising diversity. And the only reason I was able to do that was because I’m not answerable to anybody.”

Emmanuel-Jones, who stood as a Conservative parliamentary candidate in 2010 and believes his party needs to do more to combat racism, said the choice of sausages was very deliberate. “People didn’t get it – ‘why is a black guy doing sausages?’ I wanted to be categorised as a British brand not an ethnic brand.”

He said the initial refusal by some of the chains demonstrated why they needed greater diversity in the workforce. “One said no because jerk is not an autumn flavour,” he said. “I said ‘jerk is from the Caribbean – we’re celebrating black people’. Another said ‘we’ll just take the pork’. But some people in the black community do not eat pork. One of the reasons Black Lives Matter has happened is because they don’t have people in their organisation who understand – you come across naivety like this.”

Although Emmanuel-Jones believes he is the UK’s only black farmer, others in the food industry have spoken out about a lack of action in the sector. Philip Udeh of Füd, the energy drink startup, suggested in June that retailers could adopt the same approach as the French cosmetics company Sephora, which has pledged to take at least 15% of its stock from black-owned businesses.

Trevor Robinson, the founder of the Quiet Storm advertising agency, said that there were very few black figures who had been used in advertising or marketing, with the exception of Howard Brown, who starred in commercials for Halifax until 2008.

“I can’t think of too many people of colour who’ve been used successfully outside the Halifax man,” Robinson said. “Ikea did a grime track that was used for their ads. Nike has been good at tapping into black culture and I think that’s really powerful and they’ve done it incredibly sensitively.”

Robinson said he no longer needed to have so many “uncomfortable conversations” with his clients about reflecting the diversity in their advertising.

“But even brands like Benetton – it’s now used as a derogatory term ‘are you trying to make that into a Benetton ad?’ The fact it’s been championed by some brands is not enough. And that really changes when you get more people of colour within companies.”

Marketing racial stereotypes

Robertson’s marmalade

For 91 years, Robertson’s featured a “golliwog” picture on it jam jars. Robertson’s promoted the dolls, dressed in minstrel-style outfits, until the early 1980s. The company renamed the character as “Golly” and carried on using the logo on its labels until 2001.

Aunt Jemima

She was a logo of one of America’s most popular pancake and syrup products for 130 years. The character, a woman in a headscarf, was a stereotypical “mammy” and Quaker Foods did nothing until the rise of Black Lives Matter.

Uncle Ben’s rice

Uncle Ben, another bow-tied, smiling black-faced logo, was invented in the 1940s and was on packets of the Mars-owned brand until June this year.