Amateur Air Pollution Trackers Are Mapping Western Wildfire Smoke

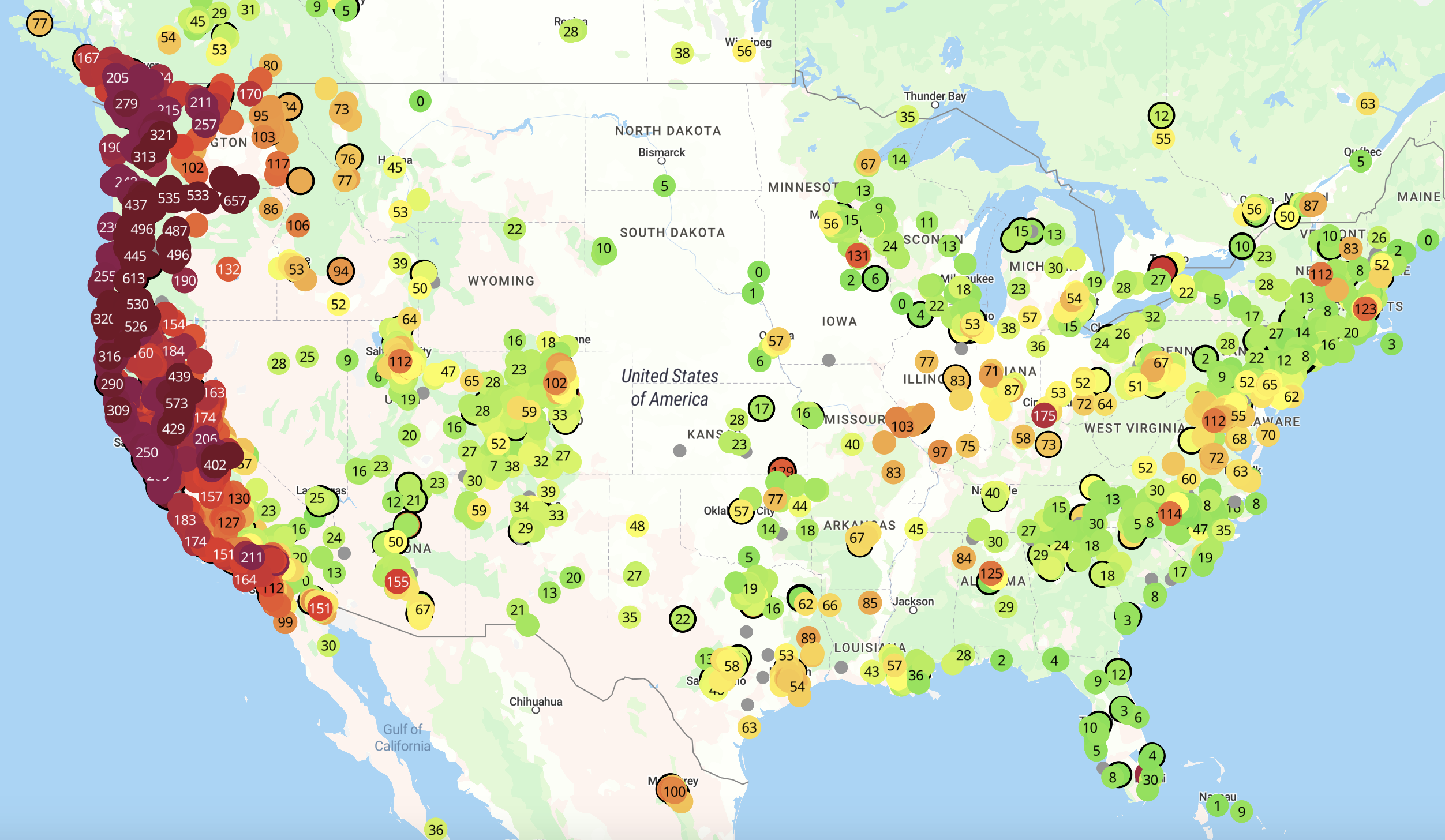

Using thousands of PurpleAir sensors, a community of tech enthusiasts and health-conscious residents are capturing a real-time portrait of an environmental crisis.

by Laura BlissIn late 2018, as smoke from the Camp Fire engulfed the Bay Area for days on end, Nina Lewis bought a PurpleAir sensor. For about $250, the small WiFi-equipped air pollution monitor allowed her to track the air quality index, or AQI, as well as particulate matter levels in real time outside her home near San Mateo, California.

Compared to readings from the closest government air monitor nine miles away, the sensor gave Lewis a clearer picture of how much pollution was affecting her local surroundings, informing her about things like whether to wash the car or take the dog for a walk. She thought her neighbors might also appreciate that data, which populates a free public map of global PurpleAir sensors. But she didn’t realize how dependent others had become until the day her husband unplugged the device to mow the lawn.

“A guy popped up on Nextdoor, asking me what had happened to the PurpleAir monitor,” said Lewis, who works as a computer security manager at Oracle. “It turned out people were looking.”

People really are looking, and now more than ever before. As catastrophic wildfires in California, Oregon and Washington consume millions of acres, decimate communities, and claim dozens of lives, much of the Western U.S. is again shrouded in awful smoke. On September 13, the air quality in Portland ranked as the world’s worst for the fourth consecutive day, and pollution in California continued to press into the unhealthy range. Traffic to PurpleAir’s online map has jumped 1,000% from average, with about 500,000 daily hits from California alone last week, says the company’s CEO and founder Adrian Dybwad. Sales of the devices, which range from $200 to $290, have jumped, as well.

The Environmental Protection Agency also runs a public air quality map called AirNow, which is fed by a network of regulatory-grade monitors that directly measure a wide range of air pollutants. PurpleAir sensors measure fewer types, and rely on lasers to count pollutants indirectly. While government equipment is more accurate and less prone to user error, its coverage is not as widespread in many areas, nor does it update as frequently as PurpleAir — hence the surge in public interest, and the fact that the EPA and the U.S. Forest Service recently rolled out a new fire smoke map that blends government data with low-cost sensor readings, including from PurpleAir.

The attention to the PurpleAir map also spotlights the people who are producing it, like Lewis. There are now over 9,000 global sensors plugged into the public PurpleAir network, with the vast majority owned and managed by private individuals, according to Dybwad. That includes a strong contingent of self-described computer nerds who have combined a fascination with data and gadgetry with a certain level of interest in their communities, as well as in the community that they themselves form.

“It’s a very tight-knit, supportive group, from my experience,” said Benjamin Clark, a public policy and planning professor at the University of Oregon who has researched how citizen science can drive government decisions, including with respect to air quality. “People are pretty passionate about the device itself and the information it can produce.” PurpleAir is a good example of how crowdsourced data can be useful to policymakers. Sometimes, “a group of five novices can do as well as one expert,” he said.

In a Facebook group of about 1,200 global members, PurpleAir users post screenshots and photos of AQI readings, work through installation hiccups and share updates from their daily air monitoring. Some turn their efforts into larger projects: Analytical minds share GitHub repositories and debate conversion factors to compare their findings to EPA data. Hacker types discuss how to solder extra wires, upgrade circuit boards, and connect sensors to smart home devices. The company’s pro-social, DIY philosophy — somewhat unusual for the technology industry — encourages such tinkering, and Dybwad sometimes responds to comments himself.

It’s something of a ham radio network of the 21st century, several members said. Like those amateur shortwave radio operators, who tap into official emergency communication lines to assist in calamity, PurpleAir owners are “at the ready in the event of a disaster, supplying data for everyone to view,” said Gary Brickley, a retired union stagehand who runs a PurpleAir sensor and weather station from his hilltop home in San Francisco. There is a fair amount of overlap between the two worlds: Several air quality trackers are also hams, including Dave Pacek, a retired Air Force intelligence analyst who runs a PurpleAir sensor (as well as a seismometer) at his Sacramento home.

“We nerdy types really do get into some strange stuff,” he said, calling the Facebook group a valuable way to interact with fellow PurpleAir enthusiasts and Dybwad himself for “troubleshooting, suggestions for future design features, etc.”

Not everyone in the Facebook group is technically minded. Many, if not most, buy the sensors because they’re concerned about what they’re breathing, not because they enjoy fiddling with circuit boards. Several members remarked that they appreciate that the devices are simple to set up. Ashley Froehlich got her first monitor after the 2017 Northern California wine country fires, which produced smoke so thick it was visible inside her own home. Real-time readings from her indoor and outdoor PurpleAir devices let her make minute-by-minute decisions for managing her health — for example, when the AQI inside her home surpasses 200, she’ll go upstairs, where the indoor air tends to be clearer. “It’s so anxiety-inducing to not know how bad it really is and just rely on what you can see outdoors,” she said, referring to the government’s network of sensors.

That PurpleAir’s sales are taking off because of an environmental tragedy of unprecedented scale — one that is symptomatic of an even larger global crisis — is not something that Dybwad is proud of. But the ability to serve information to people who need it is. In addition to internet traffic and a flurry of activity in the Facebook group, PurpleAir staff have received a surge of phone calls from throughout the Western U.S., with worried callers wondering what the red and purple colors mean and what they should do about it.

While PurpleAir doesn’t advise anyone on how to respond to the data, “we do provide an outlet because people are feeling desperate,” Dybwad said. “The EPA won’t answer them, the air quality district is rarely easy to call, so they call us because there’s a number on our website. They often leave feeling more assured.”

While the public map makes PurpleAir unique among commercial-grade air quality monitors, it is not the only kind on the market. Plume Labs, Aclima, and Temtop make related products. The data generated by such devices can also help inform government decisions about where to place clean air shelters or how to notify certain communities to stay indoors, Clark said.

But what about for the parts of the world that lack the benefits of low-cost, distributed air quality monitors? For example, Birmingham, Alabama’s metro area recently ranked the 14th-most polluted U.S. city for year-round particle pollution. But there are only three PurpleAir sensors in the region, plus one EPA sensor near an industrial site on the outskirts, according to the AirNow map. And while PurpleAir sensors abound in the tech haven of the San Francisco Bay Area, there are far fewer throughout California’s Central Valley, where asthma rates are among the highest in the U.S.

Clark’s research has found steady predictors of where PurpleAir sensors tend to be located: In the Western U.S. as well as parts of the South, the wealthier and whiter the community, the more air monitors there are likely to be, leaving a data gap in many poorer communities and communities of color. That’s an environmental justice problem, Clark said, since those places are more likely to be exposed to hazardous air in the first place. “Technology can enhance good decision-making, but only if it’s distributed across all parts of the population,” he said. Nor can technology substitute for engaged citizenship, as a New York Times op-ed praising PurpleAir’s community-centered approach pointed out earlier this month.

Dybwad is hopeful that partnerships with nonprofit organizations, universities, and government authorities, including the EPA as well as local regulators, could help fill in blank spots. For example, in Lane County, Oregon, where fog and smoke from the massive Holiday Farm wildfire reduced visibility to near zero on Sunday, the regional air pollution agency has been installing PurpleAir sensors outside schools, parks and neighborhood settings since 2017 to improve public monitoring efforts. Environmental justice groups have also amplified pollution monitoring in low-income areas near highways, industry and agriculture in pockets around the U.S.

In the meantime, the proliferation of devices, mostly privately owned, is keeping countless others informed as smoke chokes the skies in the Pacific Northwest and California. Lately, Lewis has been studying the PurpleAir map to suss out how far she’d have to travel to escape the toxic air. “Everyone is interested in whether the air outside is decent to breathe,” she said. “Right now, the only place to really go is Canada.”