Sign of life on Venus discovered with Hawaii telescope

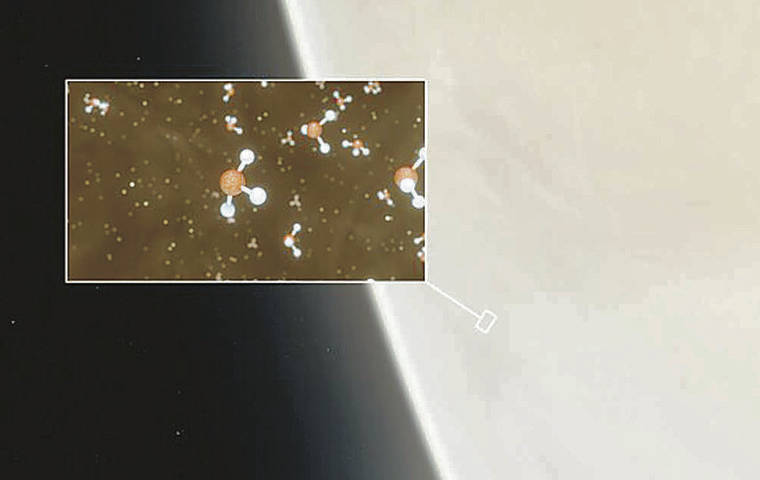

Phosphine molecules were detected in the Venusian high clouds in data from the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope and the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array. The detection of phosphine could point to extraterrestrial “aerial” life. Above, an artistic impression of Venus depicting a representation of phosphine molecules shown in inset.

An international team of scientists using the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope on Hawaii island has discovered the potential for life on Venus.

The discovery of the rare gaseous compound known as phosphine in the clouds of Venus is described in a paper published today in the journal Nature Astronomy. The lead author is Jane Greaves, a former Mauna Kea astronomer who is now a professor at Cardiff University in Wales.

The detection of phosphine in Venus’ atmosphere could well point to extraterrestrial “aerial” life, according to the paper. On Earth this gas of hydrogen and phosphorus is produced naturally only by microbes that exist in oxygen-free environments.

The first detection of phosphine in the clouds of Venus occurred using the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope, the radio telescope where Greaves worked in the 1990s.

The JCMT is the largest single-dish astronomical telescope in the world designed specifically to operate in the submillimeter wavelength region of the electromagnetic spectrum and was one of the observatories used by scientists who last year unveiled the first image of a black hole.

After finding phosphine on Venus in Hawaii, the team of scientists reaffirmed the discovery using the 45 telescopes of the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array in Chile.

In the end both facilities saw the same thing: faint absorption at the right wavelength to be phosphine gas, where the molecules are backlit by the warmer clouds below.

“These results are incredible,” said Jessica Dempsey, the JCMT’s deputy director. “They have implications in the search for life outside our solar system.”

Astronomers have speculated for years that high clouds on Venus might offer a home for microbes floating far enough away from the super-hot surface of the planet to obtain water and sunlight but also needing to tolerate extremely high acidity.

Dempsey thought Greaves was crazy when she asked for the telescope time to search for the phospine, which at the time seemed highly unlikely.

“It was so crazy that you could only do what they wanted to do at two or three telescopes on the entire planet, and the others said no,” she said.

But Greaves was family, Dempsey said, and so the JCMT telescope was pointed at Venus for five days in 2017 to see what they could find.

“Even Jane didn’t expect to find a detection,” Dempsey said.

But she did, finding the phosphine in Venus’ midlatitude layer of clouds from about 31 to 37 miles above the planet’s surface.

The team then worked to calculate whether phosphine could come from natural processes on Venus. Most ways — such as minerals blown upward from the surface, volcanoes or lightning — couldn’t make anywhere near enough of it, the scientists found. But the team also discovered that in order to create the observed quantity of phosphine on Venus, terrestrial organisms would need to work at only about 10% of their maximum productivity.

Any microbes on Venus would likely be very different from the ones found on Earth, where bacteria can absorb phosphate minerals, add hydrogen and ultimately expel phosphine gas, they said.

Team member and Massachusetts Institute of Technology researcher Clara Sousa Silva published a paper in January describing phosphine as a promising biosignature gas in exoplanet atmospheres.

Back in Hawaii the JCMT instrument used to capture this phosphine discovery has since been retired; it was replaced by a new and more powerful instrument known as Namakanui.

The new tool, which was named by University of Hawaii-Hilo Hawaiian- language scholar Larry Kimura, has been deployed in the last few months to take additional measurements of Venus for Greaves’ team and to search for other gases associated with life.

Dempsey said that because Venus is so close, it is possible to send a probe to the planet to collect samples from the clouds and bring them back to Earth. The journey, she said, could be accomplished in only three or four months.

The paper lists as authors the four JCMT staff members who operated the telescope here in 2017, including former UH-Hilo astronomy student E’Lisa Lee.

“An observed biochemical process occurring on anything other than Earth has the greatest and most profound implications for our understanding of life on Earth, and life as a concept,” Lee said in a statement.