What you need to know about the UK-Japan trade deal

by NishatOn 11 September, the UK and Japan announced a new free trade deal: What does this mean for Brexit?

Today, the UK department for international trade announced a deal had been struck “in principle”, between the UK and Japan.

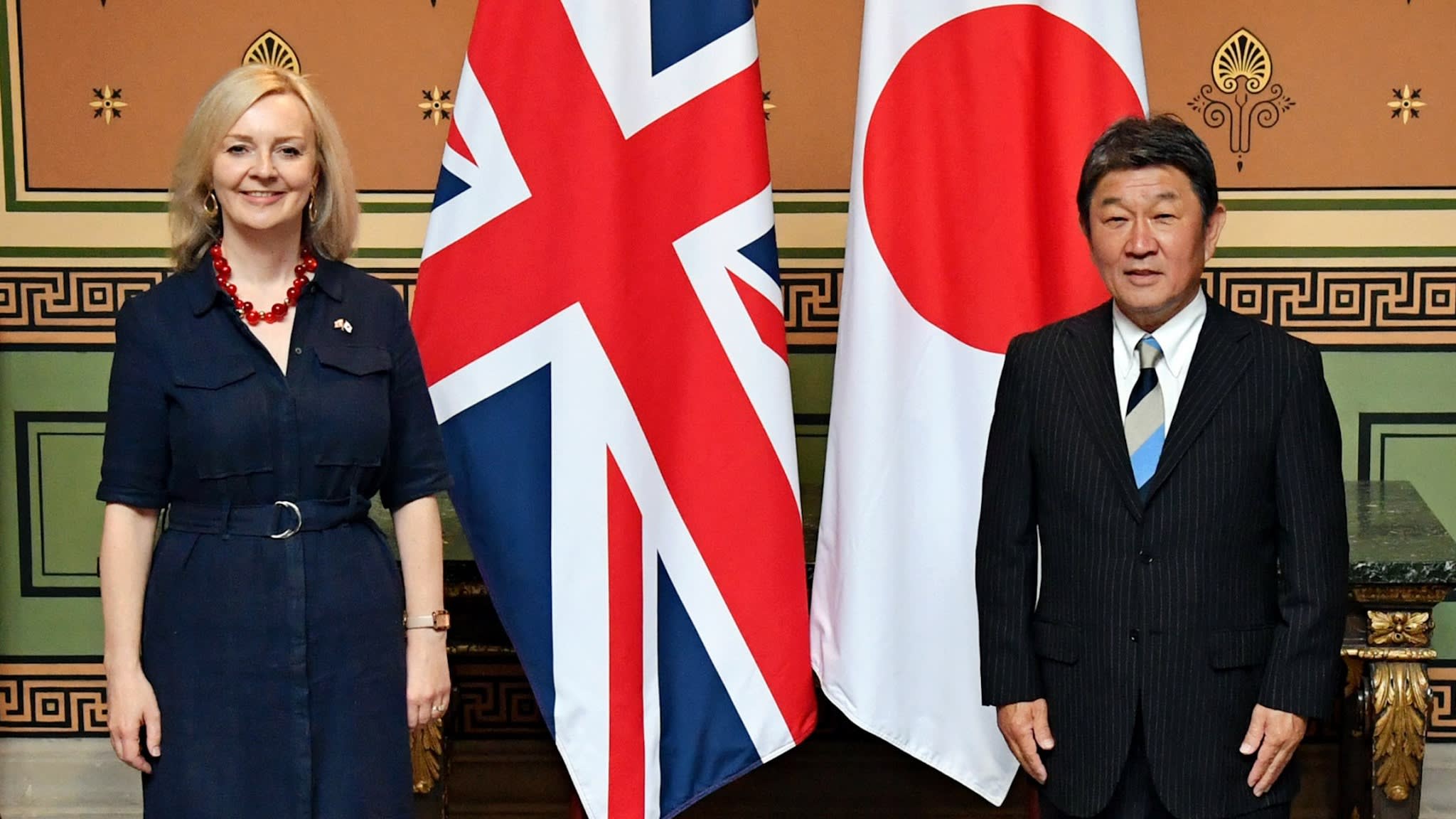

Japanese Foreign Minister Toshimitsu Motegi met with International Trade Secretary Liz Truss on 6 August, for two days of in-person negotiations about the free trade deal which was sealed today. The ‘historic’ deal will come into effect on 1 January, 2021.

International Trade Secretary Liz Truss said:

“This is a historic moment for the UK and Japan as our first major post-Brexit trade deal.

“The agreement we have negotiated – in record time and in challenging circumstances – goes far beyond the existing EU deal, as it secures new wins for British businesses in our great manufacturing, food and drink, and tech industries.”

Shadow international trade secretary Emily Thornberry said:

“Trade with Japan represented 2.21% of our global total last year, and under the best case scenario put forward by the Government, today’s agreement will see that total increase by just 0.07 percentage points each year, simply maintaining the levels of growth seen since 2015, and preserving the forecast benefits of the current EU-Japan agreement.

“That all compares to the 47% of our global trade that we currently have with the EU.”

What will the deal give the UK?

Currently, any trade between the UK and Japan is covered by the European Union-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA). After 2020, the Brexit transition should be complete, which will mean the UK loses any right to trade via EU established EPAs. To replace this key treaty, the UK and Japan have created a hugely similar agreement that will enable continuity of trade.

Key points of the Japan-UK trade deal:

- Secures an estimated £15.2 billion of trade with Japan, over time, accounting for 0.07% of the UK’s GDP (dependant on deal or no-deal)

- However, Department for Trade analysis shows that in 2018, the EU-UK trade was worth £659.5 billion, while trade with Japan was worth £29.1 billion

- UK businesses won’t face tariffs on 99% of exports to Japan

- Businesses will be able to move workers from Japan to the UK, staying for up to 5 years with their dependants

- Lower Japanese tariffs on some agricultural products, including pork, beef and salmon -but not Stilton cheese

- Increased regulatory coordination so that trade limitations on the digital sector will be decreased

- Described by Government as “one step closer” to UK membership of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP)

This deal will translate as a domestic win for Prime Minister Boris Johnson, who is currently facing scrutiny for his suggestion that the UK would break international law to re-draft the Brexit proposal.

What does the deal mean to Japanese companies?

In early 2019, Honda announced that it was closing operations at their lone manufacturing plant in the UK, with a loss of 3500 jobs. Before Honda, Nissan cancelled their plans for building a new car in England. Sony and Panasonic are still moving their European headquarters from the UK to the Netherlands, explicitly outlining Brexit as a reason.

Professor Han Dorussen at the University of Essex discussed the dynamics of the Japan-UK-EU trade triangle. Writing a blog for LSE, he said:

“After Brexit, the UK hopes to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership, which would secure comparable access to the Japanese market. Regardless, the EPA should provide the UK with a strong framework to strike a trade deal with Japan.

“However, these deals may prove to be largely inconsequential; for Japan the real importance of the UK lies in its access to the EU market. Without free and open trade between the UK and the rest of the EU, Japanese companies will not be impressed by any UK-Japan trade deal.”

What is the difference between EU membership and a trade deal?

The EU currently accounts for over 50% of the UK’s trade relationships. This means that individual EPAs should ideally be created and established before the 2021 cut-off point, enabling all possible trade to continue without interruption. In December 2019, the UK Government promised that 80% of all UK trade would be covered by free trade agreements by 2022.

According to the Trade Justice Movement, in 2018, 53% of UK imports were from the EU, and 45% of UK exports went to the EU. The organisation further say that EU-UK trade includes “service industries like public transport, utilities and banking”, while “digital trade in digital products, services and data is growing swiftly.” This nuanced level of trade creates regulatory concerns that need to be ironed out by any replacement EPA, long before 1 January, 2021.

When the trade deals are ready, they will not discuss anything but trade.

While this sounds obvious, the reality is that multinational companies trading across borders (specifically their investment opportunities) will be the driving force of our trade relationships. Workers’ rights, environmental protections, and energy and transport networks are not protected by a free trade deal. For workers, the concern is that UK would not embody a higher or equal standard to EU employment laws, which a trade deal would cannot fix once the impact of EU law disappears into the horizon.

Public ownership of entities like the NHS could then provide an obstacle to private investment opportunities. The NHS remains at the heart of UK-US trade talks, with a widespread public support for the service to remain publicly owned. The devastating situations unfolding during the pandemic (PPE shortages, care home crises, disproportionate deaths of minorities) have created even more electorate-based pressure on the Government to fund and strengthen the NHS. This shroud of protection exists as long as there is fear for the situation of public institutions like the NHS. Will the pressure effectively hold, as the UK approaches hard deadlines for negotiating a significant number of deals?

Contributor Profile

Nishat Choudhury

Digital Editor

Open Access Government

Email: nchoudhury@openaccessgovernment.org

Twitter: Follow on Twitter