Psychedelics and Consciousness

Can psychedelic drugs provide genuine insight?

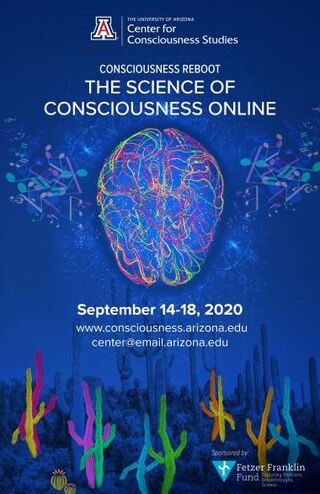

by Susan Blackmore Ph.D.This week comes the first online version of the famous TSC consciousness conference, normally held every other year in Tucson, Arizona. ‘TSC’ originally meant ‘Towards a Science of Consciousness’ but now the conference is proudly called ‘The Science of Consciousness’. I guess it’s true that since the first TSC in 1994 ‘consciousness’ has gone from being a far-fringe topic to one of the most exciting in neuroscience and psychology.

This year there is plenty on psychedelics: a symposium and panel today (Monday September 14th 2020), a plenary on Tuesday on psychedelic science, and another on Wednesday about psychedelic experiences. This really seems to herald the coming-together of neuroscience/psychopharmacology with accounts of what it’s like to be a mind altered by a psychedelic drug.

The Monday symposium begins with talks by such famous researchers and explorers as Andrew Weil, Michael Pollan, and Robin Carhart-Harris, followed by a large panel having just five-minutes each. I’m one of these but since the time difference between the UK and Arizona is 8 hours, this would mean speaking live at 3 a.m. I would not be coherent! Instead, I’ve recorded a five-minute video which you can watch here.

I asked what is, for me, the most fundamental question posed by psychedelics, one that is central to why I take them at all. This is – we sometimes seem to have deep insights when tripping on LSD, drinking ayahuasca or eating schrooms, but are any of these ‘insights’ valid? Do they give us greater understanding, show us deeper ways of relating to our world, or do they just mess up our brains and make us imagine we have understood deep truths?

The most obvious of psychedelic insights have much in common with mystical experiences. The ordinary sense of being a separate self – that self we thought so utterly important and indispensable – is stripped away; our sense of self can change into nothing and everything, as in classic mystical experiences. In this state there is no me distinct from the experiences I am having. Any attempt I make to control things is hopeless because I am those things. The world is utterly wonderful, endlessly fascinating, and seems alive. Is all this so much nonsense?

I think not, though the questions run far and wide. The greatest problem we have in consciousness studies is dualism, the natural way that all of us, from an early age, discriminate between ‘me’ and ‘other’, between ‘me’ and the rest of the universe. But this ‘me’ is illusory. It is not the persisting, powerful entity it seems to be. In this sense, then, the dissolution of the separate individual self may well be insightful.

My question is often made black and white – are psychedelic experiences a marvellous gateway to wonderful insights or just the ramblings of a poisoned brain? I would take away the ‘just’ and say they are both. If the neurochemical effect is to upset the brain’s ability to construct a stable model of self, it may open awareness to something wider. This may not be a good way to get on with ordinary life in a hectic world, but it can be a glimpse of potentials never previously imagined. And these lead many to take up meditation or other practices that slowly, and in more balanced ways, bring us to the same place.

What then of other psychedelic ‘insights’? I do not think we should accept everything that happens in our befuddled brains as keys to the truth, but some are. Now that serious research into the effects of psychedelics has begun, these are questions we may be able to answer.