The Indian Express

Trump pressed for a plasma treatment. Officials worry, is a vaccine next?

White House officials say the president is now doing exactly what his opponents have assailed him for not doing: exerting pressure to develop safe and effective drugs and vaccines as quickly as possible because people are sick and dying, not because of the timing of the election.

by New York TimesWritten by Sharon LaFraniere, Noah Weiland and Michael D. Shear

It was the third week of August, the Republican National Convention was days away, and President Donald Trump was impatient.

White House officials were anxious to showcase a step forward in the battle against the coronavirus: an expansion of the use of blood plasma from recovered patients to treat new ones. For nearly two weeks, however, the National Institutes of Health had held up emergency authorization for the treatment, citing lingering concerns over its effectiveness.

https://images.indianexpress.com/2020/08/1x1.png

So on Wednesday, Aug. 19, Trump called Dr. Francis Collins, the director of the NIH, with a blunt message.

“Get it done by Friday,” he demanded.

It wasn’t done by Friday, and on Sunday, regulators at the Food and Drug Administration still had not finished a last-minute data review intended to ease NIH doubts.

But on Sunday night, the eve of the convention, the president announced, with the FDA’s approval, that plasma therapy would be available for wider use, and he declared that it could reduce deaths by 35%, vastly overstating what the data had shown about the benefits.

Trump’s call to Collins was a flash point in a pressure campaign by the White House to bend the nation’s public health agencies to his desire to show progress in the fight against a pandemic that has killed more than 192,000 people in the United States. And it was just one in a series of moments that have left scientists and regulators across the public health bureaucracy increasingly worried that the White House could exert greater pressure to approve a vaccine before Election Day, even in the absence of agreement on its effectiveness and safety.

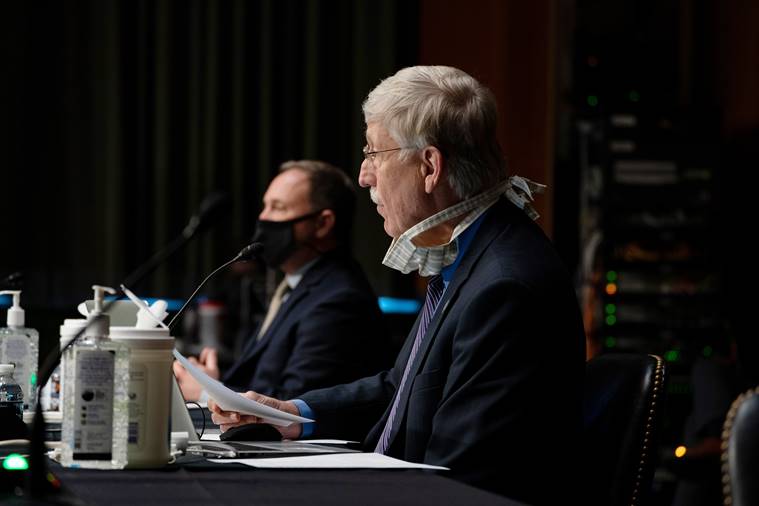

On the night of the plasma announcement, Collins was told to show up at the White House, where he was given a coronavirus test and then shunted to the Roosevelt Room as Trump and others spoke to journalists in the briefing room.

There, Collins and Dr. Peter Marks, one of the top regulators at the FDA and the person most directly responsible for maintaining the independence and scientific rigor of the vaccine approval process, watched helplessly as the president and other top administration officials oversold plasma’s effectiveness, creating a public relations debacle that reverberated for days.

Collins left the White House after the announcement. But Marks, who had pushed for the plasma approval, was escorted to the Oval Office to spend a few minutes with Trump and his top aides, who were celebrating with cupcakes with white icing. In an interview on Friday, Marks said he was “a little bit in a state of shock” to find himself there being thanked by the president for his work on the plasma approval.

Although he described it as “a brief interaction that really didn’t have any substance,” health officials who had heard about the encounter said they feared it could create the impression that the guardrails between politics and science were being further eroded at a time when the public is already concerned about political pressure in assessing the safety of vaccines and treatments.

Some of those present were taken aback when Trump, who a day earlier had tweeted about a “deep state” at the FDA blocking quick approvals of treatments and vaccines to hurt him politically, jokingly asked whether Dr. Stephen Hahn, the FDA commissioner, was doing a good job.

With Election Day just over seven weeks away, Washington is witnessing the collision of two worlds: a community of largely anonymous government scientists and doctors who operate in a culture guided by research, data sets and peer review, and a president famously disdainful of science, politically wounded by his failures to contain the coronavirus and now determined to cast himself as moving as fast as possible to provide Americans with vaccines and treatments.

Government scientists and pharmaceutical companies have begun taking extraordinary steps to counter any impression that they could sacrifice public safety to political expediency, pledging publicly that they are committed to impartial scientific decisions about fighting the coronavirus.

Hahn has publicly committed to vetting any vaccine approval through an advisory committee of outside experts. In an attempt to add more rigor to the agency’s decision-making process, he said this week that the FDA intended to issue new guidance on the standards used to justify emergency use of a vaccine.

“We will not jeopardize the public’s trust in our science-based, independent review of these or any vaccines,” Hahn said on Twitter on Friday. “There’s too much at stake.”

The administration has come under withering criticism for not acting aggressively enough to confront the virus and failing, for example, to push through bureaucratic red tape in the pandemic’s early stages to develop diagnostic tests that would work. White House officials say the president is now doing exactly what his opponents have assailed him for not doing: exerting pressure to develop safe and effective drugs and vaccines as quickly as possible because people are sick and dying, not because of the timing of the election.

The rushed plasma approval rollout is far from the only aspect of the government response to the virus that was shaped by pressure from the White House. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has repeatedly waffled on how much testing is recommended and for whom, and according to emails first reported on Friday by Politico, political appointees at the Department of Health and Human Services have tried to revise or delay CDC reports on the coronavirus they believed were unflattering to the president. The FDA first gave emergency authorization for use of hydroxychloroquine to treat COVID-19 after Trump promoted it, only to be forced to reverse itself.

But the battle over approval of convalescent plasma is particularly telling because it involves many of the players who would figure in a far more momentous decision over whether to authorize an emergency approval for a vaccine.

Over the summer, the debate over plasma evolved from a purely scientific discussion about its merits to a kind of political loyalty test, laid bare in presidential remarks in the days before the announcement.

In a news briefing on Aug. 19, Trump complained that “people over there” — an apparent reference to the FDA — wanted to limit plasma treatment until after the election. In a Twitter post three days later, he accused “deep state” officials at the agency of slow-walking approvals of COVID-19 vaccines and treatments to harm him politically.

Like other approaches to dealing with the virus, convalescent plasma was a subject of scientific debate and disagreement. The pale yellow liquid that remains after blood is stripped of its red and white cells has been used since the 1890s to treat infectious diseases, including the flu, severe acute respiratory syndrome (or SARS) and Ebola.

Regulators at the FDA, which approves new treatments, were willing to evaluate convalescent plasma for emergency approval on the basis of tens of thousands of case studies from a federally supported Mayo Clinic program. Collins and other officials at the NIH wanted its benefits tested with randomized trials, for which scientists across the country had struggled to recruit patients. Although NIH did not have regulatory authority, the administration wanted agreement among all the health agencies on moving ahead with expanded use of plasma.

In June, Marks alerted Dr. Deborah Birx, the White House coronavirus response coordinator, that early data from the Mayo Clinic program looked promising. Mark Meadows, the White House chief of staff, quickly began agitating for emergency approval, senior administration officials said.

Throughout the summer, the White House has kept a close eye on the FDA’s progress with therapies and possible vaccines. The president himself calls Hahn on his cellphone about once a week, according to a senior administration official.

Meadows is also in regular contact with Hahn, who sometimes makes unscheduled visits to Meadows’ corner suite in the West Wing.

Dr. John Fleming, a top adviser to Meadows, holds a weekly meeting with Hahn, Marks, Dr. Janet Woodcock, a top FDA drug official, and Eric Hargan, the deputy health secretary. Jared Kushner, the president’s senior adviser and son-in-law, was also closely involved in tracking progress on vaccines and treatments.

For weeks, FDA regulators, backed by Hahn, insisted the data from the plasma research was not strong enough to justify approving wider use. By Aug. 12, though, they were ready to move ahead, deciding plasma met the comparatively low bar for emergency authorization in which the potential benefits outweighed the risks.

NIH officials were still arguing for a clinical trial, but the scientists arrived at a compromise: The FDA would analyze the data again with fresh results from the Mayo Clinic program.

Frustrated by the delay, Trump pressed his case with Alex Azar, his health secretary.

Two allies of Kushner’s got involved: Brad Smith, a deputy assistant to the president, and Adam Boehler, the chief executive of the U.S. International Development Finance Corp. and a former Trump administration health official.

They talked to Hahn and Azar about data that they said showed that plasma from the Mayo Clinic program was available to only three-fourths of the hospitals treating COVID-19 patients, leaving 900 hospitals without access to the therapy. While emergency approval was held up, they noted, Americans were dying.

Matters came to a head on Aug. 19 after The New York Times published an article saying the plasma approval was on hold because of the NIH objections. FDA and White House officials were furious that NIH officials had publicly aired their objections despite negotiations to resolve the conflict over data. Trump called Collins demanding that plasma be approved within two days.

Birx and other top health officials also lashed out at Collins, asking him to publicly clarify his position, according to senior administration officials with knowledge of one tense meeting that week.

At the FDA, officials were expecting to finish the new analysis for the NIH and to announce emergency approval of plasma as early as Monday, Aug. 24.

But on the preceding Thursday, they were told that was too late: The decision had to be announced on Sunday, the day before the start of the Republican National Convention, ostensibly because making the announcement during the gathering would appear to be politically driven.

Another obstacle emerged that weekend: New Mayo Clinic data was missing key entries and could not be used, foiling the reanalysis.

White House officials said they were told by Azar and Hahn that they were ready to make the announcement on Sunday. The president’s communications team quickly put together an event in the White House briefing room, with Trump flanked by Hahn and Azar. The FDA called the approval “another achievement” in the administration’s battle against the pandemic.

The rush contributed to serious mistakes. Hahn misinterpreted agency data and claimed that plasma reduced the mortality rate of COVID-19 patients by 35% — a substantial exaggeration of what the research actually showed.

Immediately after the announcement, however, the mood in the Oval Office was celebratory. Cupcakes were served. Photographs were taken.

Before him on the Resolute Desk, the president had multiple copies of that day’s Wall Street Journal. He noted with pleasure a prominent article stating that he had forever changed the Republican Party.