The Indian Express

Challenge to nurture India has become bigger with the outbreak of COVID-19

For “POSHAN Maah” to contribute towards the holistic nourishment of children and a malnutrition free India by 2030, the government needs to address the multi-dimensional determinants of malnutrition on an urgent basis.

by Ashok GulatiPrime Minister Narendra Modi and Home Minister Amit Shah have launched a campaign declaring the month of September as “POSHAN Maah 2020”. By inviting citizens to send nutritional recipes, the campaign aims to create awareness about the POSHAN Abhiyan through community mobilisation. But how far it can help solve India’s massive malnutrition problem remains an open question.

Here we dive deeper into the issue of malnutrition, especially amongst children below the age of five years. We also present some research evidence on its key determinants, and based on that evidence, outline what policy measures could help India overcome this problem of malnutrition by 2030. Incidentally, ending all forms of malnutrition by 2030 is also the target of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG-2) of Zero Hunger.

Globally, there were 673 million undernourished people, of which 189.2 million (28 per cent) were in India in 2017-19, as per the combined report of FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO (FAO, et.al. 2020) on “The state of Food Security and Nutrition in the World”. Additionally, India accounts for 28 per cent (40.3 million) of the world’s stunted children (low height-for-age) under five years of age, and 43 per cent (20.1 million) of the world’s wasted children (low weight-for-height) in 2019.

https://images.indianexpress.com/2020/08/1x1.png

As a proportion of India’s own population, around 14 per cent were undernourished during 2017-19. In China and Brazil, the prevalence of under-nourishment in their respective total population was less than 2.5 per cent.

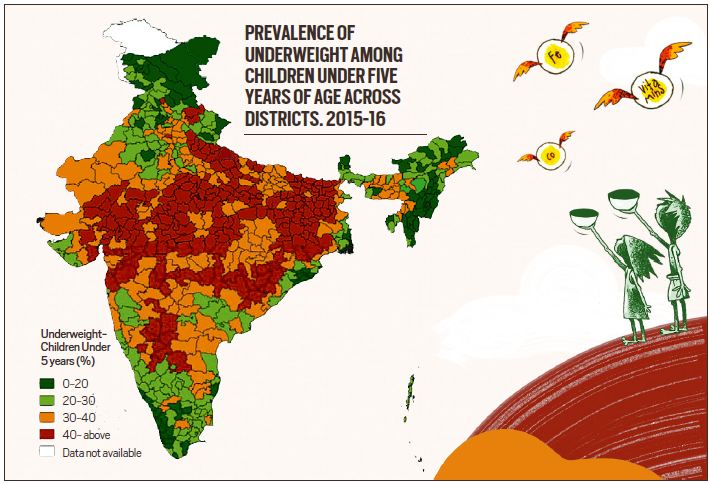

In India, the problem has been more severe amongst children below the age of five years. As per the National Family Health Survey (NFHS, 2015-16), the proportion of underweight and stunted children was as high as 35.8 per cent and 38.4 per cent respectively. In several districts of Bihar, Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and even Gujarat, the proportion of underweight children was more than 40 per cent (see map).

The National Nutrition Mission (NNM), also known as the POSHAN Abhiyan, aims to reduce stunting, underweight and low birth weight each by 2 per cent per annum; and anaemia among children, adolescent girls and women, each by 3 per cent per annum by 2022. However, the Global Burden of Disease Study 1990–2017 has estimated that if the current trend continues, India cannot achieve these targets under NNM by 2022.

We have done deeper research using unit-level data of NFHS (2015-16) (with a sample of 2,19,796 children under five years age) on the determinants of malnutrition. We find that the mothers’ education, particularly higher education, has the strongest inverse association with under-nutrition. Women’s education has a multiplier effect not only on household food security but also on the child’s feeding practice and the sanitation facility. Despite India’s considerable improvement in female literacy, only 13.7 per cent of women have received higher education (NFHS, 2015-16). This is way below several countries at comparable income levels. Therefore, programmes that promote women’s higher education such as liberal scholarships for women need to be accorded a much higher priority. Lack of basic facilities in school infrastructure such as separate toilets for girls, as well as the distance between the school and home, are major factors for higher dropout rates among girls. State governments need to promote schooling via the provision of separate sanitation facilities for girls in schools. Initiatives like the distribution of bicycles to girls in secondary and high schools could help reduce the dropout rates among girls.

The second key determinant of child under-nutrition is the wealth index, which subsumes access to sanitation facilities and safe drinking water. WASH initiatives, that is, safe drinking water, sanitation and hygiene, are critical for improving child nutritional outcomes. In this context, it was commendable that the Prime Minister launched the Swachh Bharat Abhiyan in October 2014 to eliminate open defecation and bring about behavioural changes in hygiene and sanitation practices. In five years of the Abhiyan, as per government records, rural sanitation coverage has gone from 38.7 per cent in 2014 to 100 per cent in 2019, while the sanitation coverage in urban cites has gone up to 99 per cent by September 2020. This remarkable achievement of the Swachh Bharat Abhiyan, subject to third-party evaluations, is expected to have a multiplier effect on nutritional outcomes. However, behavioural change towards personal hygiene still needs to be promoted at the grassroots level.

The third factor is leveraging agricultural policies and programmes to be more “nutrition-sensitive” and reinforcing diet diversification towards a nutrient-rich diet. Food-based safety nets in India are biased in favour of staples (rice and wheat). They need to provide a more diversified food basket, including coarse grains, millets, pulses and bio-fortified staples to improve the nutritional status of pre-school children and women of reproductive age. Bio-fortification is very cost-effective in improving the diet of households and the nutritional status of children. The Harvest Plus programme of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) has implemented it successfully in many countries around the world. The Harvest-Plus programme of CGIAR can work with the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) to grow new varieties of nutrient-rich staple food crops such as iron and zinc bio-fortified pearl millet, zinc-bio fortified rice and wheat; iron bio-fortified beans in India.

Lastly, the promotion of exclusive breastfeeding and the introduction of complementary foods and a diversified diet after the first six months is essential to meet the nutritional needs of infants and ensure appropriate growth and cognitive development of children. Access and utilisation of prenatal and postnatal health care services also play a significant role in curbing undernutrition among children. Aanganwadi workers and community participation can bring significant improvements in child-caring practices and antenatal care for mother and children through comprehensive awareness programmes.

For “POSHAN Maah” to contribute towards the holistic nourishment of children and a malnutrition free India by 2030, the government needs to address the multi-dimensional determinants of malnutrition on an urgent basis. The challenge has become bigger with the outbreak of COVID-19. Can India meet this challenge? Only time will tell.

Gulati is Infosys Chair Professor for Agriculture and Jose is Research Fellow at ICRIER