Olafur Eliasson

'We've seen it before': Olafur Eliasson on nazism, Brexit – and his new Berlin show

The Icelandic-Dane who brought The Weather Project to the Tate talks art and politics

by Kate ConnollyThe forced confinement of the coronavirus lockdown has inspired Olafur Eliasson’s new Berlin exhibition but it has also given him time to consider the polarisation of politics in Europe and the US.

“To see the British rightwing ‘heiling’ in front of the statue of [Winston] Churchill, the man who beat the Nazis, and Boris Johnson saying it was the Black Lives Matter protesters who were ruining the statue, and deliberately polarising the groups instead of uniting them, was quite something,” he says.

The return of nazism “is something we need to be greatly concerned about,” he believes. “We’ve seen it before, haven’t we?” But he also insists the followers, not the leaders, of the movement should be seen to some extent “as victims as well as perpetrators”.

“I know that’s controversial. But my point is, these hooligans, these rightwingers, these looters, these neo-Nazis, these fucking idiots, they were not born like this, as Nazis.”

The Icelandic-Danish artist, who lives in Berlin, refers to the photograph which went viral of a black protester emerging from the BLM protesters in London, carrying an injured white man in a fireman’s lift. “This white guy is also a victim, which I know will be an unpopular thing to say”.

But Johnson, like Donald Trump, is “deliberately polarising people instead of uniting them,” says Eliasson

He sees what he calls “granularity” in the way the public is becoming inured to what once would have been shocking.

“We’re slowly getting used to calling Mexicans rapists; things are being coloured and twisted and we’re getting used to it and no longer questioning it – it’s like Anne Frank wrote, that after the Nazis burned the books, the next day people got up and went to work. As if they took it for granted, and the problem we have right now is the same insensibility, the numbness,” he says.

Closer to home the lockdown for Eliasson meant, “an opportunity to explore intimacy, break the rules, and re-establish friendships with the ones who live next door and down the street.”

Like many, the homeschooling of his two teenage children caused him a degree of vexation, not least regarding the challenges of digital communication.

“It was horrible. I actually considered making a 3D phone, thinking how do we trust each other if we can’t see the way someone moves, the anger, the happiness? How can we ever get anything done in future if it’s not PowerPointified, Zoomified, McKinseyfied bullshit? How do we prevent it from numbifying our last bit of intimacy? I mean how should we fall in love on a Zoom call?”

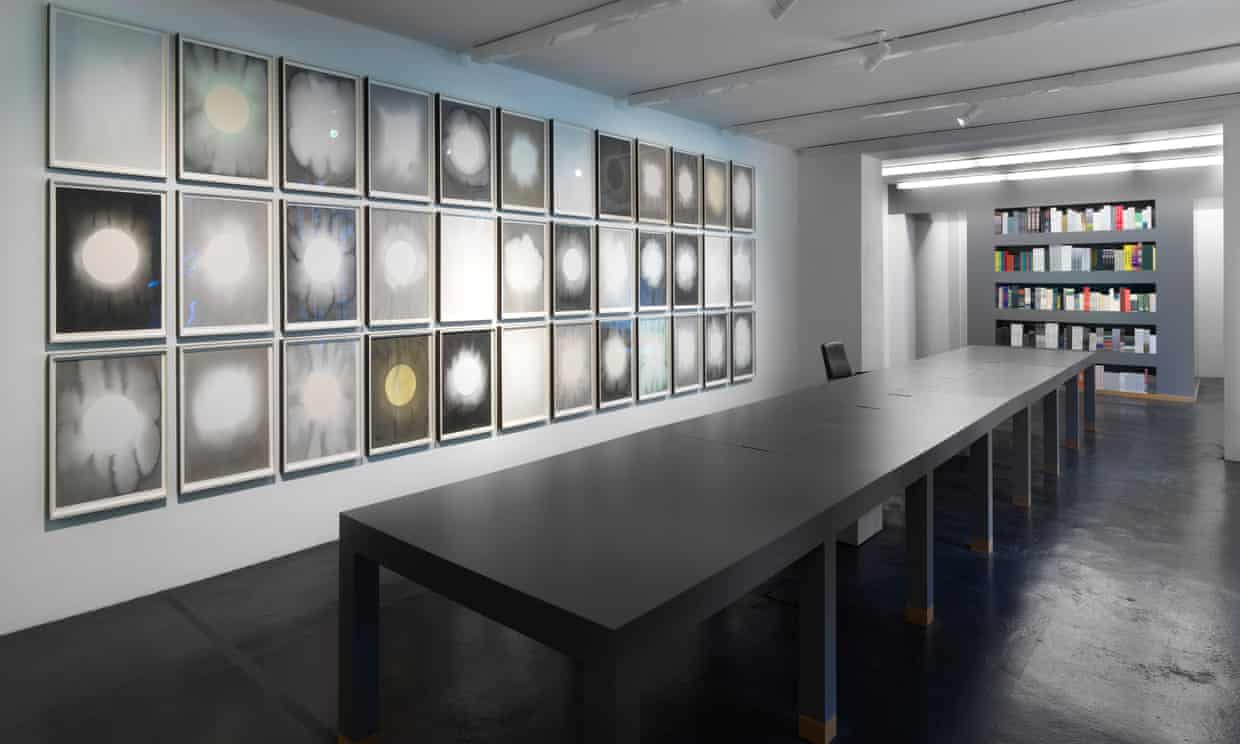

He has explored some of the questions raised by the forced confinement in his latest works, his eighth solo exhibition with the neugerriemschneider in Berlin, a former margarine factory turned leading but discreet art gallery, which first championed him almost three decades ago when he was little-known.

The exhibition, Near future living light, picks up on Eliasson’s longtime exploration of perception, illusion and optical phenomena, with a range of hand-blown glass sculptures, a series of black-and-white water colours and three light installations at the heart of which is a dessert spoon, some cheap lenses, and a crumpled piece of foil.

“During this pandemic, people have been referring to intimacy and distancing a lot and referring to their neighbourhood as something they’re much closer to than they’re used to being,” he says, moving through the darkened gallery, in and out of the shifting shapes and colours of the light projections.

“And we’ve not just had the coronavirus, but also the whole civil rights movement – all the unpacked memories – and a reactivation of humanistic values. And we’re also entering an era of reconsidering the superiority of humans for the wellbeing of the planet. The world is changing at an unbelievable rate,” he says.

Eliasson, who has been held in high regard in the UK ever since his 2003 The Weather Project at Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall, which was viewed by 2 million visitors, has been following the career of Johnson quite closely, he says “like a layman”. And while he does not think he is “as bad as the others”, such as Trump, Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro, Hungary’s Viktor Orbán and Russia’s Vladimir Putin, he is nevertheless fascinated by the similarities between them.

He will be following British politics closer still from now on because his new partner is the London-based Sudanese-British philanthropist, Hadeel Ibrahim. “I will be spending a lot of time in London. I am very connected to the Brits. I think Brexit is a disaster and for some reason the Brits allowed themselves to run into a conflict of illusions ... convinced that yesterday, the Great Britain that once was, will be able to be brought back. Of course I could not feel more sorry because it’s evidently not how it’s going to be.

“When we take a closer look at why people reacted like this, if you ask me, it’s because they felt that no one was listening to them, no one could see them and nobody met and heard them.”

The night before, he addressed a gathering of Europe’s foreign ministers in Berlin – minus the UK’s – to mark the occasion of the German presidency of the European council. He was invited to do so by his friend, the German foreign minister, Heiko Maas. It might have felt tokenistic, reaching out to a popular cultural figurehead except, as Eliasson let the gathering know, “the culture sector in Europe is much bigger than the car industry, with a much bigger turnover,” so it is one they cannot afford to ignore, he insists. He urged the foreign ministers to go home and stress the positive aspects of the EU. “I said to them please can you stop talking about Europe as if it’s a failed project? It’s not. We have the best healthcare system, the best economic stability, the lowest unemployment in the world, the best education, the best human rights and social welfare.”

His new light projections, which he describes as “like a very small theatre, a little like a German expressionistic film, something beautiful and positive” capturing the wonders of early cinematography, are, he stresses, his attempt to “tell a beautiful story for once. Just like I told the foreign ministers, tell me something beautiful, otherwise I can’t go forward. We need to believe in a utopia; we need to be given our dreams back. We must not be deprived of our ability to dream.”

- Olafur Eliasson’s Near future living light runs at the neugerriemschneider gallery until 24 October.