Wall Street Economists Channel Powell's Fiscal Vision

With Congress at an impasse over additional Covid-19 aid, I asked economists from the largest Wall Street institutions what a technocratic approach to federal spending would look like.

by Brian Chappatta“This is the time to use the great fiscal power of the United States to do what we can to support the economy and try to get through this.”

Those words came from Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell in late April, about a month after the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act became law. It was one of the clearest examples of a concerted effort by the central bank’s leadership to signal to lawmakers that the unique challenges posed by the coronavirus pandemic — namely, shutting down parts of the economy and encouraging Americans to stay at home — would require the federal government to spend like never before and that such steps to support households and small businesses were the right thing to do.

“Those are going to be key policies that will come with a hefty price tag,” Powell said at the time. “But we would come out of this eventually with a stronger economy and with less long-run damage to the economy.”

Almost five months later, that level-headed assessment no longer resonates on Capitol Hill. Another powerful fiscal relief package, which once looked like a sure-fire political victory for both parties, is now seen as highly unlikely before the November election. Senate Republicans rallied behind a “skinny” proposal estimated at $500 billion to $700 billion, while House Democrats passed a $3.5 trillion package in May. Speaker Nancy Pelosi has said she would settle for a $2.2 trillion bill, while Treasury Secretary Steven Munchin said the Trump administration could get behind a $1.5 trillion initiative. Still, Democratic leaders and the White House broke off negotiations on a compromise more than a month ago.

While politicians squabble over these dollar amounts, the U.S. economy is teetering. The number of Americans filing jobless claims for the first time was unchanged at 884,000 in the week ended Sept. 5, more than the 850,000 expected by economists. Job losses considered permanent reached 3.4 million in August, the highest since 2013. All the while, bankruptcies keep piling up, with off-price department store chain Century 21 Stores, bakery chain Maison Kayser and the owner of New York Sports Clubs among the latest to seek court protection.

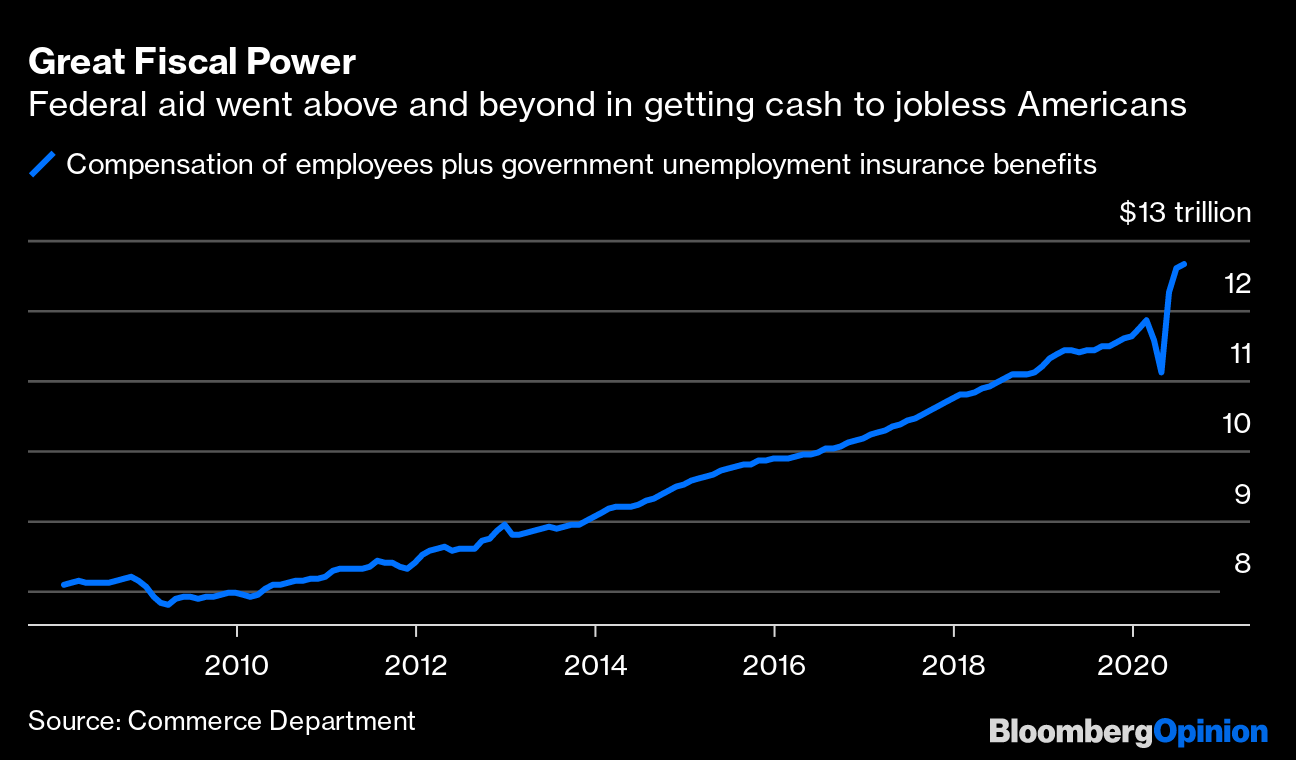

At this point, even supplemental weekly jobless benefit payments authorized by President Donald Trump through executive order at the start of August are starting to dry up. This turn of events has baffled some pragmatists. Why would Congress halt a program that was clearly working? As I’ve noted before, this chart of employee compensation plus unemployment insurance tells the story of why the economy — and the stock market — roared back so quickly:

The simple answer to the conundrum, of course, is that fiscal policy is in the hands of politicians in Congress and not technocrats like Fed officials. The central bank’s leaders certainly haven’t hesitated to talk up the importance of government spending. But, ultimately, it’s out of their control.

So ahead of the Federal Open Market Committee meeting this week, I posed the following hypothetical to economists from the largest Wall Street institutions: If the Federal Reserve were suddenly granted the power of fiscal policy, what would Powell and his colleagues do?

Their full answers are below, but the upshot is this: Free from political considerations, the Fed would most likely send federal funds to strapped state and local governments. The original stimulus proposal from Democrats included $1 trillion in such aid, but Republicans have decried the effort as a way to bail out large cities, which mostly have Democratic mayors, and states like Illinois, New Jersey and Connecticut, with severely underfunded pension plans. The central bank opened a Municipal Liquidity Facility, but only Illinois and New York’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority have used it so far. I’ve written several times that the Fed should do more, but nothing in its toolkit is nearly as effective as outright federal grants.

The Fed would also have a laser-focus on unemployed Americans. It might extend the extra federal unemployment insurance benefits to jobless individuals while also incorporating return-to-work incentives. It could also extend grants to small businesses — under its expanded monetary policy, the central bank is mostly just suppressing borrowing costs for big corporations. Powell has said that by purchasing the debt of AT&T Inc., Apple Inc. and others in the secondary market, it could help avoid job cuts at these companies.

And, lastly, Fed officials have stated time and again that the economic outlook is directly tied to whether the country can contain Covid-19. So a final piece of a Fed fiscal policy would include ample funds for public health initiatives.

Spending on infrastructure received mixed reviews. Additional tax cuts are notably absent from all considerations.

Below are five visions for fiscal policy run by the Fed.

Michael Feroli, chief U.S. economist at JPMorgan Chase & Co.:

“I think it’s pretty clear that if Powell were running fiscal policy he would be delivering more fiscal stimulus than is already being delivered. I think the composition is a little harder to say than the amount, in part because he has avoided commenting too much on specifics. Given the Fed’s concerns about the drag from state and local spending I think it’s safe to say they he would do more to aid state and local governments. I believe he also thinks households need more support, probably through some combination of stimulus checks and extended unemployment benefits.”

Jay Bryson, chief economist at Wells Fargo & Co.:

Fiscal policy makers are politicians, so the packages that they tend to put together reflect the wants of their constituents. So when Republicans are largely in charge of “making the sausage,” fiscal policy changes tend to be biased toward tax cuts. When Democrats are running the sausage factory, spending increases predominate.

Fed officials generally do not make specific recommendations about fiscal policy. They are leery about wading into that political swamp. So it’s difficult to know exactly what they are thinking. FOMC members are not politicians, at least not in the normal sense of the word, so they don’t have “constituents” as fiscal policy makers do. But it seems like the most important objective to committee members right now would be to provide stimulus that affects the economy as quickly as possible.

A policy change that probably WOULD NOT check that box would be a big infrastructure spending package. Infrastructure projects tend to have long implementation lags that would diminish the immediate stimulative effect. Across-the-board tax cuts may or may not get spent quickly (depending on income level and current employment status), so they probably would not be high on that list as well. But enhanced benefits to unemployed workers probably would get spent fairly quickly. Maybe the FOMC would not provide enhanced benefits on the order of $600/week (some members seem to worry a bit about potential disincentive effects on returning to previous low-paying jobs), but some level of enhanced benefits probably would be high on the Fed’s list. I could also see them providing some aid to state and local (S&L) governments. Spending at the S&L level contracted from Q3-2009 through Q4-2012, which exerted headwinds on overall GDP growth during the slow recovery following the Great Recession. With many S&L governments facing large budget deficits today, some aid package for them would reduce the amount of cutbacks that they otherwise will need to make.

Andrew Hollenhorst, chief U.S. economist at Citigroup Inc.:

Let me be clear, it is for good reason that Congress (a democratically elected body) is responsible for fiscal policy and not unelected Fed officials.

Most Fed officials have reflected the same logic as lawmakers — with interest rates low and the unemployment rate elevated there is more risk in doing too little to support the economy than too much. In a hypothetical scenario where Fed officials determined fiscal policy, I expect they would focus on filling the same holes in income — where individuals, businesses and municipalities lost wages and revenue through no fault of their own. This could take various forms including those being currently contemplated by Congress. Similar to the approach to monetary policy, Fed officials might leave in place some amount of fiscal support until, for instance, the unemployment rate returned to a more normal level. But this is a reminder of why it would be problematic for an unelected body to determine fiscal policy. What rules or principles would determine which sectors of the economy or groups of individuals would receive government support? How would the Fed determine the socially optimal debt-to-GDP ratio? These are ultimately questions that can only be answered through a robust democratic process.

Vincent Reinhart, chief economist at Mellon (who worked at the Fed for 24 years):

Many members of the FOMC would leap at the chance to control fiscal policy. The pandemic shock may be sufficiently adverse to require more stimulus than the FOMC can provide with its traditional instruments. Moreover, the dislocations are incredibly regressive, disproportionately hurting low-income and minority households, but the FOMC has only blunt tools that work at the aggregate level through financial markets. The latter must matter especially to them, because the Powell Fed speaks more to income and wealth inequalities than any before.

They would do with fiscal policy what they cannot do as monetary policy makers. They would do a lot, given their concern about the economy, but they would sunset it all because of their longer-term concern for financial stability. Out of self-interest, however, they would prefer not to burden their own institution so do not expect any further Exchange Stabilization Fund schemes.

The FOMC would probably approve direct stimulus payments that were more graduated than the CARES Act, extend and enhance unemployment benefits, and give direct aid to states and localities. They would have the Treasury subsidize small businesses and industries that are especially pandemic sensitive. There might be a green tint, as Chair Powell drives a Tesla.

Note the missed opportunity. If the FOMC were granted control over part of fiscal policy, it should be focused on infrastructure planning and spending. Politicians are especially inept with infrastructure projects because they have a short-term and local focus. After all, they have to be elected in their district or state. The FOMC, which has an independent and unelected membership and a long-term and national focus would do a much better job at determining infrastructure projects.

Allison Boxer, an economist at Pacific Investment Management Co.:

If the Fed had fiscal authority in addition to conducting monetary policy, we would expect the FOMC to focus on short-term and longer-term policies to support the economy.

We would expect the Fed to provide immediate relief to households and businesses still suffering from the impacts of the Covid-19 crisis. It could provide grants to small businesses, funding for state and local governments, income support for the unemployed combined with return-to-work incentives, and funding for public health initiatives given the close link between the virus and economic trajectories.

A Fed in charge of fiscal policy would also be uniquely positioned to address longer term challenges for the U.S. economy, without the pressures politicians face to deliver immediate results between elections. We would expect the Fed to focus on the low growth, inflation and neutral interest rate environment that has made conducting monetary policy so difficult for the Fed over the past decade. Policy makers could increase growth and productivity by creating tax incentives that encourage business investment, investing in education and infrastructure, and encouraging higher labor force participation through child-care and earned-income tax incentives. These policies can also address economic adjustment needed after the current crisis, such as re-educating workers from displaced industries. Increasing growth and raising inflation back to the Fed’s target can also help put the U.S. back on a sustainable fiscal path in the long run, something Chair Powell has been focused on.

That all sounds like good policy. However, the 435 members of the U.S. House and the 100 U.S. senators don’t seem to agree. The impasse puts the American economic recovery in jeopardy and puts the focus squarely on the Nov. 3 elections to determine what kind of fiscal relief may come in 2021.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

To contact the author of this story:

Brian Chappatta at bchappatta1@bloomberg.net

To contact the editor responsible for this story:

Daniel Niemi at dniemi1@bloomberg.net