Banks aren’t dealing with financial abuse. Monzo has an answer

Reports of financial and economic abuse have risen during the pandemic – and banks need to be better at dealing with the problem

by Joshua Zitser

Her husband wasn’t turning up to work. Meanwhile, Leslie* was the family’s main earner who was working hard to pay for his lavish lifestyle. As she kept their joint bank account topped up, he spent a large chunk of her money on designer suits and trips abroad with other women.

A couple of years into their marriage, Leslie became concerned about the way her husband was abusing their joint account. And then there was the physical abuse. “As long as I was able to provide the lifestyle that he wanted, the physical punishment wasn’t as bad,” she says.

Leslie struggled to find a safe way to inform the bank of what was happening. “I asked why they didn’t notice that every month for years, the only person who had been putting money in was me but they allowed him to take out a lump payment of several thousand pounds?” Despite the pleas for help, her abuser continued spending. He set up a joint credit card without her consent and took out loans on her behalf. “All that time, the banks weren’t willing to listen,” she says.

Leslie was a victim of financial and economic abuse, which became a major feature of her 15-year relationship which eventually ended in 2017. The type of abuse is growing and financial institutions haven’t done enough to tackle its problems.

Charity Women’s Aid describes financial abuse as a “perpetrator using or misusing money which limits and controls their partner’s current and future actions and their freedom of choice.” It falls under the broader definition of economic abuse, a phrase often used interchangeably, which is designed to “reinforce or create economic instability” in relationships.

It is an extremely common form of domestic abuse, used to control and degrade survivors. According to the charity Surviving Economic Abuse, 95 per cent of people who experience domestic abuse – an estimated 2.4 million adults a year in the UK – are also experiencing some form of economic abuse. The charity also claims that one in five British women have experienced financial abuse in a current or former relationship.

Leslie’s story, a particularly harrowing tale, includes a number of ways in which economic abuse can manifest itself; putting debt in a partner’s name, stealing money and setting up joint credit cards without consent. They’re not the only ways this form of abuse can happen though. It can often involve insisting benefits are put down in the abuser’s name, restricting access to essential resources or deliberately damaging property belonging to the survivor.

During the pandemic, the situation appears to have worsened. “To us, it’s quite clear that under Covid-19 it is simply getting worse,” says Christine Govier, the head of Surviving Economic Abuse’s specialist economic abuse team. Govier adds the charity has seen an increased number of calls to its helplines and people contacting its support services. Women’s Aid agrees – the picture of financial abuse during the spread of coronavirus is intensifying. According to its April survey of 293 survivors, almost a third of respondents reported their abuser blaming them for the economic impact of the pandemic on their household.

Lockdown measures have also removed some of the opportunities victims might traditionally make use of to escape financial abuse. “The pandemic hasn't made abusers worse but it has closed down opportunities for victims and survivors to access support discreetly. It’s harder to use the phone if your abuser is at home all day,” says Christine Govier.

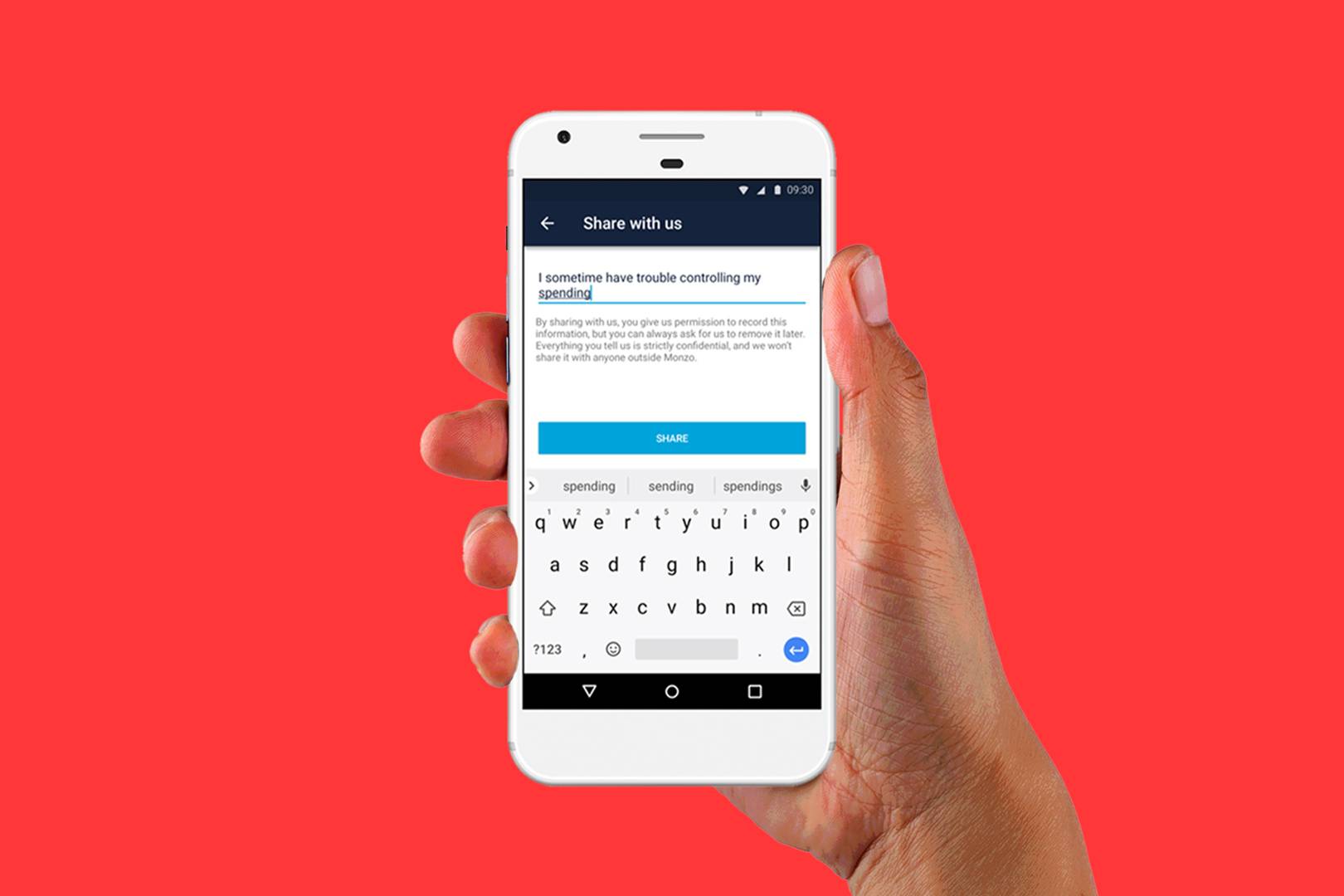

In response, banks are increasingly using technology to try and identify victims of financial abuse and to help set up new avenues for them to seek help. When WIRED spoke to a number of survivors, app-based bank Monzo was mentioned numerous times for its efforts. Unlike any other bank, Monzo has introduced a technological tool designed with survivors in mind – in-app traceless messaging. The trailless “share with us”’ feature allows customers to discreetly notify the bank of their situation or to raise concern over any particular transactions. This means no phone calls are required. Since 2018, the feature has been used 2,500 times.

There’s also an option to create a ‘code word’ to alert the police. Customers can set up a phrase privately with Monzo, such as “my chip and pin is broken”, to alert the emergency services on the survivor’s behalf. The process is designed to appear inconspicuous so not to alert potential abusers to the activity being reported.

Whilst financial and economic abuse primarily affects women, some men and non-binary individuals also rely on the banks’ new technology to seek support. Michael*, a 25-year-old from London, used Monzo whilst in a coercive situation. “In a moment of desperation, I used the in-app messaging feature. I was kind of astonished and incredibly impressed that almost immediately I was contacted by a support worker who told me they were sorry I was going through a tough time and they wanted to know if there was any way that they could help.”

Following this, a specialist customer support worker put Michael in touch with a helpline and a domestic abuse charity. Monzo’s vulnerability manager, Natalie Ledward, says the firm has a “specialist vulnerable customer team who are trained to spot signs of abuse”. The team is currently made up of 20 trained specialists.

Other banks are also using highly-trained customer support workers to identify and assist survivors and victims but have not adopted such technical measures. In 2019, Lloyds, Halifax and Bank of Scotland – all part of the Lloyds Banking Group – launched their ‘Domestic and Financial Abuse Team’. The service assists customers with financial guidance and redirects them to specialist charities for emotional support.

The importance of having specifically trained staff at banks is a major focus for abuse charities. “It is crucial that frontline staff have a clear understanding of how to recognise and respond to coercive control – including economic abuse – and of the importance of ensuring survivors’ safety,” says Sophie Francis-Cansfield, senior campaigns and policy officer at Women’s Aid.

Whilst not all banks have specially-designed schemes for economic abuse survivors, such as Monzo and Lloyds, most major banks have signed up for a voluntary code of practice to support victims. The code commits banking organisations to “raising awareness, training colleagues and introducing other initiatives to help victims regain more control over their finances”. Initiated by Finance UK, Santander, HSBC and Nationwide have signed up.

But Women’s Aid is urging banks to go further by adopting and implementing more specific policies for abuse survivors. “This could include flagging survivors’ accounts and providing them with a named contact for support, treating bank accounts separately, freezing joint accounts quickly and preventing further abuse,” their spokesperson says.

Whilst there are still concerns about how the banks currently address economic abuse, the banking sector is said to be seeking innovative ways to identify victims and to help them overcome their difficulties. They’re turning to AI.

In March, the Financial Conduct Authority and the Bank of England established a forum to discuss the use of artificial intelligence in financial services. This followed a February 2020 study, from the Centre for Economic Performance (CEP) at LSE, which explored how machine-learning might be used to recognise those at high risk of domestic and financial abuse. Machine-learning could be used to analyse existing information, such as existing criminal records, calls made to the police and reported incidents of violence, to more effectively identify the risk of repeat incidents or patterns of abuse.

New technologies are presenting emerging opportunities for some survivors to seek help from their banks, but specific policies are seeing not being implemented widely. As for Leslie, however, she is cautiously optimistic about the future. “I think, nowadays, the banks might have noticed what I was going through even if I didn’t recognise it myself”, she says.

*Names have been changed

More great stories from WIRED

💾 Inside the secret plan to reboot Isis from a huge digital backup

⌚ Your Apple Watch could soon tell you if you’ve got coronavirus. Here's how

🗺️ Fed up of giving your data away? Try these privacy-friendly Google Maps alternatives instead

🔊 Listen to The WIRED Podcast, the week in science, technology and culture, delivered every Friday