My weird, nostalgic quest to hunt down a lost online fruit game

As a kid, I vividly remember playing a 2D chat game full of colourful characters with fruit for heads. So why has it seemingly vanished without a trace?

by Alex LeeOne night in 2014, childhood friends Fred Trubridge and Harry Buckle were sipping pints in the pub, reminiscing about the video games they used to play when they were growing up. It was just your average trot down memory lane, until the conversation turned to one particular 2D chat room game that they distinctly remember playing in the early 2000s. That’s when things turned weird.

Although the name of the game escaped them, both had a clear memory of how it looked. In the game, you played as anthropomorphised fruit, interacting with other players in a garish 2D environment. The game, they remembered, was linked to a children’s food or drink brand – Fruit Winders or Ribena, perhaps – and the characters were painted with flat, bold colours, complete with horribly clashing blues and oranges.

It was similar to other chat room games of its time, such as Habbo Hotel or IMVU, where there was little point to the game other than to give kids a place to hang out in a virtual space. You’d walk around, follow each other to different rooms, and just talk. One of these rooms was decorated to look like a nightclub and was fitted with a bar, despite being a game clearly aimed at kids. Harry remembers how Fred used to pretend to work behind the bar.

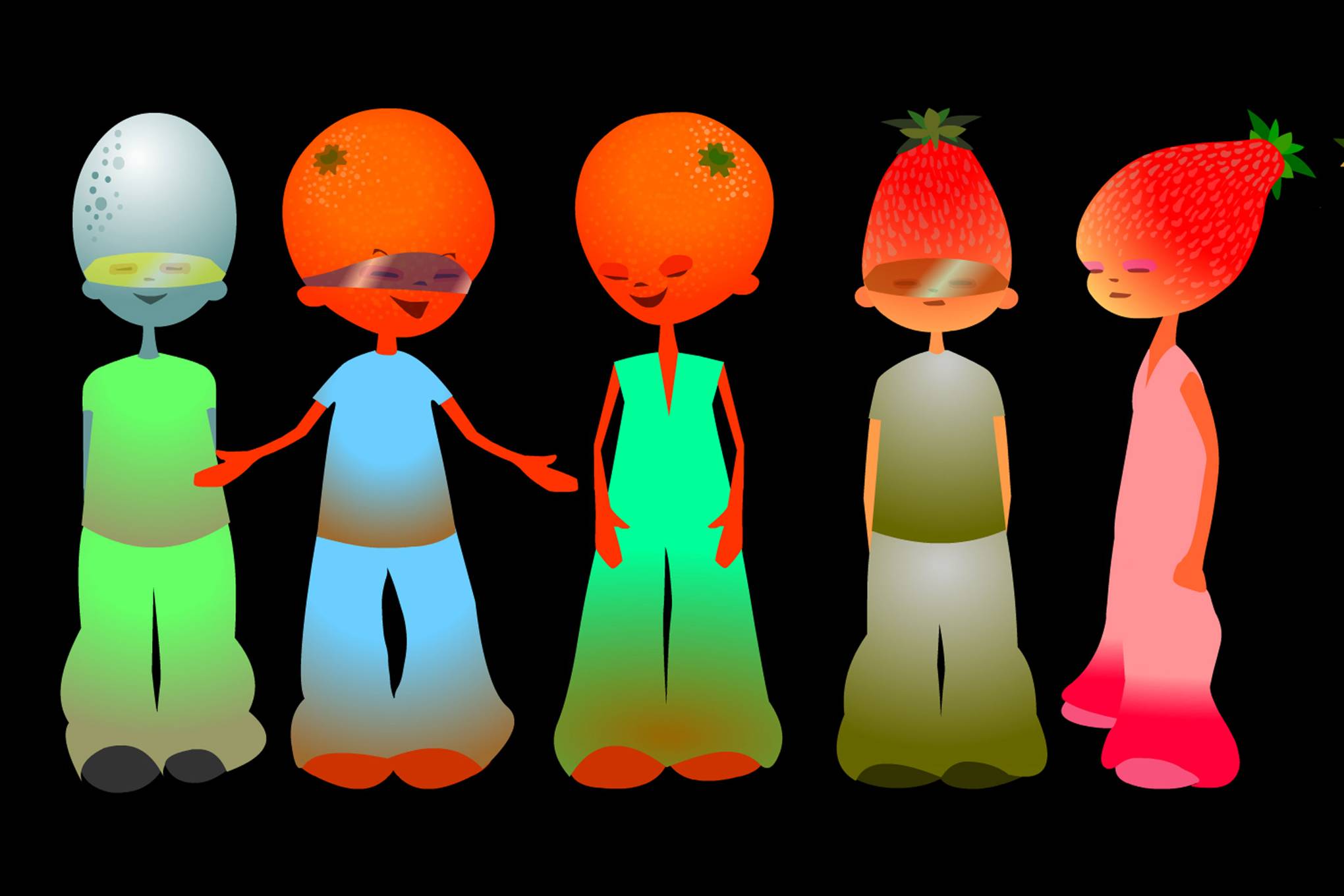

There were a number of characters, but the two that floated to the front of their minds were a male character with a bulbous orange for his head, and a strawberry-headed female character. “I remember the orange-headed avatar because that was the one I used to play as,” explains Harry.

The game has haunted them ever since that fated night in the pub. Not because it was scary, but because it has been seemingly wiped from the face of the internet. “We spent maybe three hours on our phones, just Googling, frantically trying to find this game,” Harry recalls. But despite all those hours feverishly searching, typing in a variety of search terms they knew should bring up the game, nothing ever appeared.

Over the course of seven years, Fred and Harry periodically returned to Google, trying again with new leads and new ideas for search terms they hadn’t tried before. Each time, they drew a blank. There was no mention of the game when they scoured the Wikipedia pages or brand sites like Fruit Winders, Capri Sun, Ribena and Sunny Delight, or when they searched through historical screenshots of brand sites on the Wayback Machine internet archive.

In 2019, Fred turned to Reddit for help. He posted on the subreddit r/TipOfMyJoystick to see if anyone else remembered it. There was only one comment, from a user who suggested that it could be a game called OnChat. But after a quick Google search, Fred knew that wasn't right. OnChat was three-dimensional, for starters, and the game was populated with users’ own avatar creations. This game – he was certain of it – had purely fruit-based 2D avatars. “No matter what you put in, it just seems like it’s all been wiped. There’s nothing,” Fred says, as he scrolls through pages and pages of images of the term ‘strawberry lady avatar’. “There are so many things, but none of them have any kind of reference to a lady with an actual strawberry head, which is a thing I can so vividly remember.”

I knew exactly how Fred and Harry felt, because I had been on almost exactly the same adventure. As a kid, I’d come home from school and hop on my computer to play browser-based games – sometimes Runescape, sometimes Neopets, and sometimes a game whose name I couldn’t remember, situated in a virtual world made of fruit. I’d spend hours dashing around, not really doing anything besides chatting to people and killing time. It wasn’t the coolest game in the world, nor the most exciting, but I remember having fun and wanting desperately to relive the experience.

But as I went searching for it, nothing appeared. While I was easily able to find other games of my youth, this one eluded me. The only reference to this fruity kingdom was Fred's Reddit post – which offered confirmation that I wasn’t alone, but a frustrating lack of details.

Before I knew it, I was spiralling down into the fruity rabbit hole in search of answers to the same questions that have plagued Fred and Harry for years. What happened to this game? Why did it shut down? And why was there no evidence online of it ever existing?

When I speak to Richard Bartle, the creator of the first multi-user dungeon and an expert on virtual worlds, and Betsy Book, who ran and hosted virtual worlds in the early to mid-2000s, neither of them are familiar with the game. It isn’t all that surprising, considering there were hundreds – potentially even thousands – of virtual worlds in the early 2000s. But many of these virtual worlds have some kind of digital footprint, hinting that the game I was looking for either wasn’t very popular, or that it wasn’t adequately archived or preserved.

According to Stanford University’s Preserving Virtual Worlds project, which ran between 2007 and 2010, no fewer than 17 virtual worlds winked out of existence during the length of the project, with varying degrees of fanfare. Some of these games, like The Sims Online, were fairly popular, and tears were shed when the game’s plug was pulled, while other, smaller virtual worlds, just died out with very little care. “It’s not realistic that one type of technology, especially if it’s based on a cultural artefact or one single brand, would live on beyond a few years,” adds Book, who also reviewed virtual worlds on the now defunct website Virtual World Review.

In May 1998, Book had just opened a new virtual world chat room called the Xena Palace, a 2D visual chat room for fans of the 1995 TV show Xena: Warrior Princess. The chat room was built on something called The Palace, a computer program which allowed people to host their own graphical chat room servers on a centralised platform. The Palace exchanged hands several times in the late 90s, going from Intel and SoftBank to Communities.com. But it shuttered in 2001, leaving fans to pick up the pieces by resurrecting it. Book says that if it hadn’t been digitally preserved by fans, The Palace may have potentially been lost to the mist of time, like my missing fruit game.

Virtual world games are already difficult to archive, with the researchers in the Preserving Virtual Worlds project themselves even struggling to find a way to preserve a game like Second Life, which had thousands of players and received widespread media coverage. Matthew Barr, a video game researcher at the University of Glasgow, says that advergames – games developed just to promote a brand or a product – are even less likely to be preserved. The majority of advergames have almost entirely disappeared. “They generally weren’t intended to be available in the long term,” he explains. “by their nature, they're kind of ephemeral and disposable, and they’re unlikely to be good.”

That’s why Barr says he’s surprised this game made such an impact that there are people actively looking for it. Very few advergames have been able to lodge themselves in the public consciousness, with older arcade and console games being the exception to this rule. The 1983 arcade game Tapper, where you served thirsty patrons at a bar, was made by Budweiser, and has since become a classic of the genre, even featuring in the film Wreck-It Ralph. Another example is 7Up’s platformer game Cool Spot, initially made for the Mega Drive and Super Nintendo Entertainment System, was ported to other game consoles like the GameBoy. Both these advergames were well-preserved, being adapted over and over again, and continue to live on in people’s memories.

But it was during the early 2000s when cheap-to-produce browser-based advergames really took hold, with brands notably pairing their product with virtual worlds during the height of their popularity. “I just remember being amazed at how many different brands were interested in virtual worlds,” Book says. But even she is intrigued by this game’s lack of a digital footprint, especially as the fruity realm clearly made an impact, even if it was a tiny one.

“Whoever else we talk about this with would probably think, ‘Oh it’s just a dumb internet game, why the hell would you care?’ and they’re quite right.” says Fred, when I call him to discuss the game. “But it was part of growing up in the internet age. Our history. We’ll never play it again or anything, but we just want to see it again and know we haven’t made it up.” Fred admits that just knowing someone else remembered this game takes a little bit of weight off his shoulders. “There was the potential that we were just going a little bit crazy,” he says.

But I was still confused. If we all had such vivid memories of the game, why did it seem like we were the only ones who remembered it? I had a sense that the game was distinctively British, so I decided to post to Reddit one last time, this time on a subreddit used most commonly by people who lived in the UK.

I left the post to linger, in the meantime contacting brands to try and verify the game’s existence and getting stonewalled at every turn. But then my phone buzzed with a notification. Someone had responded. A user named hinapyon not only remembered the game, but they even remembered its title.

The game existed! It was linked to the kids drink brand Capri Sun, and it was called Planet Juice.

In order to see this embed, you must give consent to Social Media cookies. Open my cookie preferences.

Even equipped with the name, it’s difficult to find out anything about Planet Juice. Google brings up a juice bar in Florida, and the drinks menu for an organic restaurant, while adding Capri Sun to the search only returns a handful of results. One is a 2011 DeviantArt post from someone bemoaning the end of the game, furious about not receiving a reply from Capri Sun when they emailed to ask the company why. There’s a link to a 2001 Campaign article announcing the launch of Planet Juice; a YouTube link with a TV commercial from 2003; and finally, a link to a blog post from 2019 from an advertising agency called Magnetic North based in Manchester. I had found the creators of the game.

Practically all of the people who worked on Planet Juice have moved on from Magnetic North since the game came to an end. Brendan Dawes, who was the creative director of the agency at the time, is astounded to hear the words Planet Juice being uttered when I get in touch with him. “To be honest,” he says, laughing. “I had no idea that all these years on people were still remembering this thing, like a much-loved TV show or something.”

In the year 2000, the Coca-Cola-owned kids juice brand Capri Sun was looking to build a more engaging web presence as brands went online for the first time. The brief was fairly open. It wanted to create something interactive, with very stripped back branding. The finished product didn’t have to be a game, let alone a virtual world, but that’s what the then fresh-faced ad agency Magnetic North went with. “Looking back on it now, in hindsight, it was a real innovative thing for its time,” says Dawes. After six months of development, and sleepless nights in the office trying to perfect it days before launching, Planet Juice finally opened in 2001.

The game was roughly as I remembered. There were five fruit-headed avatars – orange, strawberry, blueberry, pineapple and raspberry (called Juiclings) for players to choose from. And in the lore, they all inhabited their own zone based around the five flavours - wicked zone, crazy zone, chilled zone, party zone and cheeky zone. The striking characters were drawn by Suzie Webb, who was recently out of art school at the time, and inspired by the work of graffiti artist Vaughn Bode.

While users could chat to each other in the game, kids could only select from pre-set text options from a chat panel of safe words and phrases which could be joined up to form a sentence. The game also contained minigames, including bowling and one where the user played the role of a DJ. But Planet Juice was very much like many virtual world games in the early 2000s. Kids were encouraged to just walk around and interact with other fruit-headed kids in a safe environment, throwing splatters of juice at each other and striking dance poses. “We just wanted people to enjoy it, for it to be safe and for parents to trust that they can go on here and know that they can't communicate with anybody in an inappropriate manner,” says Webb.

From what Webb and Dawes remember, it was a “really popular” game. Roughly 200,000 kids logged onto the game during its short life. But as Book suggested, all good things must come to an end. Two to three years later, the game shut its doors for good.

The reason why it ended was less spectacular than one would hope. Dawes says that despite the number of users remaining high right up to the end of the game’s lifecycle, Capri Sun simply wanted to take the brand in a different direction. Like many other advergames, Planet Juice was just one brand’s fleeting vision. “I think we tried to convince them that this could continue to be huge and even bigger, but they didn't really get it back then. To them, it was just a website – who cares?” he says.

Magnetic North went on to make a more traditional Miniclip-style website with stronger Capri Sun branding for the juice company. The advertising agency had an internal discussion about carrying the game on by itself, but with intellectual property factors at play and the company’s own client work coming first, that didn’t pan out. “In the end, it just went offline, which a lot of people were upset about,” Dawes remembers.

As for why there is very little information about the game online? Webb says she takes partial responsibility because while she has screenshots of the game, she’s never posted them online. Another reason for its limited online footprint is that Planet Juice opened and closed before the birth of sites like YouTube, so no one was yet in the habit of recording content from their screens. And when you think about the age demographic of Planet Juice’s players, archiving content in the form of screenshots probably wasn’t a huge priority.

Planet Juice also had very minimal branding, which might be why some people remember that it was linked to a brand, but are unsure which one. Webb speculates that maybe it just wasn’t very good at doing the job of what an advergame should be doing, and that’s why Capri Sun decided to can it. “Some might have thought at some point that Planet Juice was what we were promoting, not Capri Sun,” Webb thinks.

But a major reason why Planet Juice could have fallen off the face of the internet is because the game was made in Adobe Flash, a nearly obsolescent piece of software which will be discontinued at the end of the year. In the early 2000s, thousands and thousands of browser-based games were being built in Adobe Flash, but none of them were being archived and preserved. “Flash was a little bit complicated in that everything was muddled together, and the code was mixed in with the graphics,” says Barr. The way Adobe Flash is coded means that games made on the platform are incredibly difficult to replicate. “It’s not a case of getting the source code and modifying that and pointing it to the new assets. It was kind of a closed system.”

Even if it had been archived, Planet Juice was a virtual world which ran on servers that went offline when Magnetic North closed the game’s doors. If you found an archived version of the website, the only thing you’d be greeted with is the jigsaw puzzle piece of doom. Those two things combined provide the perfect recipe for the loss of a game, and with it, many people’s early internet heritage.

For lots of gamers, it’s the nostalgic experience of playing the game which they want to revisit. The circumstances in which they were playing the game, the cultural setting and the players inside the game itself make up as much a part of the game as the game itself. That begins with not only recording footage of the game being played at the time, but also talking to the gamers playing it themselves. It’s something that Barr is keen on pointing out. “The only way you're really going to be able to preserve a game is to talk to people who played it. Ideally, as close to the time as possible,” he emphasises.

Everything comes flooding back when Webb shares with me the images and screenshots of the game which she finds buried on her hard drive. Seeing them might not truly bring back the pleasure of being a kid, running around inside Planet Juice, but it’s satisfying to know that at least it definitely existed. “Hopefully, when it was on there, people really enjoyed it. It has obviously captured a moment in time for people,” says Dawes when I explain the long quest I’ve been on to find this lost fruit game. “I'm just sorry it disappeared.”

Fred was out shopping when I told him the news. “I just couldn’t believe it. Honestly, it was such a delight to know what it was,” he says. “I think the only thing Harry and I would love to do now is play it.”

With the world now revolving so firmly around the internet, Harry and Fred say that it’s never been more important to keep a record of these games. Planet Juice is living proof of why that’s the case. “It’s sad in a way to hear that its success was sold so short,” Fred says, thinking about the fate of Planet Juice, and the end of his seven-year search. “We didn’t think there was going to be anybody else that actually cared about this thing. The reason for that is because it doesn’t matter really; this is just another silly online game. But for us, the point is, it meant a lot. It was fun, and we loved it.”

Alex Lee is a writer for WIRED. He tweets from @1AlexL

More great stories from WIRED

💾 Inside the secret plan to reboot Isis from a huge digital backup

⌚ Your Apple Watch could soon tell you if you’ve got coronavirus. Here's how

🗺️ Fed up of giving your data away? Try these privacy-friendly Google Maps alternatives instead

🔊 Listen to The WIRED Podcast, the week in science, technology and culture, delivered every Friday