Zhang Jun shows how China's ongoing technological transformation is cushioning the blow of the pandemic

by Zhang JunDespite taking a serious hit from COVID-19 lockdowns, China’s economy has proved resilient. It has not, however, fully bounced back: some activities, especially in the service sector, simply cannot be revived. Yet, unlike most of the world, China seems unlikely to become mired in a long recession, not least because of its rapid digital transformation.

China’s digital economy was growing strongly before the pandemic. In 2018, it already accounted for CN¥31.3 trillion ($4.7 trillion), or 34.8% of GDP. While this is only about one-third the size of America’s digital economy, it represents years of growth that outpaced that of nominal GDP. The COVID-19 crisis is set to reinforce this trend.

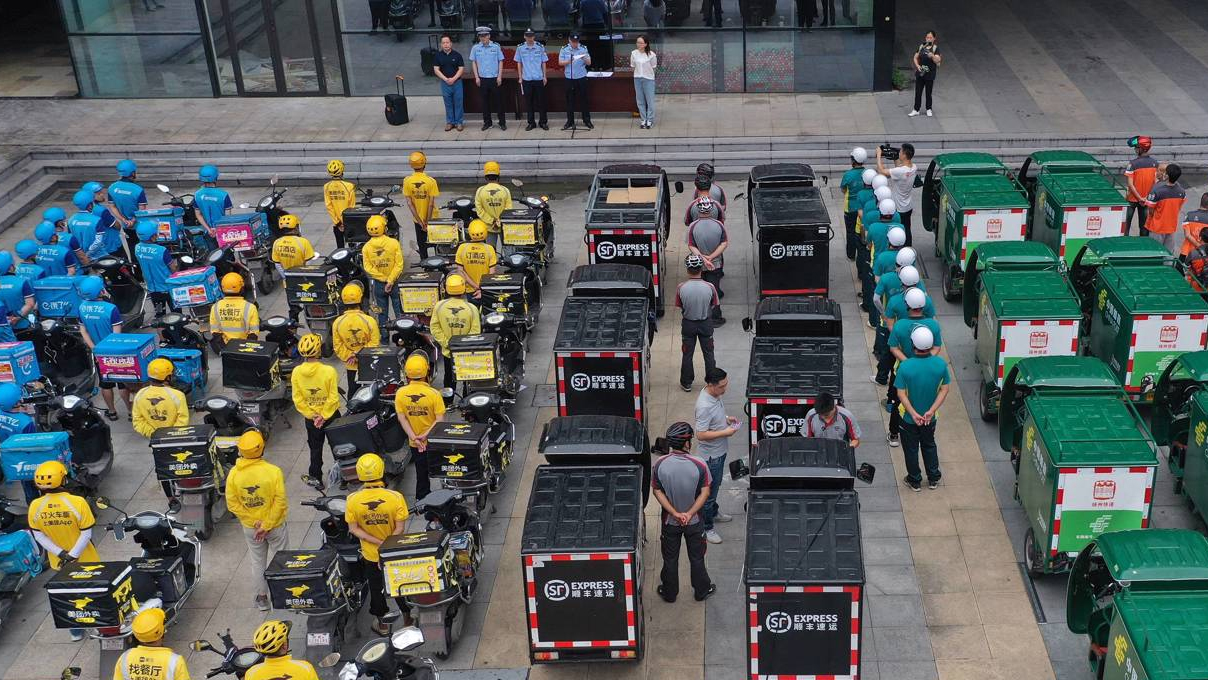

As the pandemic has destroyed some businesses and industries, it has also greatly accelerated the uptake of digital technologies. Unable to leave their homes, households embraced applications like JD.com, Meituan, Eleme, and Pinduoduo, which enabled them to purchase food, oil, vegetables, and daily necessities online.

Moreover, within a month of closing their classrooms and evacuating their campuses, schools and universities moved online – a shift that spurred the rapid development of online conferencing and learning platforms. Likewise, companies took advantage of digital tools – from communication platforms like Enterprise WeChat and DingTalk to e-contracts – to keep their businesses running. More than 20 million online meetings, with more than 100 million total participants, have been initiated on DingTalk in a single day.

Just as technology helped life go on during lockdowns, it has enabled China to roll back restrictions without risking public health. A growing number of local governments are implementing Alipay Health Code – a mobile-phone application that assigns users a color code indicating their health status. That way, they know when they should be quarantined, when they can safely visit public spaces, and when they can travel.

This also lets authorities track – and mitigate – risks. If a person visits, say, an airport or hotel, they must show their personal QR code. A quick scan will show whether they have visited a high-risk area within the last 14 days. Such tracing – not only during travel, but also in schools, offices, and other contexts – is essential to avoid another COVID-19 outbreak and further economically damaging lockdowns.

But the health applications of new digital technologies extend much further, and are transforming China’s entire health-care industry. Beyond the rise of online medication purchases, 5G-based remote medical-consultation platforms, such as Ping An Good Doctor, have been flourishing, laying the groundwork for a new industrial model.

During the initial outbreak in Wuhan, when local hospitals were overwhelmed with COVID-19 patients, such platforms enabled people to consult with medical experts from Beijing via video. As China’s 5G network coverage improves, such remote consultations – including diagnoses, hospital referrals and appointments, and health-management services – will become even more widely accessible. This will be particularly valuable for households that currently lack easy access to better medical resources, say, because they live in remote areas.

Technology is also propelling research and development in health. For example, Huawei’s medical-intelligence app EIhealth is being used for viral genome research, anti-viral drug development, and medical imaging and analysis. It has accelerated the search for COVID-19 treatments and vaccines, and improved virus detection. And, thanks partly to algorithm-assisted screening, frontline hospitals in China have already conducted more CT scans in 2020 than in all of last year.

A similar digital transformation is sweeping China’s financial industry. With 562 million users, China’s mobile-banking apps were the third-largest category of apps by customer base – after short-video and shopping apps – at the end of March. Chinese mobile-banking apps now average 50 million monthly active users.

Beyond making banking more convenient, digital technologies have enabled financial institutions to expand and improve their services. For example, using big data, cloud computing, artificial intelligence, and distributed-computing architecture, commercial banks have vastly improved their ability to serve small and micro businesses and ordinary households.

Financial technology firms have made similar strides. Credit-based financing for small and micro enterprises has long posed a challenge to institutions. Yet, with the help of Alipay and online-banking services, Ant Financial served more than 16 million clients and extended CN¥2 trillion in credit last year. And it is not alone.

The growth of China’s digital economy has been a boon for employment as well. The China Information and Communications Technology Academy reports that in 2018, the digital economy created 191 million jobs and accounted for one-quarter of overall employment – an 11.5% increase year on year.

Among the main beneficiaries of these new jobs are young, educated Chinese, who now have more opportunities to work as independent professionals in a new kind of gig economy. The increased labor-market flexibility brought about by digitalization is likely why urban unemployment hasn’t increased significantly in recent years, despite the decline in GDP growth.

Though China still lags in some key technologies, there is no denying the tremendous progress in its digital transformation. This process is set to continue and even accelerate in the coming years, not least because of the government’s planned investments in new infrastructure, including 5G networks and data centers.

China may well be the only major economy to achieve positive growth this year. It owes this, in no small measure, to a decade of commitment to heavy investment in technology-driven structural transformation.

Zhang Jun is Dean of the School of Economics at Fudan University and Director of the China Center for Economic Studies, a Shanghai-based think-tank. Copyright 2019 Project Syndicate, here with permission.