NFL's Black national anthem is a slap to MLK Jr.

by Tim ConstantineANALYSIS/OPINION:

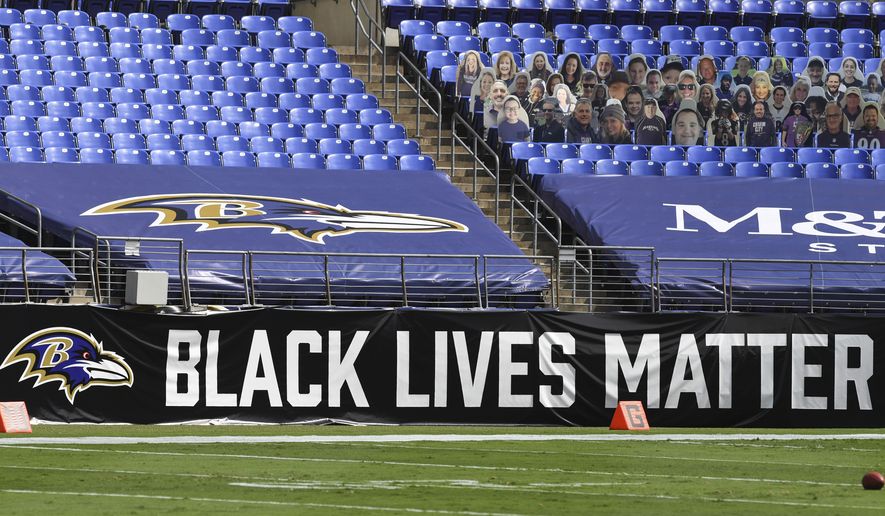

Professional sports are finally in full swing in this, the year of the pandemic. The NBA is playing in its Disney bubble. Major League Baseball’s abbreviated season is hurtling toward an expanded fall playoff picture, and the NFL season has now officially kicked off. Many athletes have proclaimed themselves the social conscience of the country. Professional basketball hardwood floors are imprinted with Black Lives Matter. Multiple sport uniforms feature phrases indicative of social causes. Politics is discussed daily on the television sports networks. This has all become commonplace.

The NFL, however, is taking it to a whole different level.

The NFL’s opening game for the 2020 season was Thursday night between the Kansas City Chiefs and the Houston Texans. The Texans hid in the locker room during the playing of America’s national anthem. In fairness, they hid during both anthems. Both? Yes, the NFL played what is being referred to as the “Black National Anthem” shortly before playing the national anthem of the United States of America.

Merriam-Webster defines a national anthem to be “a song that praises a particular country and that is officially accepted as that country’s song.” “The Star-Spangled Banner” is the only song to ever hold that title in the history of the United States. It was officially recognized as such in a congressional resolution in 1931.

Before the world was 24/7 our national anthem began and ended every broadcast day for television and radio stations all across America. It was played at parades, civic events and in celebration and recognition of our troops. Watching our flag fly and hearing our anthem when American men and women won an Olympic event was a particular moment of pride. Like the Pledge of Allegiance, which recognizes “One nation under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all,” the anthem is a reminder of our good fortune to live in a country where everyone is offered opportunity.

What then is the Black national anthem? What nation does it celebrate? What government officially recognizes it? The intentions of the NFL and Black activists may have been honorable, but the sad reality is that the Black national anthem sets people of color, indeed it sets all of us, back to the 19th century.

One of the most famous Supreme Court cases in United States history is Plessy v. Ferguson. It was the result of an 1892 incident in which a Black man named Homer Plessy refused to sit in a rail car set aside specifically for Black passengers. The Supreme Court essentially upheld racial segregation, under what became known as the “separate but equal doctrine.”

It wasn’t until many years later, in 1954, when hearing Brown v. Board of Education, the Supreme Court found that “the doctrine of separate but equal has no place” in public schools nor anywhere at all. It was at that moment that the civil rights movement truly began.

Less than a decade later, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. spoke his immortal words, dreaming of a day when a man was judged not by the color of his skin, but by the content of his character. Why then do civil rights activists in 2020 have the apparent goal of returning to the late 1800s and the days of “separate but equal?”

Having a separate anthem based on the color of a person’s skin is not one nation. It does not unify. It is divisive. It is racially motivated and completely ignores the lessons MLK taught us and ultimately gave his life for.

Likewise, college student unions divvied up according to race return us to the days of “separate but equal.” Public universities such as the University of Maryland have Black student unions where students of color can gather away and “safe” from the intrusions of white kids. The president of the University of Massachusetts-Amherst Black student union, Rebecca Louisthelmy was quoted in Teen Vogue magazine as saying, “I was drawn to black student union because I wanted to feel a sense of community and belonging from people who look like me.” That is quite literally the opposite of Martin Luther King’s dream.

One nation is made up of only one race. The human race. In the America I dream of, every color and both genders recognize we are all united as one. If our goal is truly one nation that is indivisible, our first step should be to stop dividing it. Separate anthems for non-existent countries based instead on skin color and student unions set up to encourage only those with similar pigment to socialize with each other return us to the very days we claim to want to leave behind.

Separate but equal isn’t one nation.