What took Wall Street banks so long to appoint a female CEO?

by The EditorsCitigroup has made headlines for becoming the first big Wall Street bank to name a woman as chief executive officer. Jane Fraser, Citigroup's president, will take over from CEO Michael Corbat in February. Laudable as the choice may be, one can’t help but wonder: What took so long?

For years, mounting evidence has suggested that companies with women in top jobs perform better. A 2015 study by U.C. Davis found that the 25 California public companies with the largest share of female directors and highly paid executives delivered a median return on assets more than double that of the state’s 400 largest public firms. A 2016 study by the Petersen Institute for International Economics, looking at almost 22,000 firms from 91 countries, also concluded that women in charge means “unusually strong performance.”

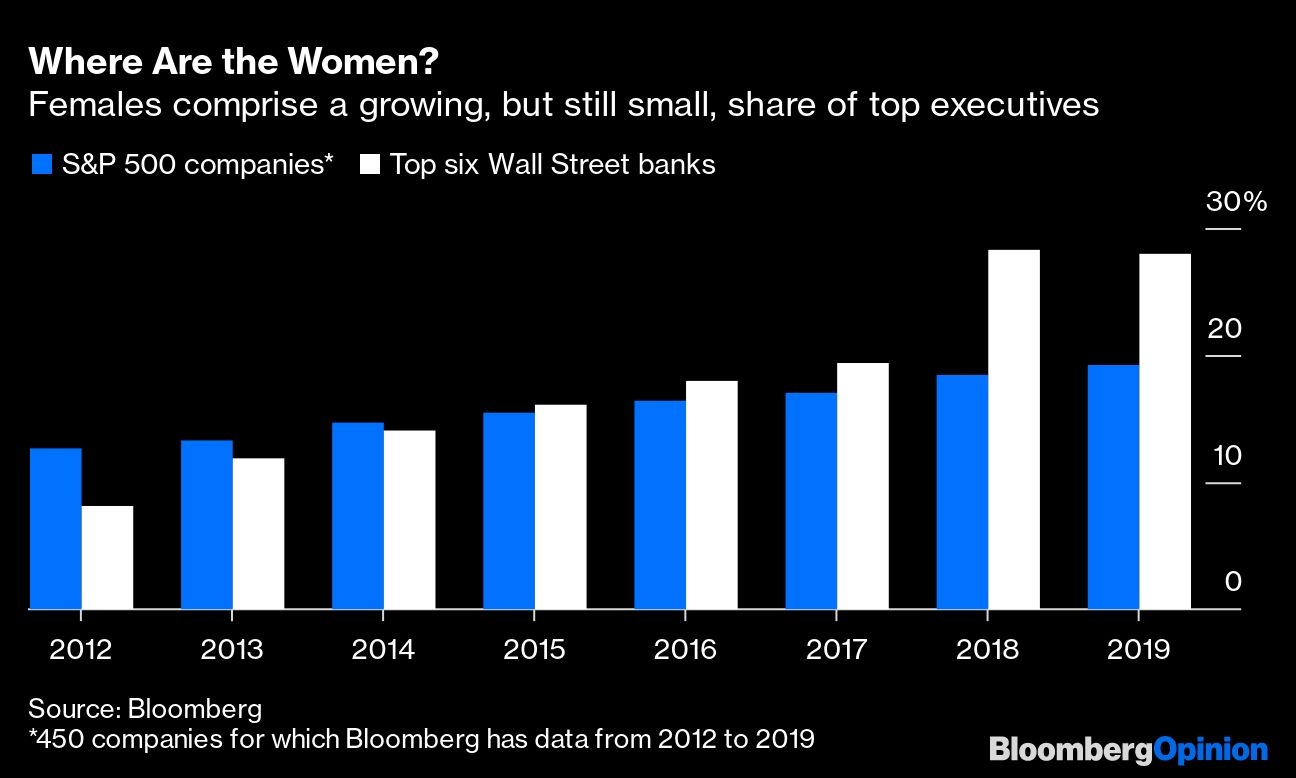

Why don’t supposedly profit-seeking companies already have more women in their C-suites? They’ve been moving in that direction — but too slowly. In 2019, women still accounted for just 19 per cent of top executives and 5 per cent of CEOs at companies in the S&P 500 Index, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.(1) The six biggest Wall Street banks actually had a somewhat better 28 per cent female representation in their executive ranks.

It’s clear that women still face far too many obstacles — from toxic work environments (notably on Wall Street), to family-leave policies and the aggregate effect of numerous smaller barriers. Aside from being morally wrong, these inequities hold back the entire economy, undermining both innovation and productivity.

For the sake of their shareholders, as well as merely doing the right thing, companies should try harder. A recent study by Ernst & Young, for example, found that about half of the largest U.S. publicly traded companies mentioned their commitment to a diverse workforce in their disclosures to investors, but less than a third of those provided any numbers to demonstrate their progress. Standardized measures are readily available. The Sustainability Accounting Standards Board, for example, has developed metrics that enterprises such as Nike already use to track diversity at all levels of seniority. (Bloomberg LP is a founding partner of the SASB, and Bloomberg Philanthropies has provided financial support.) The Securities and Exchange Commission should consider making such disclosures mandatory for public companies, as its investor advisory committee has recommended.

Making the executive team look more like the broader workforce redresses injusFtice and helps the economy. Companies should set that goal and achieve it.

(1) Specifically, companies for which Bloomberg has consistent historical data – 450 in the case of top executives, 449 in the case of CEOs.

Editorials are written by the Bloomberg Opinion editorial board.