How to Send a File

My new book, How To: Absurd Scientific Advice for Common Real-World Problems, comes out in a week! You can preorder it now on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, IndieBound, and Apple Books.

Here’s an excerpt from the How To chapter on file transfers.

Chapter 19: How to Send a File

Sending large data files can be difficult.

Modern software systems have moved away from the concept of “files.” They don’t show you a folder full of image files; they show you a collection of photos. But files linger on, and will probably continue to do so for decades to come. And as long as we have files, we’ll need to send them to people.

The simplest, most obvious way to send a file is to pick up the device the file is stored on, walk over to the intended recipient, and hand it to them.

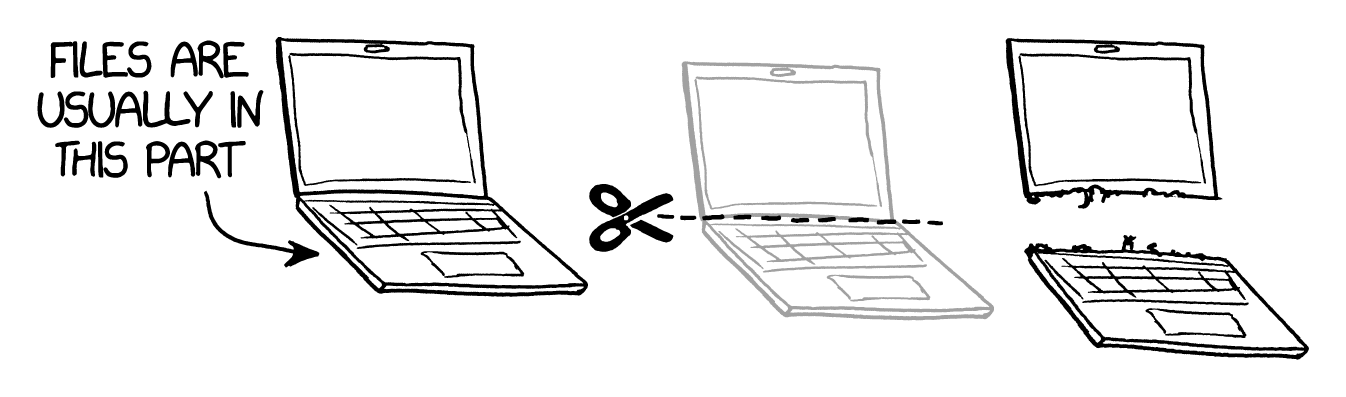

Carrying computers can be difficult — especially the earlier ones that were the size of a whole room — so rather than carry the whole computer, you can try detaching a piece of the computer containing the file. You can then bring this piece to the other person and let them transfer it to their own device. On a desktop-style computer, the files may be stored on a hard drive, which can often be removed without destroying the computer.

On some devices, though, file storage is permanently attached to the electronics, making removal more challenging.

A more convenient and less destructive solution is removable storage. You can make a copy of the file, put it on a device, then give the device to the person.

Carrying storage devices around is a surprisingly high-bandwidth way to transfer information. A suitcase full of MicroSD cards contains many petabytes of data; if you want to transfer very large amounts of data, mailing boxes of disk drives will almost always be faster than transferring them over the internet.

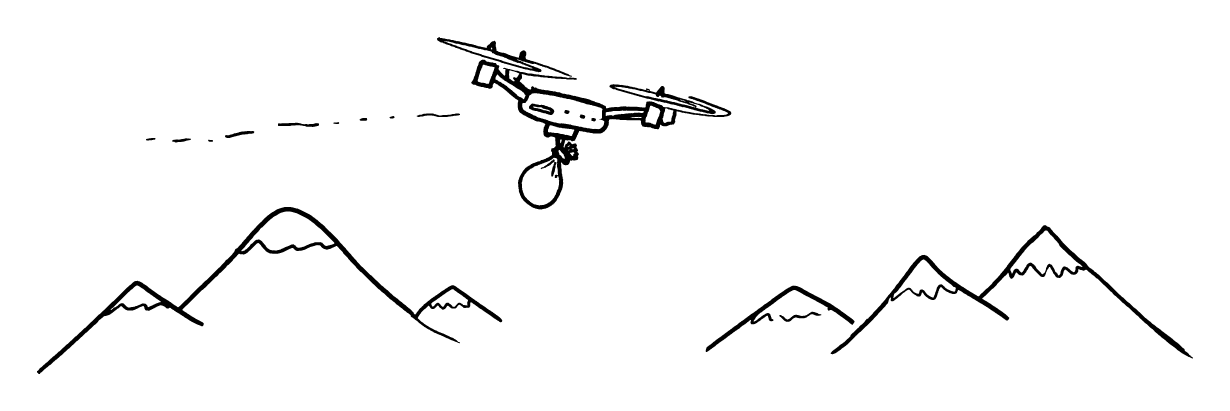

If you want to send data to a specific location that’s too far to walk, but not convenient to reach by mail — say, a nearby mountaintop — you could try using some kind of autonomous vehicle to carry it. A delivery drone, for example, could easily carry a small satchel of SD cards containing terabytes of data.

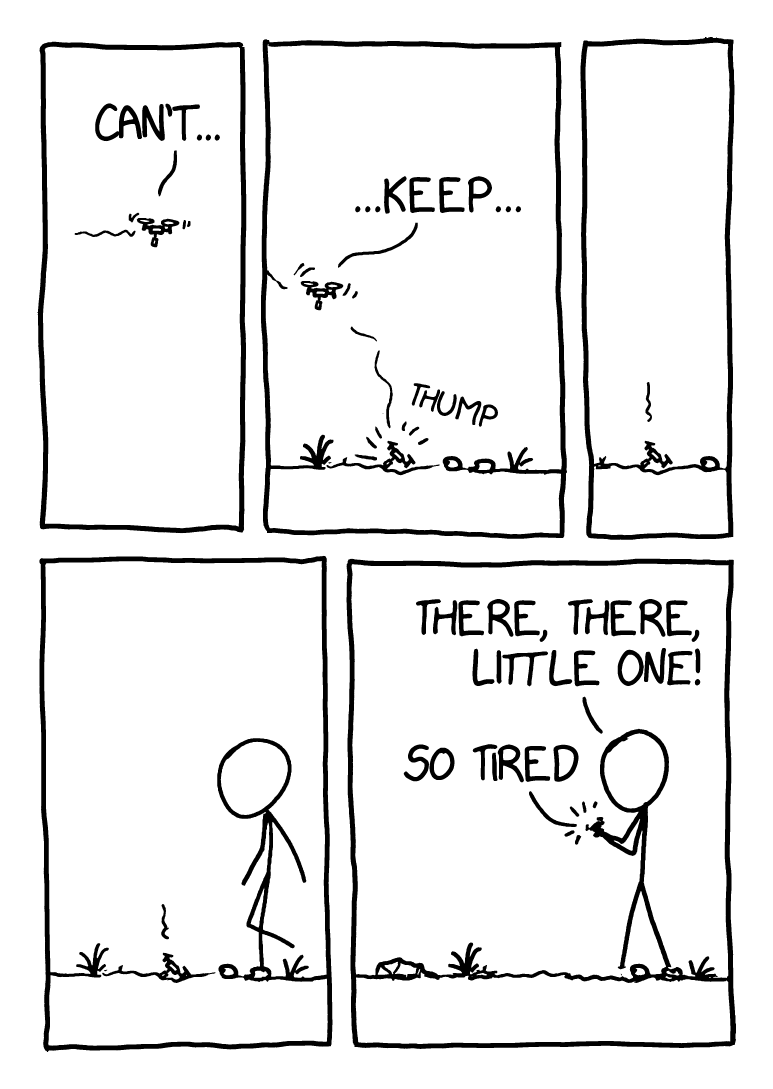

Quadcopter-style drones don’t work very well over long distances thanks to the limitations of batteries. If a drone has to carry its own battery, it can only hover for so long. If it wants to hover longer, it needs to carry a bigger battery, but that means more weight and faster power consumption. For the same reason that a house supported by jet engines [Note: For more on hovering houses, see Chapter 7: How to Move] can only hover for a few hours, small coaster-size drones typically have flight times measured in minutes, and the larger ones used for photography are usually limited to less than an hour in the air. Even if it flew very fast, a tiny drone carrying a MicroSD card could make it just a few miles before running out of steam.

You could increase your range by making the drone bigger, adding solar panels, flying higher, and going faster. Or you could turn to the real masters of efficient long-distance flight:

Butterflies.

Monarch butterflies travel thousands of miles during their migration across North America, with some traveling all the way from Canada to Mexico in a single season. If you look up during the spring or fall on the East Coast of the United States, you can sometimes spot them gliding by silently overhead, a few hundred feet above the ground. Their extreme range puts drones — and even many large aircraft — to shame.

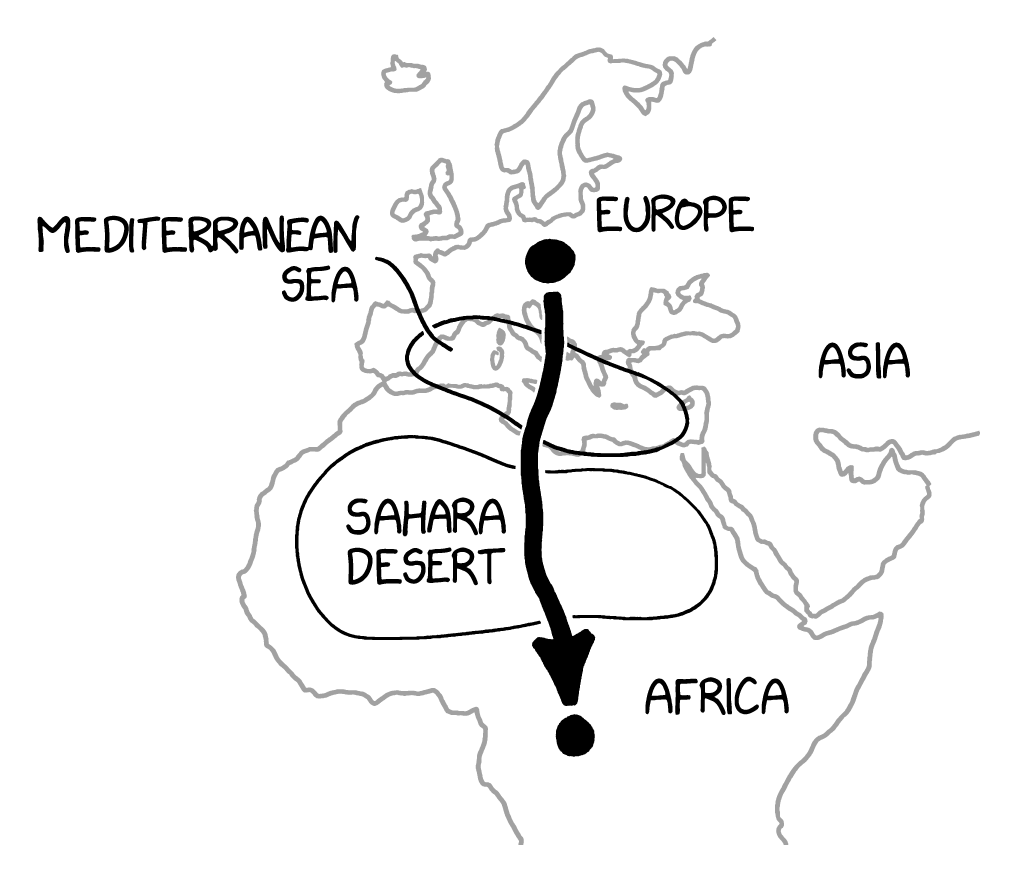

You might think butterflies have an unfair advantage over battery-powered aerial vehicles, since they can stop to consume nectar and “recharge.” Butterflies will certainly refuel if they can, but they don’t necessarily need to. Another butterfly species, the painted lady (Vanessa cardui), is even more impressive: it flies from Europe to central Africa, a 4,000-kilometer flight that takes it over the Mediterranean Sea and the Sahara desert.

Butterflies make these journeys powered only by small reserves of stored lipids. They can fly so much more efficiently than drones in part by soaring — they seek out thermal columns and mountain waves, then hold their wings steady and ride the rising air upward like a vulture, hawk, or eagle.

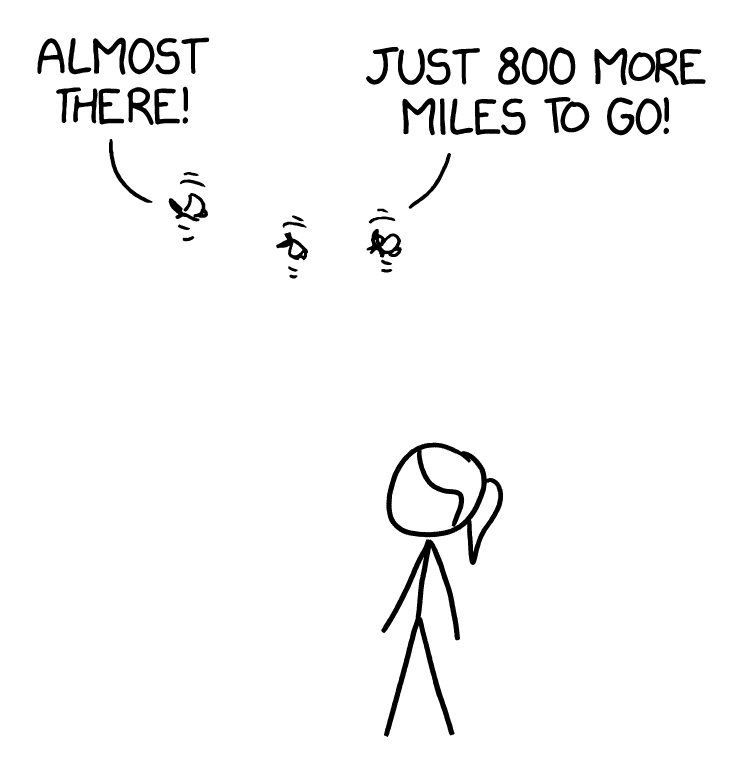

If you want to send your file to someone who lives along the migration route, could you get a butterfly to carry it for you?

Butterflies can carry weights. Volunteers with groups like Monarch Watch tag tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands of monarch butterflies each year to track their migration and monitor their population (which has been in decline in recent decades). The smaller tags weigh about a milligram, but monarchs have completed their migration with larger tags that weigh 10 mg or more.

MicroSD cards weigh several hundred milligrams — comparable to the weight of a butterfly — so butterflies would have a hard time carrying them. But there’s no reason a storage device can’t be made smaller. MicroSD cards contain memory chips, and the storage density of these chips might be up to a gigabyte per square millimeter. Given those sizes, a butterfly could easily carry a tiny chip with a gigabyte of data. If your file is larger than that, you could break it up across multiple butterflies, and send multiple copies for redundancy.

When your data finally arrived at its destination, the recipient would have to check a lot of butterflies to assemble all the pieces of the file. You may need to develop some kind of touchless butterfly scanner that allows them to scan many butterflies at once.

You could avoid that problem — and increase your bandwidth dramatically — by using DNA-based storage. Researchers have stored data by encoding it into a DNA sample, then sequencing the DNA to recover it. Systems like this can achieve densities far beyond anything we do with chips — it’s possible to store and recover hundreds of petabytes of data using a single gram of DNA.

Each year, tens to hundreds of millions of monarch butterflies arrive in Mexico to spend the winter together in giant colonies in the mountains. If you tagged ten million of these butterflies with tiny pouches containing 5 mg of DNA storage each, the total capacity of the butterfly armada would be about 10 zettabytes — 10,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 bytes. That’s roughly the total amount of digital data in existence in the late 2010s.

If the Sun is warm, the winds are favorable, and it’s the right time of year, you could use butterflies to send someone the entire internet.

How To: Absurd Scientific Advice for Common Real-World Problems will be released on September 3rd. You can preorder it now on Amazon, Barnes & Noble, IndieBound, and Apple Books.