The Indian Express

Explained Ideas: As Parliament resumes, why Question Hour matters

Cancelling Question Hour erodes constitutional mandate of parliamentary oversight over executive action, writes P Rajeev.

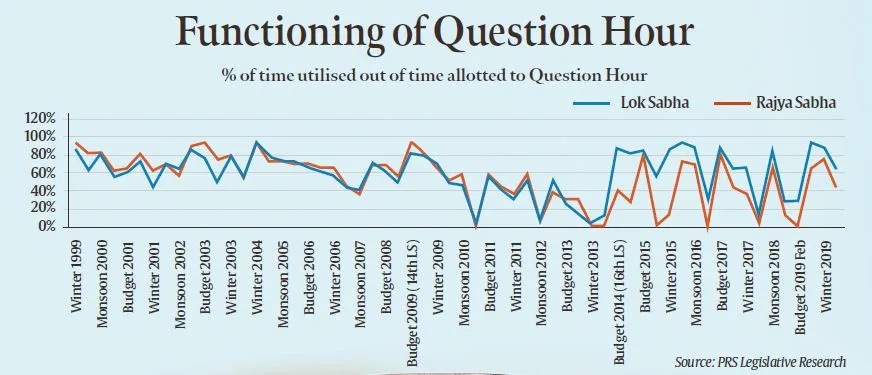

by Explained DeskThe decision to go without “Question Hour” during the Monsoon Session of Parliament, beginning September 14, has evoked serious concerns about the democratic functioning of the institution. Question Hour is not only an opportunity for the members to raise questions, but it is a parliamentary device primarily meant for exercising legislative control over executive actions.

P Rajeev, a former Rajya Sabha MP and a senior CPM leader writes that “the time has come to grill this government on different issues such as its failure in handling the pandemic, the unprecedented decline in GDP and its impact on the economy, the New Education Policy, tensions at the border, rising unemployment, the miseries of migrant labour and so forth”.

The government’s actions erode the constitutional mandate of parliamentary oversight over executive actions as envisaged under Article 75 (3) of the Indian Constitution. “By doing away with the Question Hour, the Modi government has opted for a face-saving measure,” he writes in The Indian Express.

https://images.indianexpress.com/2020/08/1x1.png

The right to question the executive has been exercised by members of the House from the colonial period. The first Legislative Council in British India under the Charter Act, 1853, showed some degree of independence by giving members the power to ask questions to the executive.

Later, the Indian Council Act of 1861 allowed members to elicit information by means of questions. However, it was the Indian Council Act, 1892, which formulated the rules for asking questions including short notice questions.

Explained Ideas | What must India do to counter China?

The next stage of the development of procedures related to questions came up with the framing of rules under the Indian Council Act, 1909, which incorporated provisions for asking supplementary questions by members.

The Montague-Chelmsford reforms brought forth a significant change in 1919 by incorporating a rule that the first hour of every meeting was earmarked for questions. Parliament has continued this tradition.

In 1921, there was another change. The question on which a member desired to have an oral answer, was distinguished by him with an asterisk, a star. This marked the beginning of starred questions.

These are democratic rights members of Parliament have enjoyed even under colonial rule. “The sad part is that this right is being denied to the elected representatives of Independent India, by the present government,” states Rajeev.