‘From each according to ability; to each according to need’ – tracing the biblical roots of socialism’s enduring slogan

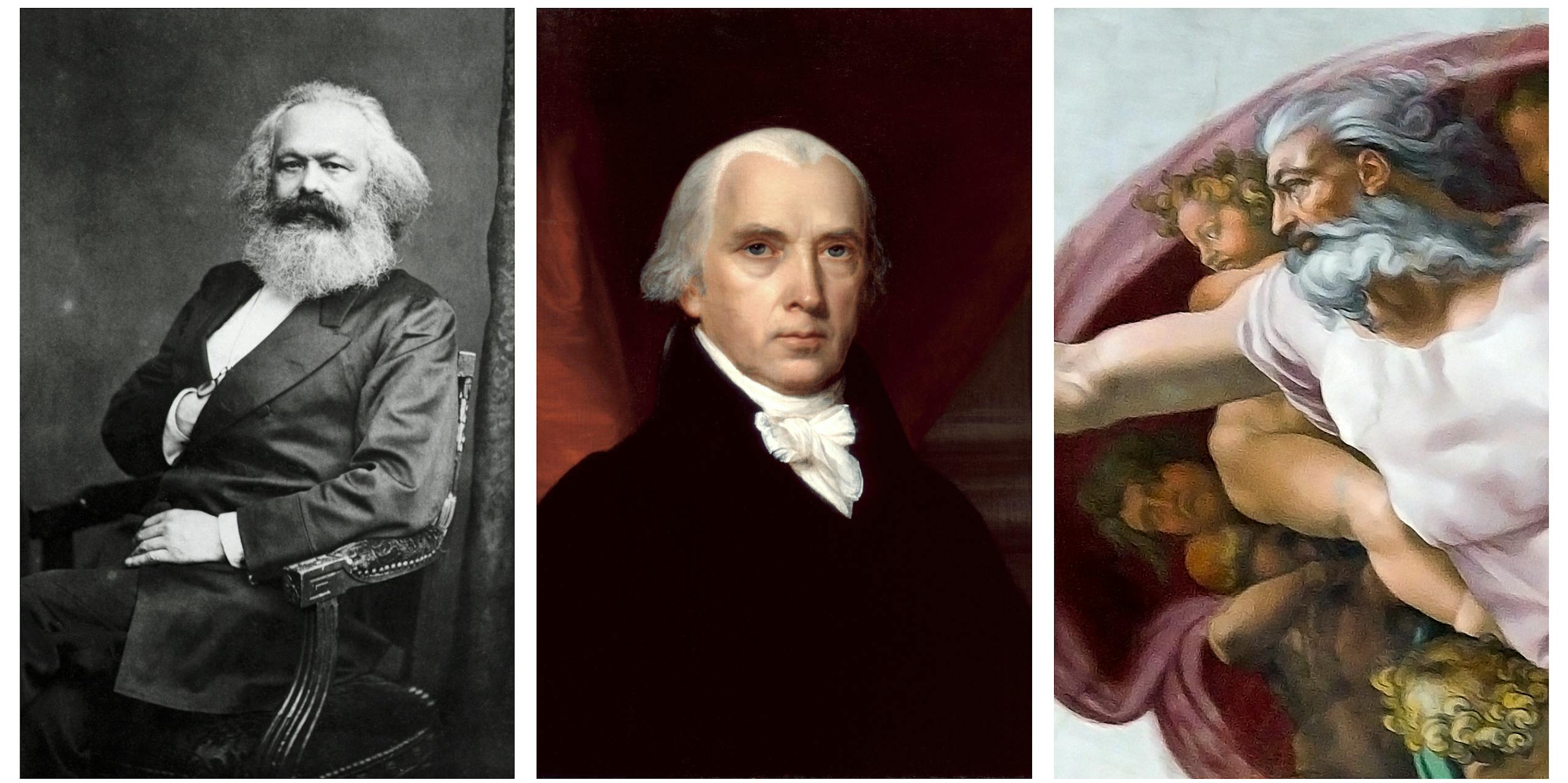

by Luc Bovens“From each according to ability; To each according to need,” is a phrase derived from where?

A) The works of Karl Marx

B) The Bible

C) The Constitution of the United States

If you answered “A,” you are kinda right. But if you answered “B,” you’re not exactly wrong either.

“C,” on the other hand, would get you zero points. But you would not be alone in getting it wrong. In a 1987 survey, nearly half of Americans surveyed believed the phrase “From each according to ability; To each according to need” came from the U.S. Constitution.

The phrase was, in fact, popularized by Marx in his 1875 Critique of the Gotha Program. But its origins are in France.

From Paris to Moscow

It occurs in the 1848 speeches of the socialist politician Louis Blanc and can be traced further back to the cover of the 1845 edition of philosopher Étienne Cabet’s utopian novel “Voyage en Icarie”: “First right: To Live – To each according to his needs – First duty: To Work – From each according to his ability.”

But a decade and a half before Cabet, the followers of the French political theorist Henri de Saint-Simon coined a similar phrase, “To each according to ability; To each according to works” as an epigraph of their journal L’Organisateur in 1829.

There is a constitution that contains a mix of both phrases, but it isn’t the U.S.‘s. Rather it is the Constitution of the USSR. Joseph Stalin paired “From each according to ability” with “To each according to work” in the 1936 Soviet Constitution.

Communal living

So where does the Bible come in? Well, Saint-Simon, Cabet and Blanc – all committed Christians whose social programs were inspired by their faith – borrowed each of these phrases from French Bible translations of the time, and defended them on scriptural grounds. History of economics scholar Adrien Lutz and I traced these phrases back to these French biblical passages.

“To each according to needs” comes from the Book of Acts documenting the practices of early Christian communities in Jerusalem. In the Book of Acts, believers “were together and had all things in common” and sold their possessions and distributed the proceeds within the community “as any had needs.”

In “Voyage en Icarie,” Cabet tells of a fictional community who practice similar communal living arrangements. He later went to the U.S. and founded a number of “Icarian communities” in the second half of the 19th century, that practiced communal ownership of goods and were governed by egalitarian ideals.

“From each according to ability,” is likewise found in the Book of Acts: “So the disciples determined, everyone according to his ability, to send relief to the brothers living in Judea.” Cabet and Blanc both construed this phrase as a call for Christian servitude. They believed society to be a cooperative venture in which people of means should contribute more.

Investing in talent

“To each according to ability” is in the Gospel of Matthew. In the Parable of the Talents, a master gives his servants different amounts of money – or “talents” – and goes away on a journey: “To one he gave five talents, to another two, to another one, to each according to his ability.” Upon his return, he praises the servants who have invested and increased their allotment but condemns the one who buried the money and simply returned it.

For Saint-Simon, the phrase meant putting jobs and resources in the hands of the most qualified and entrepreneurial people and taking them away from nobility. This would lead to greater productivity, benefiting everyone, and in particular, the most disadvantaged socioeconomic groups in society.

Wages of virtue

“To each according to works” occurs at many junctions in the Bible. For example, St. Paul’s Letter to the Romans states: “[God] will render to each according to his works: To those who by patience in well-doing seek for glory and honor and immortality, he will give eternal life.”

The phrase is also found it in First Corinthians: “He who plants and he who waters are one, and each will receive his wages according to his labor.” Whereas St. Paul’s letter makes rewards contingent on one’s achievements as a single individual, in Corinthians it measures the effort that one brings to a collective endeavor.

The same article in the Soviet Constitution that employs this phrase also contains a quote from a Bible passage found in the Second Letter to the Thessalonians: “If anyone is not willing to work, let him not eat.”

The message is the same, but the background of this quote is interesting. St. Paul, the Christian apostle, believed that he and his co-workers did have a right to be maintained by the Church – presumably because their ministry was a sufficient contribution to the common good.

But they were facing an incentive problem: There were idle and disruptive elements in the Christian community who were trying to free-ride on the communal living arrangements. For this reason, even though they were doing ministry, St. Paul urges his followers to do manual labor to set a model and distance themselves from the free riders.

Nothing new

The sentiments behind these slogans are not confined to the ash heaps of history. Rather, many of the policies from the political left today fit under these simple slogans.

“To each according to need” can be applied to the debate over health care. The aim is to take the provision of health care away from market forces and to make it freely accessible to all who need it. “From each according to ability” is what underlies a concern for the common good and a conception of society as a cooperative venture, with mandatory public service as a matching policy proposal.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

“To each according to ability” is at the core of equal opportunity – an ideal that underlies affirmative action legislation and various policies to increase the accessibility of college. “To each according to work” maps onto the ideal of equal pay for equal work and the push for minimal wage policies, mainly benefiting manual labor jobs.

Two millennia in the making, these phrases illustrate what is said in the book of Ecclesiastes: “There is nothing new under the sun.”