Can You Manage What You Can’t See?

by Nate BennettManagers continue to be tested by the ways the pandemic has disrupted operations. One of their most daunting tasks over the past six months has been maintaining a balance between protecting employees while ensuring their work gets done. When it comes to keeping employees safe, this means more than providing PPE and adopting workplace modifications to discourage the virus's spread. It also involves addressing the anxieties that are inevitable during such times. Towards that end, Wharton professor and workplace expert Adam Grant recommends leaders focus on 'macro-management;' that is, efforts to reinforce to employees the importance and meaning of their work. After all, employees are contending with enough stressors; the last thing they need is oppressive oversight.

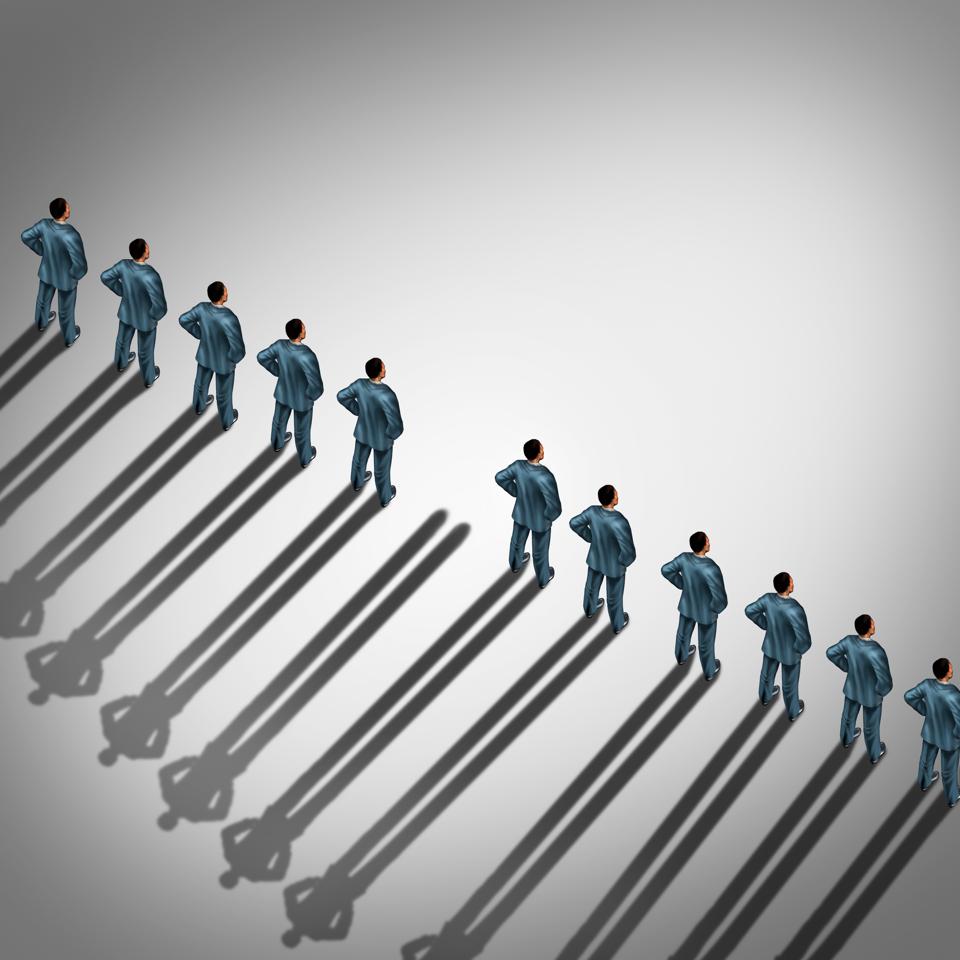

At the same time, work still needs to be done. Managers who find themselves responsible for the performance of suddenly geographically dispersed employees are in a tough spot. When employees toil out of sight, and when employers haven't adopted strategies to assess less visible performance, it is difficult for managers to know how to identify and then help any struggling employees.

It is true that for some time, jobs in the US have increasingly emphasized knowledge work over physical work. By its nature, the level of effort provided by knowledge workers is more difficult to assess. Roland Kidwell, a professor at Florida Atlantic University's College of Business, is an expert on employee effort. He shared, "the provision of effort and its connection to effective performance is not as easy to grasp with knowledge workers because their effort is not visible and their performance can be more a function of what they know than what they do."

Kidwell notes that managing such performance requires a manager to answer two questions. First, has a shared understanding of what a 'fair day's work' – regardless of where it takes place - been accepted by all? Second, are employees reliably available to discuss work issues from their location, and do they demonstrate full participation as part of a work team? And he points out that "companies that built systems to capture answers to these questions before the pandemic are in a much better position to manage the performance of a dispersed workgroup than companies forced into this situation over the last few months." Very few leadership teams had the foresight to anticipate the need to address these questions in advance of the pandemic.

Recognizing that an employee's performance is suffering is just the beginning. Shifts to where and how employees work make it difficult for a manager to intervene to restore performance. Even in the most routine of times, few supervisors relish conversations with poor performing subordinates, and even fewer report they execute them with confidence.

The topic is uncomfortable because the supervisor and employee are by design in a conflict. Predictably, the supervisor tries to create a sense of accountability for performance in the employee. The employee works to deflect these efforts with either an insistence that the supervisor doesn't understand their contributions or reciting a litany of excuses to shift blame in other directions. It is hard work to help an employee develop a sense of ownership for their weaknesses or failures and earn their commitment to a plan to remedy them.

Generally speaking, when an employee's performance is suffering, supervisors are left to ascertain which of four possible explanations is most plausible. An employee may be failing to meet expectations because:

They are not interested in providing the effort necessary for success

They are overmatched by the demands of the job and, even with great effort, are unable to meet expectations

The task they are asked to accomplish is unreasonably difficult, given the resources available

A string of terrible luck has befallen them

Supervisors need to be expert when choosing from these four explanations because the steps necessary to address one will not work for the other. Lack of effort is a motivation problem. An employee unable to do the job requires training, transfer, or termination. When the task is unreasonable, more resources (FTEs, money, equipment, time, information) are required. Finally, when luck is bad, some consolation and cheerleading may be all that is needed to get the employee back in the game. You can't motivate someone out of an ability deficit.

Managers who now find themselves responsible for remote employees' performance will struggle to get an accurate read on performance, to realize when it is suffering, and to develop documentation that supports their conclusions. This is even more so the case when the performance norms and management systems were not designed with remote work in mind. In such companies, suddenly less of what employees do is directly observable. Consequently, the quality of data available to a supervisor to support their understanding of poor performance will suffer. When an employee is remote, and systems that help supervisors understand performance are not in place, it isn't easy to know how to help. It's hard to manage what you can't see.