Floating Spaceports For Future Rockets

by Tom NardiWhile early prototypes for SpaceX’s Starship have been exploding fairly regularly at the company’s Texas test facility, the overall program has been moving forward at a terrific pace. The towering spacecraft, which CEO Elon Musk believes will be the key to building a sustainable human colony on Mars, has gone from CGI rendering to flight hardware in just a few short years. That’s fast even by conventional rocket terms, but then, there’s little about Starship that anyone would dare call conventional.

Nearly every component of the deep space vehicle is either a technological leap forward or a deviation from the norm. Its revolutionary full-flow staged combustion engines, the first of their kind to ever fly, are so complex that the rest of the aerospace industry gave up trying to build them decades ago. To support rapid reusability, Starship’s sleek fuselage abandons finicky carbon fiber for much hardier (and heavier) stainless steel; a material that hasn’t been used to build a rocket since the dawn of the Space Age.

Then there’s the sheer size of it: when Starship is mounted atop its matching Super Heavy booster, it will be taller and heavier than both the iconic Saturn V and NASA’s upcoming Space Launch System. At liftoff the booster’s 31 Raptor engines will produce an incredible 16,000,000 pounds of thrust, unleashing a fearsome pressure wave on the ground that would literally be fatal for anyone who got too close.

Which leads to an interesting question: where could you safely launch (and land) such a massive rocket? Even under ideal circumstances you would need to keep people several kilometers away from the pad, but what if the worst should happen? It’s one thing if a single-engine prototype goes up in flames, but should a fully fueled Starship stack explode on the pad, the resulting fireball would have the equivalent energy of several kilotons of TNT.

Thanks to the stream of consciousness that Elon often unloads on Twitter, we might have our answer. While responding to a comment about past efforts to launch orbital rockets from the ocean, he casually mentioned that Starship would likely operate from floating spaceports once it started flying regularly:

While history cautions us against looking too deeply into Elon’s social media comments, the potential advantages to launching Starship from the ocean are a bit too much to dismiss out of hand. Especially since it’s a proven technology: the Zenit rocket he references made more than 30 successful orbital launches from its unique floating pad.

Last of the Soviet Rockets

Developed in the 1980s, the Zenit rocket was intended to replace the aging Soyuz and Proton launchers that were the backbone of the Soviet space program. Similar in size and specifications to the early versions of SpaceX’s Falcon 9, the liquid oxygen and refined kerosene powered Zenit would be cheaper and safer to operate than its predecessors. Its ability to act as a strap-on booster for larger vehicles, another similarity shared with the Falcon 9, also promised to further streamline space logistics for the USSR.

Of course, that never happened. Before all the bugs could be worked out of the new booster the Soviet Union collapsed, and the program became mired in politics. Not only did the Russian Federation lack the funds to simultaneously operate the Soyuz, Proton, and Zenit to their full potential, but there was concern about launching sensitive payloads on a rocket that was now being manufactured in the newly independent Ukraine. After several high profile failures in the 1990s, the Zenit program was very nearly cancelled entirely.

One if By Land, Two if By Sea

While the dissolution of the Soviet Union ultimately kept the Zenit from replacing the Soyuz and Proton, it also provided some tantalizing businesses possibilities. With the Cold War officially over, an international coalition of companies from the United States, Russia, Ukraine, and Norway was formed to offer Zenit to commercial customers. Rather than having to decide which nation would serve as the rocket’s permanent home base, a modified version of the vehicle would fly from a self-propelled oceangoing launch pad that started life as an offshore oil rig. This revolutionary new service was called, aptly enough, Sea Launch.

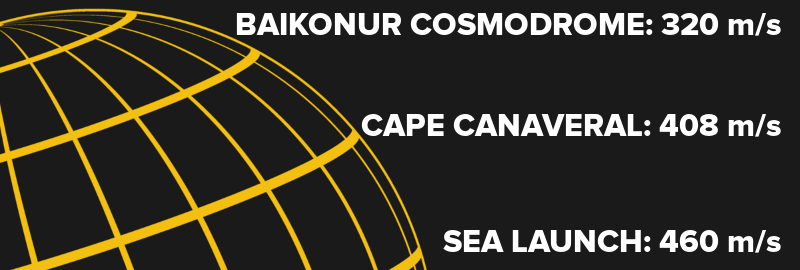

Beyond the political aspect of not being tied to any one nation, launching from the ocean offered a number of compelling advantages. For one, it was much safer should the rocket explode on the pad or fail shortly after liftoff. This was especially important given the somewhat spotty track record of the Zenit. It would also allow launches from near the Earth’s equator, which imparts greater tangential velocity on the vehicle during ascent and directly translates into increased payload capacity.

The initial boost provided by the Earth’s rotation can be approximated by taking the planet’s rotational speed at the equator and multiplying it by the cosine of the launch site’s latitude:

While the gains offered by equatorial sea launch might seem small compared to orbital velocity (roughly 28,000 km/h), the rocket equation is exceptionally unforgiving. Even a tiny reduction in the acceleration required to reach orbit allows more of the vehicle’s mass to be devoted to payload instead of propellant. Additionally, it means that payloads destined for equatorial orbits, such as geosynchronous communication satellites, don’t need to adjust their inclination after separation from the booster. This further reduces propellant requirements and gets the satellite into its final operational orbit faster, which results in a longer useful lifetime.

An Experiment Cut Short

In total 36 Zenit rockets were launched from Sea Launch’s floating pad between 1999 and 2014, 32 of which successfully delivered their payloads to orbit. The most serious failure was in January 2007, when the rocket carrying the NSS-8 satellite failed a few seconds after ignition and engulfed the launchpad in a fireball.

Due to the design of the floating launchpad, the faltering rocket fell through an opening in the platform and sunk; causing only superficial damage to the infrastructure aboard. As part of normal operating procedure, no personnel were aboard the Ocean Odyssey platform at the time of the launch, so no injuries were sustained. The platform was repaired and ready for its next launch just six months after the incident.

From a technical standpoint, Sea Launch showed there was definite promise for ocean-launched orbital rockets. The handful of failures experienced by the program were in no way related to the logistics of transporting the rocket to the equator or the unique nature of the floating launchpad. Nor was the single failure aboard Ocean Odyssey enough to delay the program for very long, much less stop it entirely. If anything, the NSS-8 explosion demonstrated the inherent safety of ocean launches in the event of a catastrophic failure.

Unfortunately, Sea Launch was eventually killed by the same thing that made it possible in the first place: political turmoil. The 2014 annexation of Crimea by Russia strained the country’s relationship with Ukraine, and while publicly Sea Launch denied the situation had any impact on their operation, within a few months the staff were laid off and the Ocean Odyssey and its support ship were mothballed.

Rockets On the High Seas

SpaceX has already gained considerable experience landing their rockets on floating platforms, which arguably, is a harder feat than lifting off from one. The Sea Launch project proved beyond a shadow of a doubt the concept worked, it just needs to be scaled up. As Elon pointed out, Starship and the Super Heavy booster are a far larger vehicle than Zenit, but that doesn’t mean the core technology would need to be any different.

The overall Starship architecture is built around the concept of orbital refueling, which means each mission will actually consist of multiple launches in quick succession. Up to five or six in the case of a trip to Mars, all launched within a few days of each other.

Equatorial sea launches would help streamline this process as much as possible, allowing the maximum amount of propellant to be delivered to the Starship waiting in orbit in the least amount of time. The per-flight gains won’t be much, but SpaceX is clearly playing the long game. At the very least, it would help keep the incredible amount of noise such an operation would produce as far away from civilization as possible.

Or, as we’ve learned with SpaceX in the past, it might never happen. Perhaps the cost of building a fleet of gargantuan floating spaceports will end up being so high as to negate any advantages gained from ocean launches. With all the changes the Starship design has undergone in just a few short years, very little about this futuristic craft can be said with absolute certainty. Many doubted it would ever even get this far.

But even if SpaceX doesn’t go forward with launching Starship from the ocean, there’s still hope for the concept of ocean-going rocketry. The Russian space agency Roscosmos has announced they plan on getting the languishing Ocean Odyssey up and running again, this time using only domestic technology. Just like stainless steel rockets, it seems that ocean launchpads are coming back in style for the New Space Race.