The Indian Express

Swami Agnivesh believed that a theocratic state was dangerous

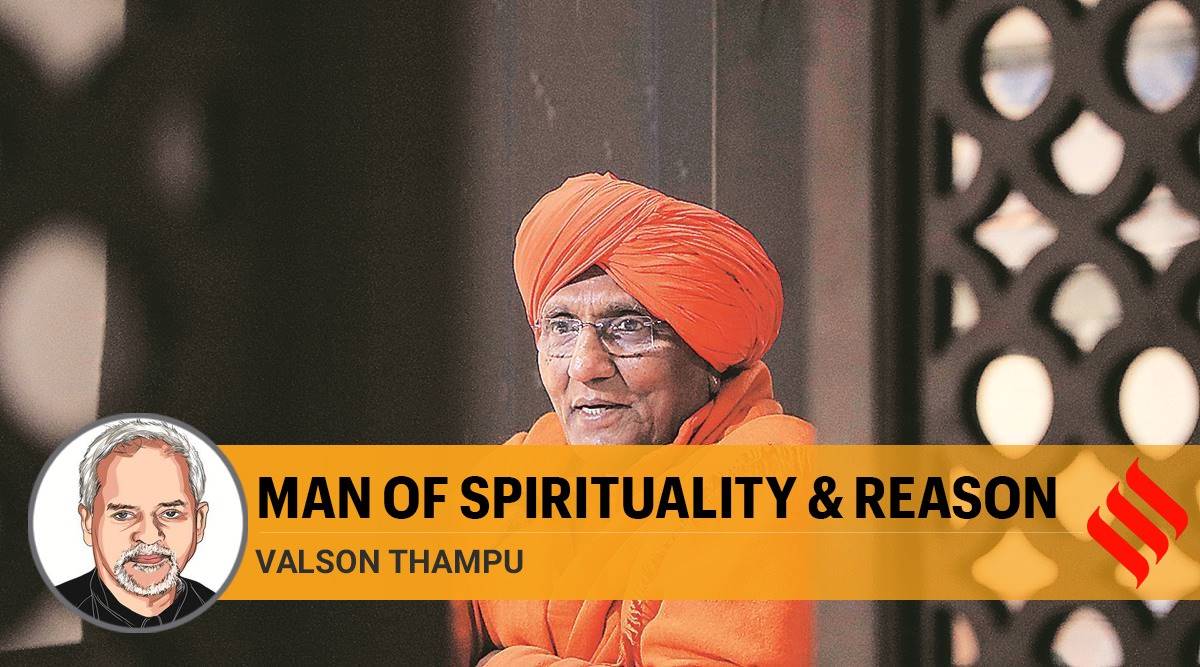

Swami Agnivesh was a votary of secular democracy. He fought to the bitter end the communalisation of the state, which he deemed a crime against history.

by Valson ThampuSwami Agnivesh (1939-2020) spent the last two months of his life in hospital. During this period, we talked to each other almost daily on phone. Never once did he mention the health crisis he was battling. Every word he said was about what needed to be done. He lived and died a quintessential activist.

Our paths crossed a quarter-century ago, accidentally, as it then seemed. Today, it seems willed by destiny. A coincidence, wrote Arthur Koestler, is “two events held together by an unseen hand”. That unseen hand never departed from our association. What struck me first was his rippling vitality, his infectious enthusiasm, his quixotic optimism. He had no patience with the academia, which he had quit at the age of 27. “Your tribe,” he told me, “wastes time interpreting the world. The thing to do is to change it.” That, if you like, was the Marxian streak in him.

His heart was with the poor. I was not surprised, therefore, that he was labelled a communist — a sort of saffron-clad Trojan horse in religion. Swamiji had a knack for turning a slap on the face into a pat on the back. He wore this slur with aplomb. He quoted the South American bishop, Helder Camara, in this connection: “When I give food to the poor they call me a saint; when I ask why they are poor, they call me a Communist.” He was called a Maoist too, a Christian, a Muslim, and the like. There was some truth in all of these, for he loved everyone, including the Maoists. He disapproved their ways, but he regarded them as fellow human beings. That went for Christians, Muslims and Hindus as well.

https://images.indianexpress.com/2020/08/1x1.png

Arguably, the most unorthodox thing about him was his instinct for politics. His detractors held that his religion was a camouflage. But, to him, politics was to spiritual concerns what technology was to science. It secured effectiveness. He should have learned from the life of Gandhi that mixing spirituality and politics — especially standing on spiritual ideals in the practice of politics — is the riskiest thing to do. Like Gandhi, he paid for it, at the fag end of his life.

What is the legacy that this great soul leaves us? From Agnivesh I learned that life is worth nothing if one’s freedom is compromised for any purpose. Maharshi Dayanand being his role-model, Swamiji identified a heroic commitment to truth as the backbone of his spiritual personality. He used to quote Jesus’ words, “The truth will set you free.” The flip-side was that he wouldn’t fit into any system. He was hated even by a section of the Arya Samaj. But millions loved him.

The most crucial thing for him was the idea of God. He believed that misconceiving God was the root cause of religious decay. To him, all religions were equally corrupt in this respect. He concluded that freedom from religion was the sine qua non for practising freedom of religion. To him, love for fellow human beings — especially the downtrodden — was the hallmark of love for God. This made him equate godliness with social spirituality.

He was a votary of secular democracy. He fought to the bitter end the communalisation of the state, which he deemed a crime against history. He was proud of his Vedic vision but believed that a theocratic state was ominous for what it portends. He believed that secularism in India would succeed only on a firm spiritual footing. Spirituality, unlike religion, is guided by reason. Reason is universal, integrative. Faith is divisive.

He was keen to initiate an objective, rational debate on religion. We had been planning to bring out a publication. As he got admitted to the hospital, he reminded me of its urgency. He took an active part in the progress of this work from his hospital bed to a surprising extent. He read each chapter and offered comments. I feel gratified that the first draft of the manuscript could be completed before Swamiji’s health took an irretrievable turn. I left it to him to title the book. “Let’s call it,” he said, “Children of Eternal Spirit, Unite!”. So it stands.

I feel grateful and privileged to have shared a life lived so fully, richly, vitally. Shakespeare’s words ring in mind as I think of this great soul: “Here was a man indeed; when comes such another?”

Thampu was principal of St Stephen’s College, Delhi